- Share via

In a city that loves rags-to-riches stories, few can match the saga of Pepe Aguilar and his family.

But only some Angelenos know about it.

His father, Antonio, slept on benches in Placita Olvera when he arrived in Los Angeles from Mexico in the 1940s with no papers but plenty of ambition. He triumphantly returned in the 1960s as a ranchera legend, with an espectáculo featuring his family that brought Mexico back to homesick immigrant L.A. audiences, if only for three hours.

These extravaganzas, which interspersed music with rodeo events, evoked the rural traditions of Jalisco and Zacatecas, from where hundreds of thousands of Mexican Americans in the Southland trace their roots; what might’ve seemed like a circus act to non-Latinos was really an authentic, if romanticized, portrayal of culture of these Mexican states.

The Aguilar family toured from New York City to Puerto Rico to Idaho but found their most devoted fans in L.A., where Mexican Americans saw themselves in the U.S.-born Pepe, who adopted his father’s stage act and expanded it into his own.

Fans saw him grow up on stage, from a 1-year-old strapped onto a horse and billed as “Pepito,” to a 6-foot-5, bilingual, Paul Bunyan-esque ranchera superstar who loves the prog-rock gods Rush, maintains a lively Instagram feed, and whose family has performed so much across Southern California that he jokes “we’re becoming part of the scenery, man.”

Born Jose Antonio, but universally called Pepe, the 51-year-old’s story is that of his fans: a Los Angeles that has transformed from a city where Mexican Americans were a minority to one where they’re now almost half of the population.

Yet still, in many ways, invisible. In vast parts of L.A., the Aguilars’ story doesn’t register one blip.

Non-Latino workers at Staples Center looked on in bemusement in June at the arrival of Jaripeo Sin Fronteras (Rodeo Without Borders), Pepe’s update of his family’s road show, now also starring his brother, Antonio Aguilar Jr.; a son, Leonardo; and a daughter, Ángela.

As workers backed up livestock trailers and unloaded angry bulls onto loading docks more accustomed to hosting NBA charter buses, a security guard summed up the spectacle as “some sort of Mexican cowboy thing.”

Meanwhile, in a nearby room, Pepe held court.

“Hello, hello, ¿cómo estamos?” he said to three dozen fans — men and women, young and old, Spanish- and English- and bilingual speakers. He wore a military-style jacket, huge Linda Farrow sunglasses, jeans, a black bucket hat and boots with spurs.

Pepe bantered with devotees as they approached for a photo. Some laughed. Some cried. Some sauntered up with macho swagger. One woman shook nervously and stared.

“Am I dreaming?” she finally said in Spanish.

Pepe’s proud, positive expression of mexicanidad that looks to the past as he barrels into the future may seem an exercise in nostalgia to outsiders. But to Latinos in an era of deportations and xenophobia, Pepe’s career has become a reminder of the power of knowing your roots — and a challenge for others to do the same.

“You don’t have to become a folkloric mariachi singer to honor your background,” Pepe said. “But just knowing where you are in history and what your ancestors were will make you stronger. I’m a true believer of that. It works for me.”

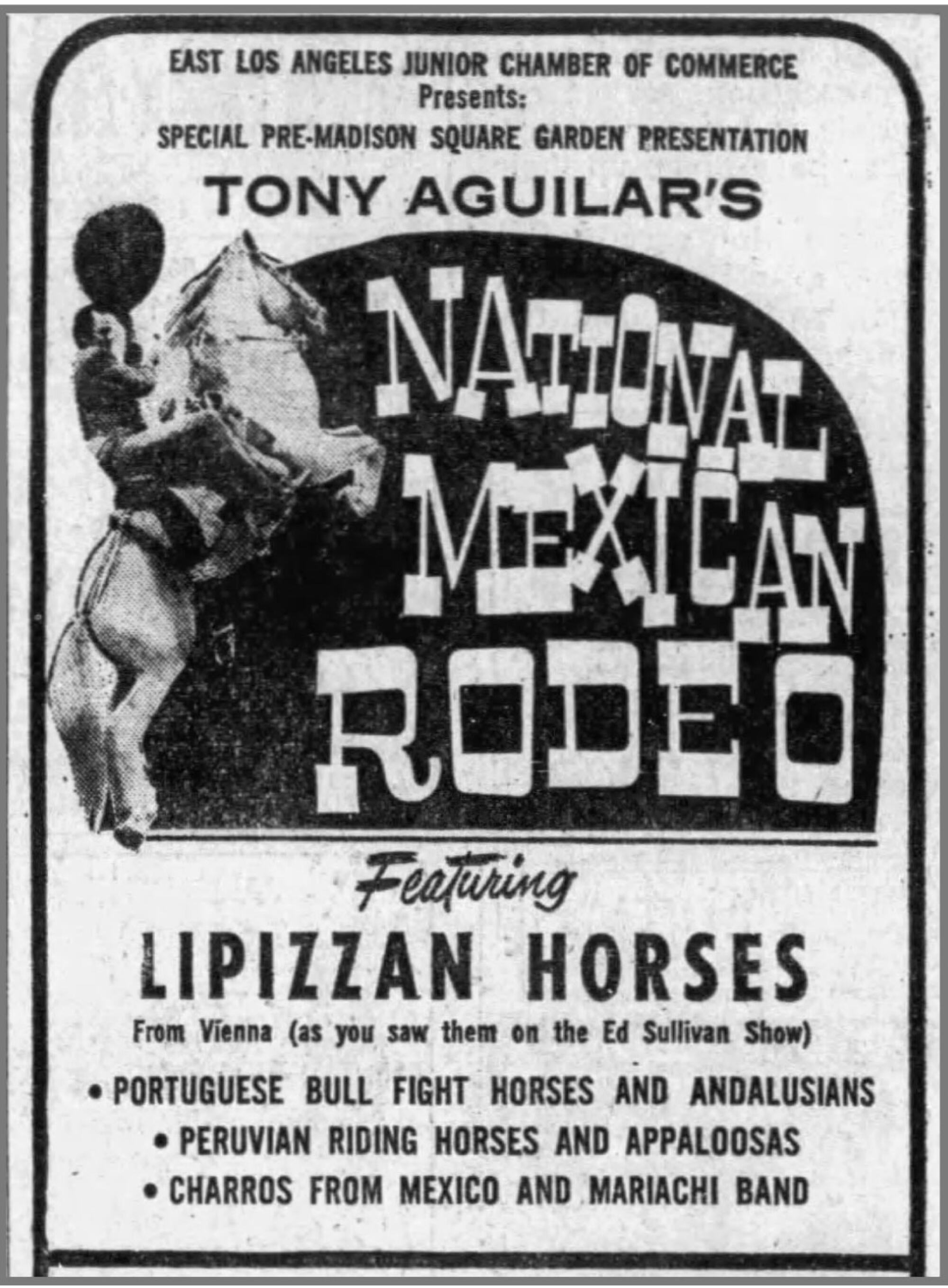

The basics of Aguilar revues have remained unchanged since the days Antonio marketed them as “Tony Aguilar’s National Mexican Rodeo.” It opens with a trick rider — in this case, Madison MacDonald-Thomas, a Canadian — storming into the arena waving Mexican and American flags. Horses prance to the thundering beats of banda sinaloense.

But there are modern touches too. Video screens flash Pepe-penned slogans — “The bigger borders are that which are constructed in our mind,” reads one — that crowds applaud with glee. American and Mexican bull-riding teams face off against each other, with hard rock, like Guns N’ Roses’ “Welcome to the Jungle,” as a soundtrack.

Souvenir stands sell a T-shirt that reads “Primero Soy Mexicanx” (I’m Mexicanx First), a riff on debates among Latinos to create a gender-neutral term for themselves.

Pepe, meanwhile, roams around the arena on horseback or on foot, singing not just his hits — “Por Mujeres Como Tú,” “Recuérdame Bonito” — but selections from the canon of his father, and those of Juan Gabriel, Joan Sebastian and L.A. alt-Latino group La Santa Cecilia.

The wholesome nature of the show — there’s enough corny banter between Pepe and his family to pat out a tortilla — is not as hip as the output of Los Tigres del Norte or Vicente Fernández, who command larger followings and mainstream attention that has largely eluded the Aguilars.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los Angeles Times.

But no other Mexican musical act touches the binational, multigenerational gestalt at the heart of the Mexican American experience, according to Adrian Félix, an ethnic studies professor at UC Riverside who writes about transnational migration.

Félix grew up listening to the songs of Antonio and Pepe, but attended his first Aguilar production this summer, when Jaripeo Sin Fronteras sold out Oakland’s Oracle Arena.

“He started the show by saying, ‘I am an English-speaking charro from Tayahua, Zacatecas,’” Félix said, “and the crowd just went wild. That needed no translation in English or Spanish. Everyone got it and felt it.”

Born in San Antonio in 1968 while his parents were on tour, Pepe has sold more than 15 million records and won four Grammys for his music, which skews toward romantic ballads but also incorporates Mexican classics, cumbias, and even rock en español.

His success has imbued him with a sense of responsibility to defend Latinos. He was a longtime critic of the Latin Grammys for what he said was their lack of respect toward Mexican regional music. (They’re cool now, he says.) Last year, Pepe partnered with Voto Latino to register voters at his concerts. He has consistently blasted President Trump’s immigration policies.

Times archives of Antonio Aguilar

If he could speak with the president, he said, “I would ask him, ‘How does it feel to be so irresponsible?’ ” Pepe then offers a barnyard epithet to describe how much he thinks Trump cares about Mexicans.

Pepe and his father have stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame next to each other; in Olvera Street, a 10-foot-tall bronze statue of Antonio stands near the benches where he once had to sleep. Pepe is producing the second album of Leonardo, 20; 15-year-old Ángela possesses powerhouse vocals like that of her legendary abuelita, Flor Silvestre, and seamlessly transitions between Selena covers and ranchera classics.

He sees Jaripeo Sin Fronteras not just as a career culmination and showcase for his family, but as something tinged with larger meaning.

“I got to a point in my life where focusing just on me was very boring and just felt empty,” he said recently at a Burbank recording studio. Pepe was about to walk Leonardo through “El Barzón,” a famously tongue-twisting ranchera. “I was very proud of creating a challenge [with Jaripeo] that was bigger than me. To understand that the thing we’re doing is way bigger than my family.”

“There’s so much BS going on, this separation of culture that the government wants right now,” he continued. “Now, it’s very important to show our culture in a way that’s proud and true.”

Early on, non-Mexican Southern California looked on in bewilderment at the success of la dinastía Aguilar. The Los Angeles Times, in a 1966 review of a performance at a packed Million Dollar Theater, remarked on their “inexplicable drawing power.”

By then, Antonio was a superstar in Mexican film and music, but knew that his audience lived on both sides of the border. Hollywood took note. He appeared in the 1968 flick “The Undefeated” alongside John Wayne and Rock Hudson and once sang at the Hollywood Bowl on a ticket that featured Ricardo Montalban, Frank Sinatra and Dionne Warwick.

While in L.A., Antonio treated his family to the best of SoCal life. Pepe remembers trips to Disneyland and regular stops at Hollywood’s Musso & Frank Grill.

“He couldn’t afford it when he was a homeless Mexican,” Pepe said, “and he wanted to give us an experience.”

But his happiest memory was the scent of the region. “I think I’m a weirdo, because I’d smell the chlorine and rubber, and that smell means I’m in L.A.,” he said with a laugh.

Though the Aguilars maintained a ranch in Zacatecas, Pepe said he has “always looked at L.A. as a home.” He relocated to Los Angeles 13 years ago to give his family not just easier access to the entertainment industry but, more important, a “mixed multicultural experience every second, every minute on every street and restaurant.”

It doesn’t bother him that L.A. as a whole has yet to embrace los Aguilares.

“We’re not doing what we’re doing to be famous with all people,” he said. “We’re doing what we’re doing” to be boldly mexicano for his fans, in a time when it’s needed.

Pepe and his family “remain unknown because they are icons of working-class Mexican communities,” says Josh Kun, director of the USC Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism. “And the history and culture of those communities — tied to deep traditions of cross-border immigration — have always been relatively invisible to greater L.A.”

But another L.A. does know the Aguilars, and that L.A. defies stereotype. Fans come dressed in Chanel finery, gleaming guayaberas, or Stetsons color-coordinated with cinto piteados — leather belts stitched with arabesque designs. They’re fashion tree rings that speak to different epochs of the Southern California Mexican experience.

El Sereno resident Gilberto Murillo, 69, went to the June jaripeo with his wife, their daughter, her boyfriend, his pouting, geeky brother and their parents. He remembers seeing Pepe as a young boy singing on horseback alongside his parents.

“They’re a family that look like us,” Murillo said in Spanish. “Hard-working. Proud. Close. Successful.”

“He shows everyone how a real Mexican is — puro honor,” said 23-year-old Erasmo Gutierrez of Fontana, who could only afford nosebleed seats and came by himself.

A reporter finds that the Aguilar family’s story is much like his own

“Every show is different, but he’s always 100% class,” says Cynthia Ascencio, 43, of Queen Creek, Ariz. “With everything that’s going on right now, that means a lot.”

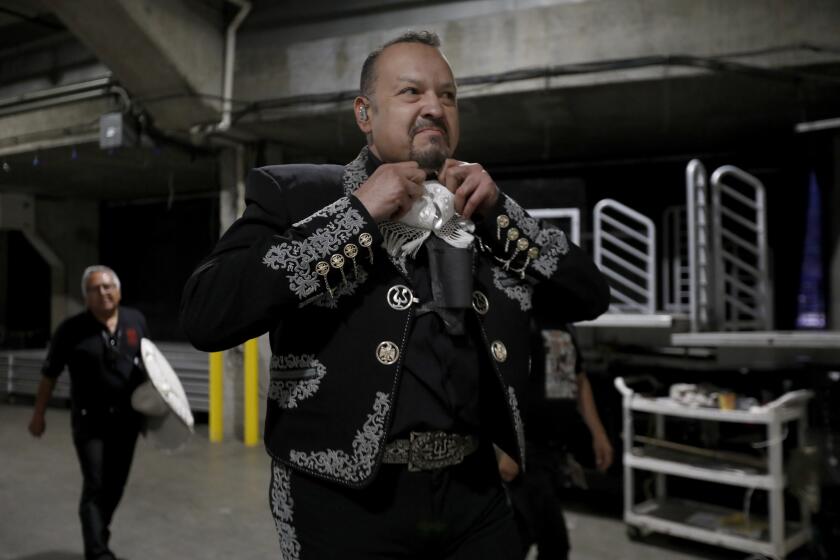

Before Pepe made his entrance at Staples Center, he reflected on his family’s legacy. He had just strode through the bowels of the arena, down the walkway that has hosted Kobe, Shaq and LeBron. Dressed in boots, spurs, an intricately embroidered black charro suit and a fabulous sombrero, Aguilar towered over ecstatic, photo-snapping janitors as he finally stopped in front of an Andalusian horse with the image of an Aztec eagle warrior shaved onto its haunches.

But before mounting his steed, El Caporal, Aguilar rattled off just some of the Southern California venues where his family has played: The Pantages, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Walt Disney Concert Hall, Dodger Stadium, Anaheim Convention Center, Pico Rivera Sports Arena.

“Traditions have to start somewhere,” Aguilar said as the crowd roared in anticipation of his entrance. “They didn’t just appear from nowhere.”

He shook his head like a boxer, got on El Caporal, and galloped off to his L.A.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.