Column: Should the unvaccinated pay more for healthcare? That’s an easy call

- Share via

Americans have just about had it up to here with people who refuse COVID-19 vaccinations.

The signs are everywhere: More stringent vaccine mandates from governors in California and Washington. Righteous fury from healthcare workers exhausted from seemingly endless shifts on the front lines.

Warnings are proliferating about sick patients being turned away from hospitals because their emergency rooms, wards and hallways are filling up with unvaccinated COVID patients.

People who don’t vaccinate are imposing costs on the community that they’re not paying for.

— Dorit Rubinstein Reiss, UC Hastings Law School

More venues are requiring proof of vaccination before allowing patrons or visitors through their doors. News articles about vaccine refusers who see the error of their ways on their deathbeds are losing their power to elicit sympathy.

And now, there is more talk of requiring the unvaccinated to pay for the consequences of their selfish inaction.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“People who don’t vaccinate are imposing costs on the community that they’re not paying for,” says Dorit Rubinstein Reiss, an expert in vaccine policy at UC Hastings College of the Law. She equates them with environmental polluters, who are often charged for cleaning up the messes they’ve created.

“This is not a new idea or a new question,” Reiss told me. She identifies three rationales for making the unvaccinated pay — to internalize the cost of their behavior, extract retribution for creating costs to their neighbors, and deterrence, i.e., to prompt them to get vaccinated.

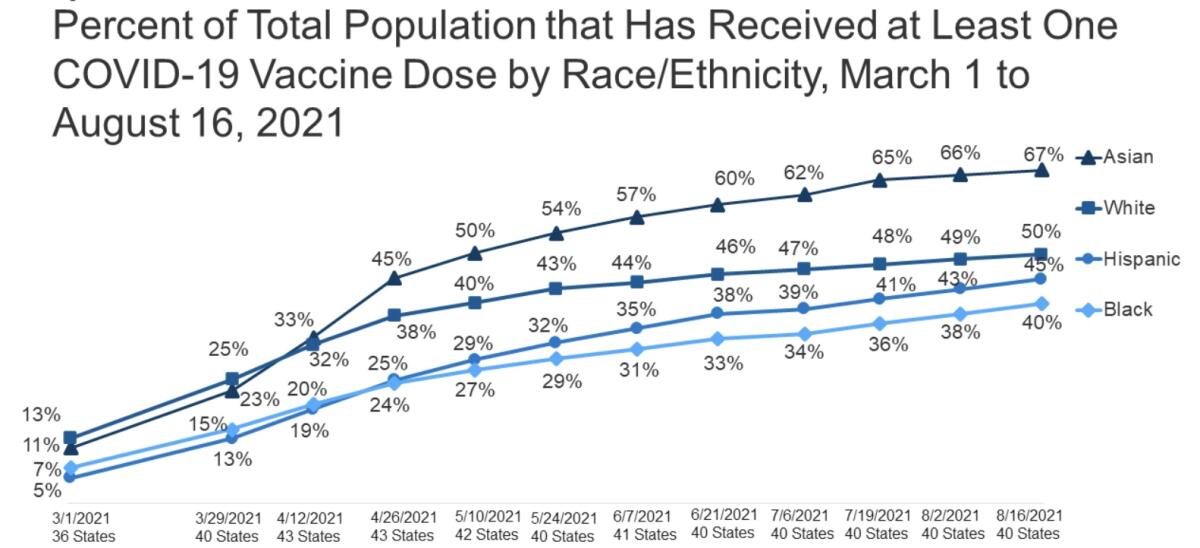

First, it’s important to define which unvaccinated Americans we’re talking about, since the unvaccinated are not a monolithic group.

There’s the cadre of Americans who can’t be vaccinated because of legitimate medical concerns, who shouldn’t be penalized for underlying health conditions.

There are pockets of vaccine skepticism in Black and Latino communities, where distrust of the government is widespread and vaccine access is wanting. Education and outreach programs must work to boost vaccination rates among these communities.

And there are adults who resist vaccines because of partisan reasons, or who have allowed themselves to fall under the sway of ideologically inspired misinformation or disinformation.

It’s hardly in doubt that vaccine refusal imposes costs on individuals and society. The unvaccinated account for the preponderance of COVID-19 patients landing in the hospital during the most recent pandemic surge in the U.S., placing a disproportionate burden on medical providers and the healthcare system, sometimes shouldering other patients out of the way.

Faced with vaccine hesitancy among players, the NFL put its foot down.

They’re more likely to become infected and more likely to become symptomatic than are the vaccinated, and therefore more likely to infect others, including children and others who can’t be vaccinated for medical reasons. They can become safe harbors for new, potentially more transmissible and deadly variants of the coronavirus, putting everyone at risk.

Government authorities have tried myriad incentives to move the country’s rate of full adult vaccination higher than the current 62%, including positive reinforcement via monetary prizes and other blandishments. It’s unclear how well they work, especially among those whose resistance is based on misinformation or partisanship.

So it’s unsurprising that advocacy for making the unvaccinated pay more directly has been appearing increasingly often in public forums. Reiss and Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s medical school, made the case in a recent article in the financial publication Barron’s.

Economist Jonathan Meer of Texas A&M University argued in MarketWatch that “insurers, led by government programs, should declare that medically able, eligible people who choose not to be vaccinated are responsible for the full financial cost of COVID-related hospitalizations.”

Meer was seconded by economist Justin Wolfers of the University of Michigan, who observed on Twitter that anti-vaxxers’ “political positions are effectively being subsidized by members of insurance pools, taxpayers, and the vaccinated.”

The increasing furor about unvaccinated Americans is plainly connected to the spread of the Delta variant, which is more infectious than earlier variants.

The manifest threat of sickness or death from COVID-19, especially as the Delta variant spreads, even trumps the cynicism of such purveyors of anti-vaccination propaganda as Fox News. There, management decreed by memo that all employees must disclose their vaccination status, to the employer, not the public, by Aug. 17.

Some New York-based employees will have to be tested at least once a week, regardless of vaccine status, and all will be required to wear masks where social distancing can’t be achieved, according to the memo. Such are the limits to the “freedom” to infect others defended so sedulously by Fox’s on-air stars. (The Times also requires employees to report their vaccination status.)

Just to repeat what everyone should know: The safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines authorized on an emergency basis by the Food and Drug Administration have been established through the experience of roughly 200 million Americans who have received at least one dose. It’s plain that, even if the vaccines aren’t 100% effective in keeping people from contracting the disease at all, they appear to be hugely successful at holding serious disease requiring hospitalization at bay.

Other than by those with certain narrow medical excuses, waiting any longer to get the shot or avoiding it altogether can’t be rationally justified.

Even as sentiment grows to require the unvaccinated to bear greater costs, the question is how to do so. That’s a tougher question.

It’s not uncommon for society to discourage unsafe behavior through legislation or regulation. People are required to shovel their sidewalks free of snow, maintain their cars so their brakes work, wear motorcycle helmets.

“These are all precautions people have to take to prevent harm to third parties,” Caplan observes.

Employers are still in the talking stage about imposing vaccination mandates on workers. That’s not good enough.

Arizona in 1995 enacted a statute known colloquially as the “stupid motorist law,” specifying that drivers needing to be rescued after ignoring signs warning them of a flooded area must pay for the rescue. (The law is enforced only spottily, however.)

That points to an obvious line of attack: through the court system. Unvaccinated people could be held civilly or even criminally liable if it can be shown that their behavior brought harm to others. That would require establishing a direct relation between an unvaccinated person and an infected victim, which can be difficult.

But patients infected in nursing homes where the staff isn’t 100% vaccinated, or housebound individuals infected after limited contacts with outsiders, might be able to connect the dots. “You have to have the right case, but I wouldn’t rule it out,” says Reiss.

As for billing unvaccinated patients for the cost of their medical care, the biggest obstacle might be the most important reform of the healthcare system in our lifetimes: the Affordable Care Act.

A key provision of the ACA bars insurance companies in the individual market from charging customers more based on their medical histories or denying them coverage altogether. It permits premiums in a given region to vary based only on smoking and, within limits, on the age of the customer.

That means that imposing a vaccination standard in the ACA market would probably require congressional approval. Whether that might happen probably depends in part on how rattled the lawmakers on Capitol Hill become from the spread of COVID, but politically, it’s unlikely.

It may not be necessary. Insured but unvaccinated people who end up in the hospital with COVID-19 already face high costs: They’re likely to breach their deductible and come up against their maximum out-of-pocket charges, which typically run to thousands of dollars.

Uninsured patients will leave the hospital, assuming they recover, with tens of thousands of dollars in bills.

“The community as a whole pays the price for people being unvaccinated,” says Peter Lee, executive director of Covered California, the state’s ACA marketplace. “But even more than that, those unvaccinated will pay the price — through illness, and through higher healthcare costs they’ll be paying out of pocket.”

That makes the discussion about imposing costs on the unvaccinated “a good thing,” Lee says.

Ivermectin, touted as a treatment of COVID by the anti-vaccine crowd, has “no effect,” according to a major study.

“It’s a reminder that we want to educate and encourage everyone to get vaccinated,” he says. “Paying a little bit more premium pales in comparison to the incentive of recognizing that if you end up in the ICU, you’re going to walk out with a $40,000 bill.” Insurance may pay part of it, “but is that really dice you want to roll?”

The fundamental rationale for the limitation on medical underwriting, or keying premiums to customers’ health profiles, was that insurance companies couldn’t be trusted to serve the public interest by making affordable coverage more widely available.

That hasn’t changed. Insurers are constantly looking for ways to shift costs to customers; witness their efforts to penalize patients for “unnecessary” emergency room visits — a policy that requires patients to exercise their own medical judgment and entails insurers defining “unnecessary” any way they wish. It’s conceivable that, granted the ability to distinguish between customers by vaccination status, insurers will try to claim that almost any condition that lands an unvaccinated patient in the hospital is connected to COVID and therefore not covered.

In any case, the ACA governs mainly private policies in the individual market, not those of big employers. Employer plans, which constitute a far larger market than individual plans, “could use financial carrots and sticks under wellness plans to encourage COVID vaccination,” Larry Levitt of the Kaiser Family Foundation has noted.

Wellness programs are supposedly designed to encourage healthful behaviors among workers, such as weight loss or smoking cessation (though the indications are that they don’t work). The danger is that they can become punitive if the penalties for disapproved behavior are excessive or the programs invade workers’ privacy.

Life, disability and even homeowners insurance carriers could rate customer policies by vaccination status. “There’s a big insurance world out there,” Caplan says, “and they should start taking vaccination status into account” when they set policy premiums.

That means that penalties for vaccine refusal should be carefully implemented so they don’t unduly burden communities of color or low-income populations that may have difficulty accessing healthcare even in normal circumstances.

On the other hand, Caplan argues, those who remain unvaccinated because they’re wary of side effects or can’t find the time or a place to get a shot may be easier to persuade to join the legion of the vaccinated. That leaves those who resist because of ideology or politics.

“I don’t think they’re either persuadable or incentivizable,” Caplan says. “We went through persuasion and carrots, so it’s time to think about what sticks will work.”

He’s right. Vaccination holdouts are turning into the greatest threat to public health during the COVID plague. When push comes to shove, people appear more likely to act to avoid financial or social threats to their lifestyle than the promise of a lottery win. That may be especially true if they don’t believe COVID is a genuine threat. It’s time, then, to stop pushing and start shoving.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.