- Share via

It was the meal that changed how Angelenos eat.

And it happened more than 5,000 miles from Los Angeles.

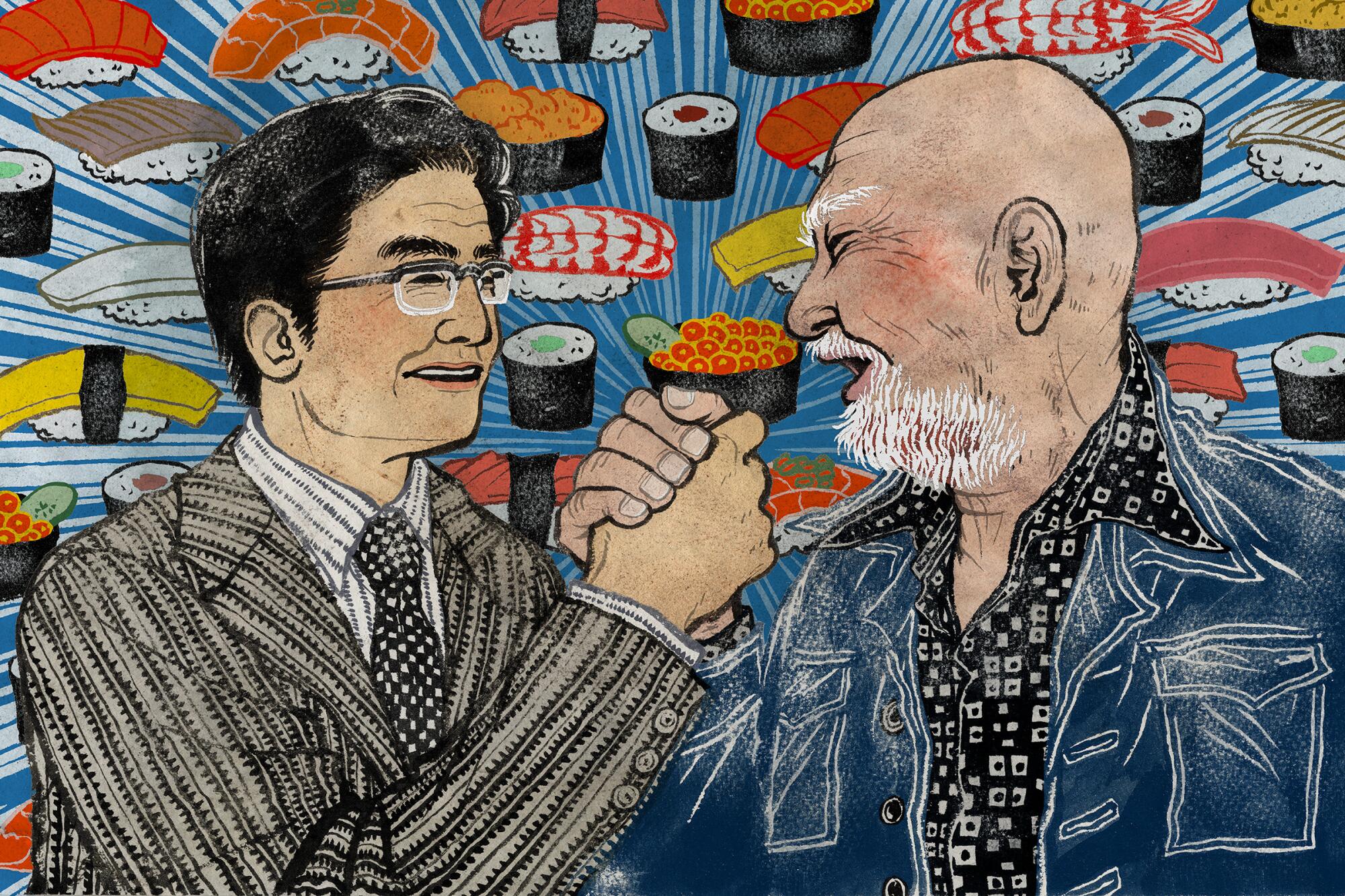

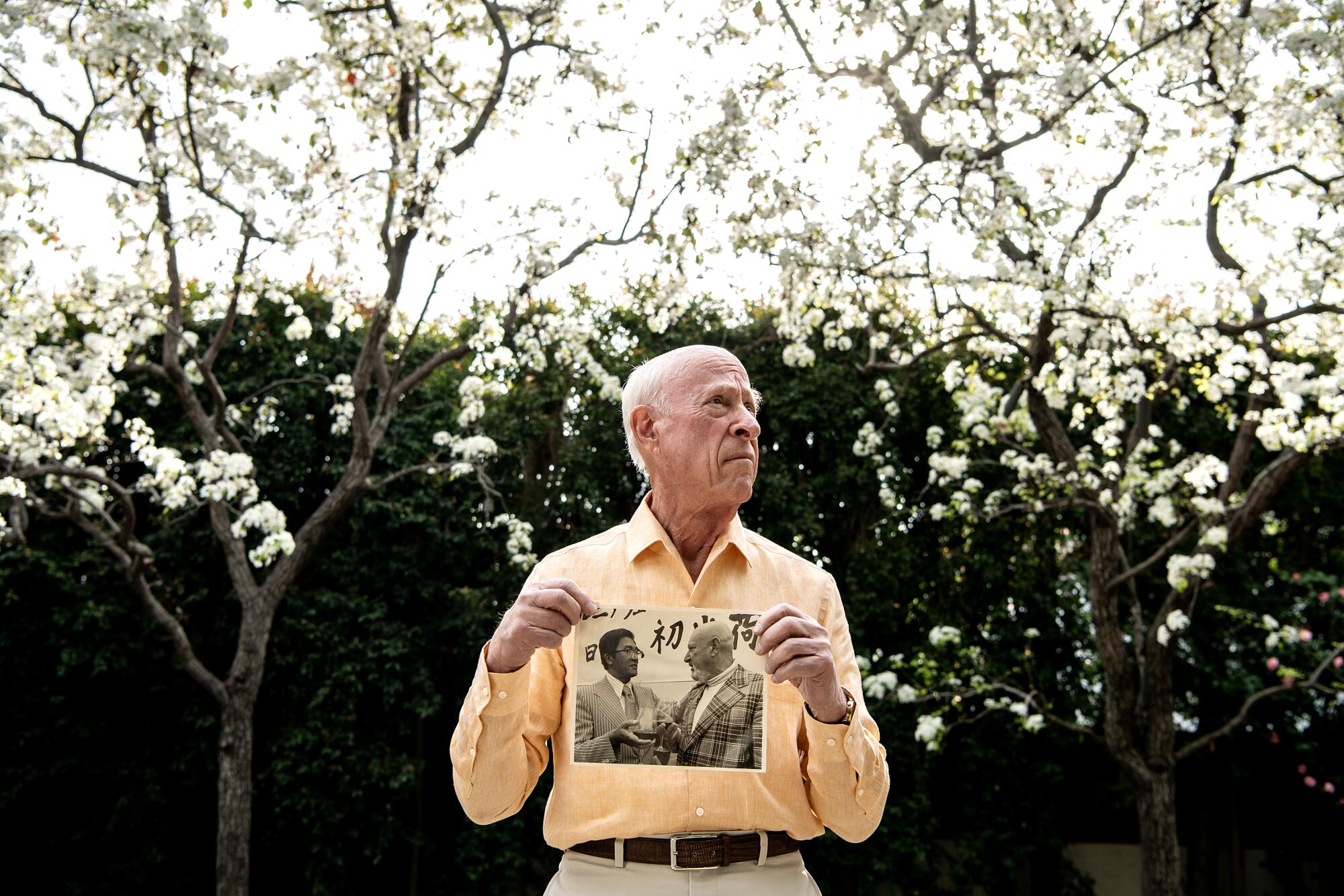

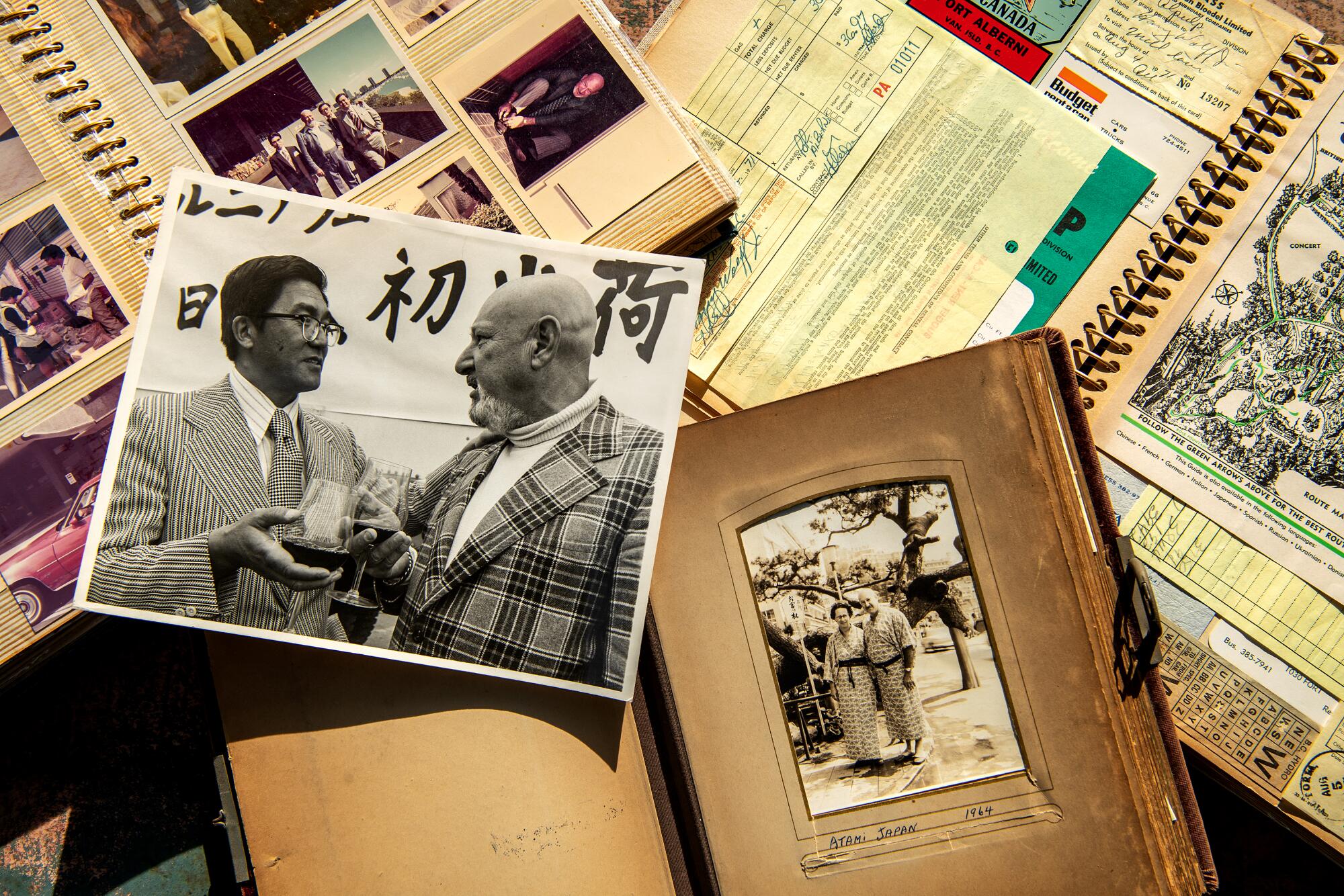

When Noritoshi Kanai and Harry Wolff Jr. sat down for dinner in Tokyo one night in 1965, they had no way of knowing they were about to stumble onto an idea that would upend American dining — and their own lives.

On this evening, the colleagues had more urgent concerns on their minds: how to salvage a foundering trip in Asia that was launched to find a novel food product to import to the U.S.

That item, it turns out, was actually on the menu.

Sushi.

From vegan sushi to hand rolls, modest supermarket sushi to high-end omakase — the greater-than-ever scene in L.A. has what you’re looking for.

Kanai, who managed Mutual Trading Co., an L.A. wholesaler of Japanese food products, had suggested the restaurant, a family-run spot in the Ginza district called Shinnosuke. Wolff had never eaten sushi, but Kanai figured he’d be game.

“He’d try anything,” Kanai recalled, laughing.

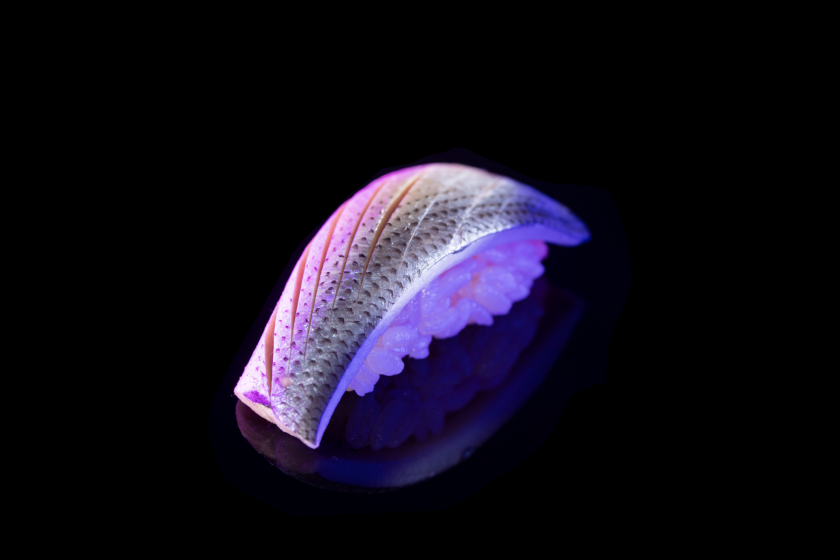

Before long, Shinnosuke’s sushi chef was turning out a cascade of nigiri.

Tuna. Octopus. Cuttlefish. Scallop. Sea bream.

Wolff ate with enthusiasm. But the significance of the meal wouldn’t become apparent until five days later.

That’s when the restaurant sent a bill to Kanai’s Tokyo office — for about $275, which, when adjusted for inflation, is about $2,650 today. It was, Kanai said, a shockingly large sum. “What happened?” he asked his associate.

Wolff explained that he had been slipping away to feast on sushi at Shinnosuke. And he wasn’t just eating — he was imagining how to bring sushi to L.A. restaurants.

Kanai recalled Wolff’s earnest entreaty: “Kanai, go do sushi. Sushi is good.”

It was a bold proposition.

At the time, Los Angeles’ culinary landscape was lackluster. French cuisine dominated fine dining, and drab Continental cooking could be found at restaurants across the city. Casual diners ordered meatloaf and burgers at the local greasy spoon.

“Asian food just wasn’t part of that conversation,” said Nancy Matsumoto, an expert on Japanese food and co-author of “Exploring the World of Japanese Craft Sake.” “The world view was the Westernized world view.”

Cultural cuisines often were presented as watered-down approximations. The city’s Japanese restaurants — Kawafuku in Little Tokyo and Yamashiro in Hollywood among them — were known for specializing in items such as sukiyaki, a beef dish calibrated for Americans’ sugar-craving tastes.

Kanai, go do sushi. Sushi is good.

— Harry Wolff Jr., Noritoshi Kanai’s business associate

If sushi could find purchase on the menus of L.A.’s Japanese restaurants, Kanai’s company, already adept at importing cookies and other products from Japan, stood to reap the benefits.

An ambitious plan soon took shape. Mutual Trading would import the ingredients and implements needed to serve sushi here — from the nori to the knives. And it would source other items such as sea urchin locally.

The aim, in essence, was to create a sushi ecosystem for Los Angeles. Would it work?

The glittering omakase bars of Beverly Hills, the hipster hand-roll spots of downtown L.A. and the strip-mall gems of Ventura Boulevard would seem to answer that question.

L.A.’s sushi revolution began in the 1960s at Kawafuku, a grand Little Tokyo restaurant whose story is one of glamour, heartbreak and innovation.

Kanai and Wolff forged a path for other entrepreneurs, including Nobu Matsuhisa, who opened L.A.’s Matsuhisa in 1987 and parlayed that hit into a chain of Nobu restaurants and high-end hotels scattered around the world.

With their success, Wolff and Kanai became the ultimate odd couple — one an imposing Jewish man who’d cut his teeth as a bouncer at nightspots in his native Chicago, the other a trim Japanese man who’d served as a quartermaster in the Japanese army during World War II.

The men had been bound by a love for food — and a dream of uniting disparate peoples, according to Kanai’s daughter, Atsuko Kanai. The friends saw a model for finding common ground in their own relationship. Wolff, she said, must’ve perceived “the similarities between the Japanese and the Jewish cultures and beliefs,” adding, “They were very curious to learn from each other.”

The two families grew close: One year, they all gathered for Passover, the Jewish holiday commemorating the biblical story of Exodus. Kanai showed up for the Seder at Wolff’s house with a platter of — what else? — sushi, relatives recalled.

Their business triumph, however, came at a cost. By the time Kanai sat for an expansive interview with The Times in 2015 at Mutual Trading’s then-headquarters near Little Tokyo, he and Wolff had long since parted ways.

The current generation of omakase chefs in Los Angeles are returning to the essence of the cuisine. A trip to Tokyo confirms what’s been driving their pursuit for excellence.

Kanai, then 92, knew Wolff had died many years earlier but had few details. He had tried to track down his former collaborator’s kin, enlisting his daughter in the unsuccessful effort.

“He’s been looking for Mr. Wolff’s family forever,” Atsuko said in 2015.

They’d once been L.A.’s renegades of raw fish. Now they were something else entirely.

Los Angeles is home to eight Michelin-starred sushi restaurants — and countless other spots — that treat raw fish with the sort of reverence usually reserved for religious rites. It’s also known for places with a Mad Hatter flair for incorporating the fare into decidedly baroque concoctions such as the sushi burrito or cheeseburger sushi.

Those items are a far cry from the ancient Japanese dish of fermented fish that, over the centuries, morphed into nigiri, typically a piece of raw seafood draped over an oval of rice. According to University of Kansas professor and sushi expert Eric Rath, nigiri was popularized in Tokyo in the early 1800s, when the fish could be raw, marinated or cooked — and it was seasonal by default.

Sushi was, of course, known to Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans in L.A. well before the efforts of Wolff and Kanai, but it was typically simple and homespun. Among the items frequently served in Japanese American homes, Matsumoto said, were inari sushi, a fried tofu pocket stuffed with rice; and futomaki sushi, a thick roll usually filled with vegetables and sometimes cooked seafood.

Sushi was first mentioned by The Times in an 1899 article penned by “a Japanese contributor” who referenced a bento box that included it. In the intervening decades, a handful of L.A. restaurants included sushi on their menus — in the form of inari or similar items. Kanai noticed the availability of those offerings in Little Tokyo when he first visited L.A. in 1956. But he wrote in his 1996 Japanese-language autobiography that “there was nothing close to … Tokyo-style nigiri sushi.”

Soon, that would change.

“In retrospect, it was a brilliant business plan,” said food historian Samuel Yamashita, a Pomona College professor. “One could argue the Kanai-Wolff collaboration fed into the elevation of Japanese cuisine from an ethnic to a haute cuisine.”

Wolff and Kanai met by chance on the floor of a Chicago trade show around 1964. As Kanai put it in his autobiography, a bald man who “looked like a beefy Buddhist monk” yelled at him from across the hall: “Hey, are you Japanese?”

Wolff all but clinched their business pact — he would consult for Mutual Trading, helping it distribute new products — with a piece of wry advice he gave Kanai: “In the United States, find one good doctor and a good lawyer — and also a good Jewish friend.”

Born in 1913 in Chicago, Wolff came of age during the Great Depression. He had wanted to play college football, but the financial cataclysm made it impossible. Then his mother died. Wolff was 19, and he needed to help support his family.

Wolff took a job shoveling coal at a department store — for about $10 a day. That, his son Martin Wolff said, was “a lot” in those days. Wolff had a side hustle too: bouncing at venues ranging from fancy restaurants to gambling dens, relatives said. “He was there to make sure everybody was straight,” Martin said.

Above all, Wolff could sell. In 1946, he moved his family to Washington, D.C., where he took a job at Kay Jewelers. At the time, it sold a variety of goods, including televisions, a newfangled invention he learned to exploit. It was, according to Martin, his father’s idea to set up TVs in the company’s stores and screen the popular “Milton Berle Show.”

“People mobbed” Kay Jewelers’ shops, Martin said. “And then they … [bought] all these different products, including televisions. He knew what people wanted.”

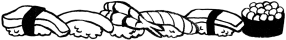

By the early 1960s, Wolff lived in Brentwood with his family. His circle of friends included Richard Nixon, whom he met while trying to arrange a gubernatorial debate between the former vice president and Gov. Pat Brown ahead of the 1962 election. Nixon lost but stayed in touch.

“When Nixon was elected president, he asked my dad to come in — because he wanted to get a job for him in the White House,” Martin Wolff said. “My father turned it down. He said, ‘You know, I’d love to do it.’ But he said, ‘I can’t do it because my first grandchild was just born. I wouldn’t miss these things for the world.’”

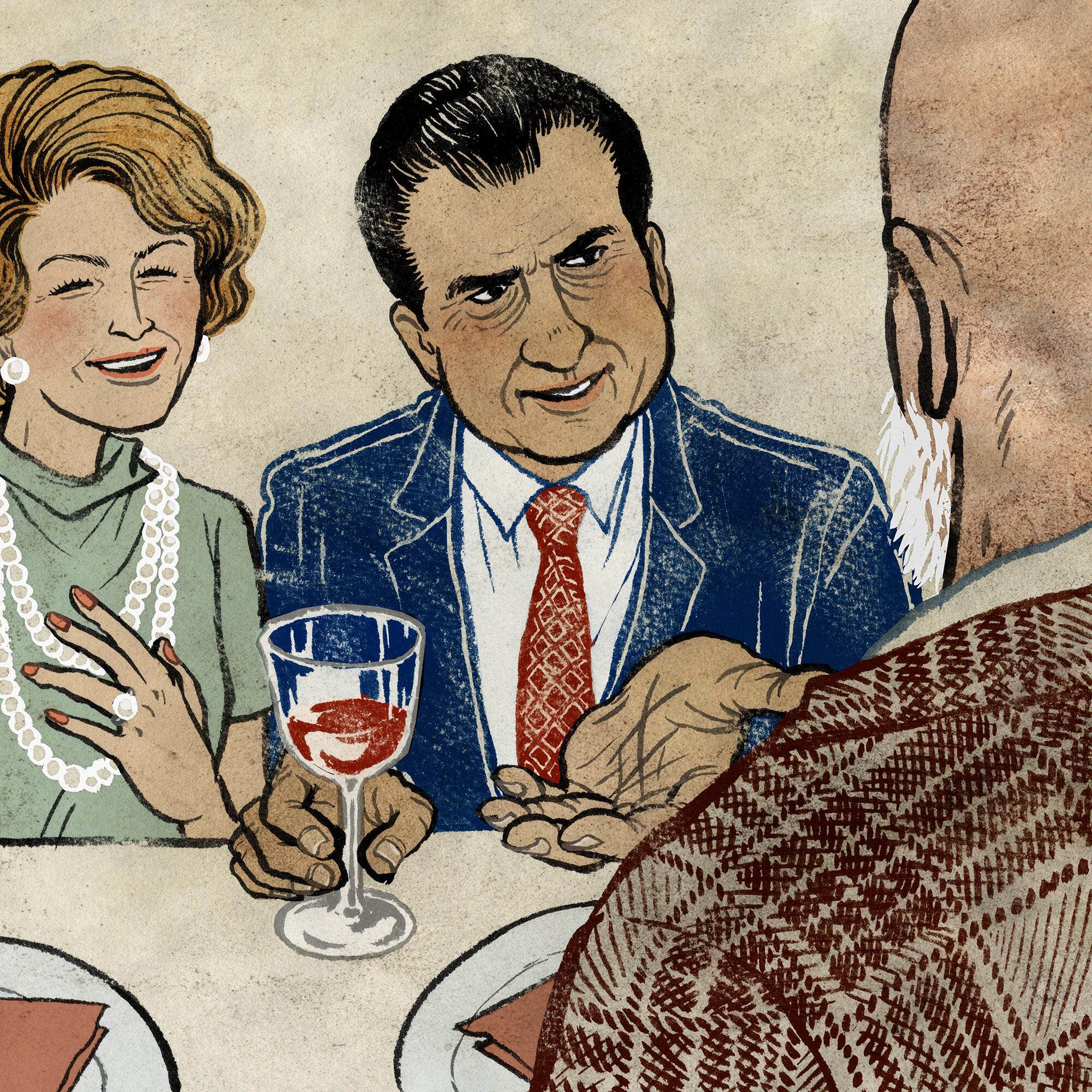

Kanai was born in 1923 and grew up in Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward. He had a comfortable upbringing, but the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor ensured Kanai would be pressed into military service. Four years later, he found himself in occupied Burma, where he served in the Japanese army as a quartermaster, responsible for providing rations and supplies.

“I was 20 years old — very young, like a child,” Kanai said. “Instantly, the world changed. Always, I am afraid of losing [my] life.”

Tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers died during Japan’s occupation of Burma, many from malnutrition. There was never enough food; at one point, Kanai wrote in his autobiography, he subsisted partly on potatoes he dug out of the ground.

“What I once thought was the indestructible Japanese army organization was crumbling before my eyes,” he wrote in the autobiography, whose unpublished English translation was provided to The Times by Atsuko.

Living in Tokyo after the war, Kanai tried his hand at a number of businesses. Then, in 1951, he joined Tokyo Mutual Trading Co., which was affiliated with L.A.’s Mutual Trading. He made his first trip to the Southland five years later. Kanai was dazzled by the region’s postwar prosperity and permanently relocated to L.A. in 1964 to manage Mutual Trading.

One of his early successes involved importing Harvest sesame cookies. But it didn’t last. Similar treats flooded the market, sapping his sales. Kanai came to realize he needed items that couldn’t be easily imitated.

“The way to get in,” he wrote, “was through products that the Americans didn’t know about or understand. Authentic Japanese food would not be easy to copy.”

He knew what he needed: a trip to Asia. With Wolff.

There are different versions of the story of the sushi dinner at Shinnosuke and its aftermath. Passed down through the Kanai and Wolff families, each emphasizes a slightly different element of the drama, a slightly different lesson learned.

But in all the accounts one thing is clear: Kanai didn’t buy Wolff’s premise that sushi would be the next big thing. He needed convincing.

Wolff delivered a pitch that started by contrasting sushi with L.A.’s prevailing fine-dining fare. According to Atsuko, Wolff’s spiel went something like this: “French chefs are so snobby — they have these tall hats, and the higher they are, the more aloof they are, and it’s no fun. But the sushi chefs, they’re your friend. It’s entertainment.”

“No, Americans don’t eat raw fish!” Kanai shot back, according to his daughter.

Before Koda Farms debuted a new strain of rice that would fuel the sushi boom, the family behind it lost nearly everything during World War II.

In Martin Wolff’s telling, his father replied with a blunt assessment of Angelenos’ hoped-for embrace of sushi: “Believe me, they’ll eat it. If I eat it, they’ll eat it.”

Then, according to Atsuko, Wolff reminded Kanai about the lesson learned with Harvest cookies. “If you take sushi to the United States, who’s going to copy you?” he asked Kanai.

Wolff had won him over.

Their timing was impeccable. In the 1950s and ’60s, Rath said, three innovations made it much easier to import products from Japan: refrigerated shipping containers, regular and direct transpacific flights, and the globalization of Japan’s fishing fleet.

There was also a new development in California: the invention of a special strain of medium-grain rice at Koda Farms in the Central Valley. Released in 1962, it had been created at the behest of owner Keisaburo Koda, a Japanese immigrant who wanted to provide his customers with a higher-quality product — one that was similar to what was readily available in Japan. The rice was perfect for sushi in part because it didn’t become brittle as it cooled.

Still, for the businessmen’s plan to work, restaurants needed to be willing to give sushi a shot. With most Japanese eateries in L.A. catering to Western tastes, few had any reason to take a risk. But there was one spot in Little Tokyo — Kawafuku — that had an outsize influence on local Japanese cuisine. Since its opening in 1923, it had been a favorite of stars, sportsmen and statesmen alike.

Charlie Chaplin dined there. Boxing champion Hiroyuki Ebihara visited. So had the onetime commander in chief of the Japanese imperial fleet.

If the owner could be persuaded to open a sushi bar on site, it might offer the foothold Mutual Trading needed.

At first, Kanai’s pitch failed to resonate.

“No, no, no — we will be run out of business,” Kawafuku owner Tokijiro Nakashima told Kanai when he broached the topic of serving sushi at the restaurant, according to Atsuko.

Nakashima had acquired Kawafuku in the mid-1940s from its founder, a former chef at Japan’s Imperial Palace. The restaurant, whose lavish interior boasted a koi-stocked stream, was already beloved.

Over the next six months, Kanai repeatedly appealed to Nakashima without success. Eventually, his wife intervened. “Let’s trust this guy — let’s try it and see if it goes,” she told her husband, according to Atsuko.

The owner of the Joint talks seafood, preservation and a sprawling new facility that will bring dry-aged fish to the masses.

After Nakashima agreed, Kanai gave him the name of a carpenter who would reconfigure part of the restaurant so sushi could be served there. It needed to be a special space. Kanai dubbed it a “sushi bar,” according to Anthony Al-Jamie, editor in chief of Tokyo Journal.

Kawafuku’s sushi bar opened around 1965, and as it gained a following, other eateries in Little Tokyo, including Eigiku Cafe and Tokyo Kaikan, added their own.

The spread of sushi beyond Little Tokyo was ignited by the 1969 opening of O-Sho Sushi on Pico Boulevard near the 20th Century Fox studio. And Mutual Trading supplied the West L.A. establishment with the items needed to serve sushi, Atsuko said. Among its patrons was actor Yul Brynner, who became something of an evangelist for the cuisine, promoting it to others in his circle.

Believe me, they’ll eat it. If I eat it, they’ll eat it.

— Harry Wolff Jr., Noritoshi Kanai’s business associate

Brynner’s efforts helped propel sushi into the zeitgeist; it eventually would appear in countless films and television shows, including “The Breakfast Club” and “Seinfeld.” American consumers’ interest in all things Japanese — including the cuisine — also was influenced by “Shogun,” a hit TV miniseries based on James Clavell’s bestselling novel of the same name. Centered on an Englishman who became a Japanese lord, “Shogun” contributed to an overall “fascination with Japanese culture,” said Rath, author of the sushi history “Oishii.”

Untethered from conventions followed in Japan, sushi chefs in L.A. began to innovate. One proprietor used a plastic dish in the shape of a boat to plate a sushi spread for two people. The popular offering, according to Kanai, was dubbed the “love boat.”

“Things that would have been considered heresy in Japan went over quite well in Los Angeles,” he wrote.

The same might apply to the California roll, which is said to have been invented at Tokyo Kaikan by chef Ichiro Mashita. (There is a competing claim, though histories including “The Sushi Economy” give credit to Mashita.) Kanai wrote that the roll was born out of “desperation.” Needing a replacement for tuna, whose seasonal supply “would sometimes dry up,” Mashita turned to avocado. He believed the oily fruit could approximate the texture of toro, a fatty cut of the fish.

The California roll was first mentioned by The Times in a 1979 review of Niikura in Tarzana. The eatery was on Ventura Boulevard, making it a progenitor of the strip-mall spots that now dot the Valley’s main artery. Indeed, by the time of the review, sushi had spread far beyond Little Tokyo. It wasn’t necessarily the epicenter for the cuisine any longer. Even Kawafuku had left the neighborhood, moving to Gardena in 1976.

Though data are hard to come by that would show the growth of sushi — several food industry resources said no such figures exist — Kanai shared a few in his autobiography. He wrote that the number of sushi restaurants in Southern California increased 197% from 39 to 116 over the four-year period that ended in 1980.

The ’80s saw the cuisine ascend another level, with institutions such as Sushi Nozawa opening during the decade. Sushi was everywhere.

For Wolff and Kanai, things were changing too.

Though not an employee at Mutual Trading, Wolff was an indispensable advisor.

Kanai marveled at his negotiating skills. Sometimes, Kanai wrote, Wolff would square up against opponents at the bargaining table and “lash into them with all he had.” But it was just a tactic — what Kanai called a “put-on.”

When Kanai took on Wolff as a consultant, they made a deal: Wolff would receive a commission that amounted to a percentage of the sales his efforts generated for Mutual Trading, Kanai wrote. The agreement covered Wolff helping Mutual Trading distribute cookies and crackers, according to Kanai’s autobiography. The description of the arrangement made no mention of sushi.

According to Martin, Kanai eventually sought to renegotiate the pact and pay Wolff a smaller share. Wolff wasn’t having it.

“He said, ‘You know what … you can find somebody else, I’m going,’” Martin said of his father. “And that was it.”

It was an abrupt end to a years-long relationship.

“My father was like that,” Martin said. “If Kanai at that time said, ‘Well, OK, maybe we’ll change’ — that would have done it. But they never spoke again.”

Atsuko said her father never mentioned the dispute. And neither Wolff nor Kanai appear to have left any record of it.

In his later years, Wolff earned public notice for voyages he’d enjoyed with his wife, Virginia, aboard commercial freighters. On those oceanic journeys, Wolff took to writing messages in bottles and throwing them overboard. A 1991 Times story said that he had received more than a dozen replies from people across the globe.

Kanai had reason to be proud as well. In 1985, he was part of a delegation that met Japanese Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro at the Century Plaza Hotel. Then, Kanai attended a fundraiser at the Century City hotel benefiting the Republican Party. Kanai wrote that the $1,000-a-plate dinner spotlighted sushi.

“Sushi … had arrived at the point where it could top off a luxury event attended by the cream of American high society,” he wrote. “This was completely thrilling.”

Kanai, his daughter said, had hoped sushi could be used to bridge divides in L.A. And thanks in part to him, the food became ubiquitous.

But had it done what he’d hoped? After a wave of attacks against Asian Americans — anti-Asian hate crimes in California rose 177% in 2021 — Derek Arita, grandson of Nakashima, the Kawafuku owner, wondered whether food could really bring people together.

“Japanese food is everywhere,” Arita said. “Japanese people are practically everywhere in the U.S. But … it sometimes seems like we’re still not accepted. Even though our food is.”

And yet Matsumoto, the food writer, said the story of sushi in L.A. is one of a culture “opening its arms to another culture and embracing it.” And the friendship of Kanai and Wolff embodied that ideal.

“L.A. is an amazing city that does that to so many different cultures,” she said. “L.A. has always been forward-thinking — whether it’s new religions, whether it’s the entertainment industry. People have always been more open-minded. It’s that willingness to embrace new things.”

Awash in austere overhead lighting, Kanai sat in a small office at the headquarters of Mutual Trading just outside Little Tokyo. It was 2015, and he was giving The Times a lengthy interview.

He wore a dark blue suit, and had a shock of gray hair and a face that bore the hard-won lines of a man at the start of his 10th decade. He was chairman of Mutual Trading, and had been for some time.

Kanai had given several interviews in recent years, promoting his various projects, including a school for sushi chefs that he’d founded with Katsuya Uechi. He was prepared to tell his story, but there was something more urgent he wanted to address.

“Why do you know the name of Harry Wolff?” Kanai asked a reporter.

It was close to a plea.

“I talked about Mr. Harry Wolff many times — to many people — but nobody was interested,” he explained. “That’s a very important history.”

Wolff had been little more than a footnote in most of the published accounts of how sushi conquered L.A. But Kanai wanted to make something clear about the effort: “It’s not only mine. First, it’s his idea.”

Wolff died of a heart attack in 1996. He was 83. As far as Martin Wolff knew, the old friends never patched things up. But maybe another sort of reunion was possible?

A month later, Kanai hosted Martin for a lunch at Tamon, a restaurant on 1st Street inside Little Tokyo’s Miyako Hotel. Atsuko came with her father.

Seated around a long table, the diners exchanged pleasantries tentatively. But the conversation soon flowed, and Kanai regaled his audience with tales of his adventures with Wolff.

Their parting was not broached. No regrets were offered, no explanations given. It wasn’t necessary. Communing over a meal seemed to erase any awkwardness — if any had lingered — over the way things had ended.

There were many items on Tamon’s menu, among them tempura, ramen and, of course, sushi. There was little doubt, though, about what anyone would be eating. After placing his order, Martin said that his grandchildren loved sushi, and he delighted in treating them to it.

“That’s their great-grandfather’s legacy,” Atsuko told him. “Every time they go to a sushi bar, now they can say, ‘Oh, my great-grandpa brought it to the United States.’”

A server approached with the meal. Plates touched down on dark wood. Chopsticks flashed from paper sheaths. At least some of the items had been supplied to Tamon by Kanai’s company.

The sushi pioneer died two years later. His obituary in Rafu Shimpo, the Little Tokyo newspaper, called him a culinary ambassador who used “Japanese food as a cultural peace offering to mend the scars left by the World War II experience.” It explained that Kanai’s death was caused by complications from a stroke. He was 94.

But on that day at Tamon in 2015, he got to celebrate a singular accomplishment, one that changed how Angelenos eat.

And now it was time for lunch.

Kanai looked down at his plate. He smiled.

More to Read

Credits

Editor: Alice Short

Design Director: Taylor Le

Print Design: Nicole Vas

Photography Editors: Jerome Adamstein, Kate Kuo

Photographer: Mariah Tauger

Illustrator: Yuko Shimizu

Video Production: Cody Long, Yadira Flores

Digital Production: Ameera Butt

Copy Editing: Steve Eames, Minh Dang, Lisa Horowitz

Research: Scott Wilson

Audience Engagement: Rachel Schnalzer

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.