Nissan Leaf: A revolutionary vehicle that drives like a car

No one loves lofty rhetoric and prosaic hyperbole more than car manufacturers. With a dollar for every time a mundane car was described as âexciting,â ârevolutionaryâ or ârace-inspired,â you could pull an Oprah and buy everyone on your block a Lamborghini.

But after a week of driving â and more importantly â living with a Leaf SL, itâs clear that this is what revolutionary looks like. Whether it is successful with consumers, however, remains to be seen.

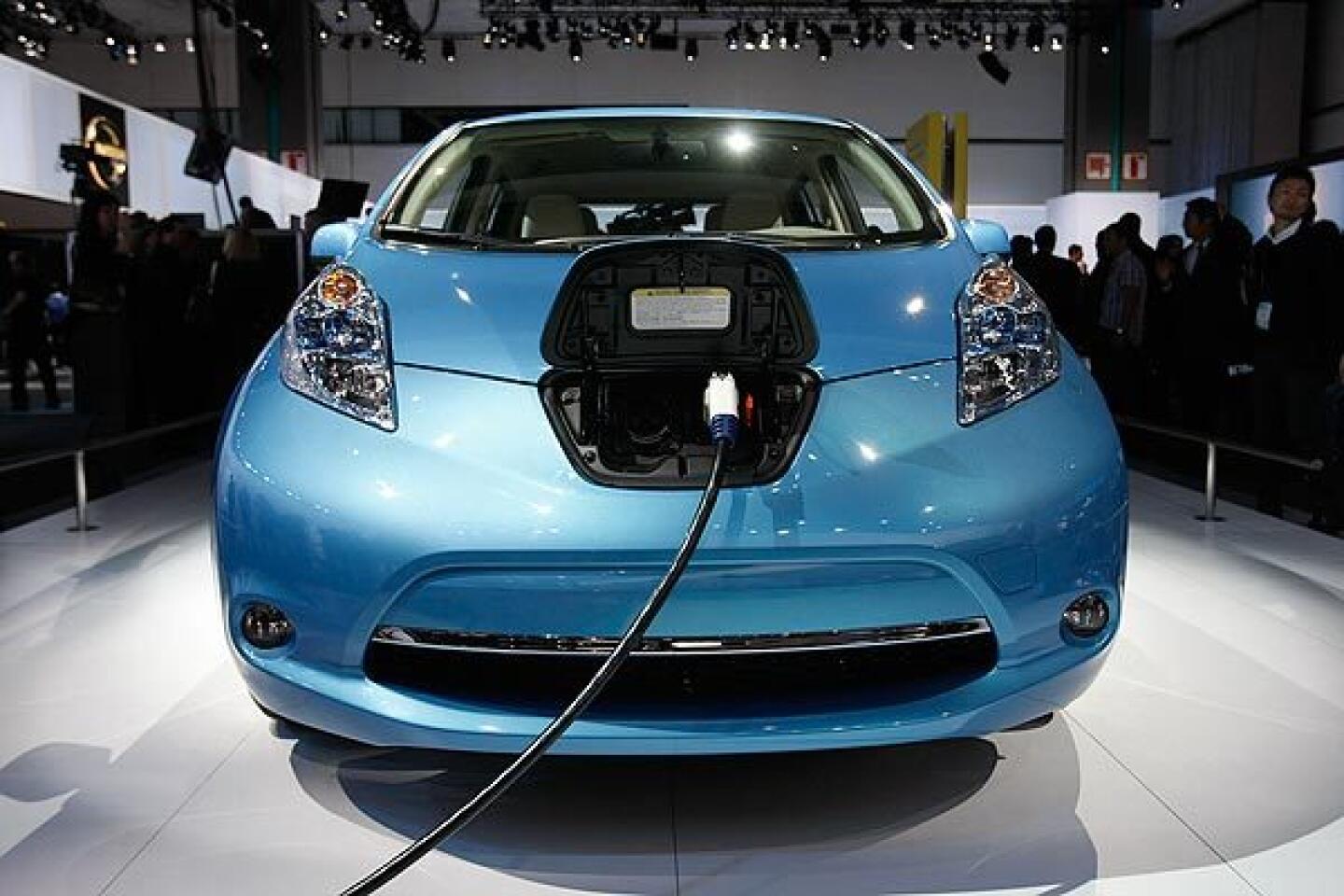

The Leaf is revolutionary because when it hits the road this winter, it will be the first mass-market all-electric car on the market and will start at $32,780 before tax credits. Kudos to Nissan Motor Co. for having the joules to devote the time (it started developing electric vehicles in 1992) and the expense (billions of dollars) necessary to bring the Leaf to production.

And in so doing, Nissan addressed the myriad shortcomings that electric cars traditionally have had in comparison with their internal-combustion brethren. Key among these are concerns about the carsâ practicality and cost and consumersâ range anxiety, a nascent term that describes the fear of running out of power before reaching the destination.

My time with the Leaf demonstrated that for all its innovation, itâs just a car. Itâs not a science experiment, or a spaceship or a pipe-dream prototype. Itâs a livable, enjoyable car that just happens to avoid using gasoline altogether because you plug it in at home to charge. A statewide network of charging stations is also in the works.

Except for the faint dentist-drill whine of the electric motor in place of an engineâs reverberations, thereâs really nothing very different about the Leaf once youâre on the road. The 80-kilowatt motor puts out 107 horsepower and a lively 207 pound-feet of torque, so acceleration is robust and smooth.

The motor is paired to a single-speed transmission. Drivers can switch the transmission from normal mode to eco-mode. This boosts the Leafâs range about 10% by increasing the regenerative braking and making it harder to accelerate with full power. Since there is so much torque available in normal mode, I was happy to leave the transmission in its eco setting and reap the increased mileage instead.

Nissan says the 24-kilowatt-hour, lithium-ion battery in the Leaf is good for about 100 miles on a single charge, while the Environmental Protection Agency says that number is actually 73 miles.

The Leaf charges from empty to full in about 18 hours using a standard 110-volt outlet as I did, or in eight hours using the 220-volt charger Leaf buyers can have installed in their home. This unit costs $2,200 and is eligible for a 50% federal tax credit.

Furthermore, through a grant from the Department of Energy, buyers of the Leaf and the Chevrolet Volt can get a home charger free of charge, with most or all of the installation covered as well.

Although 18 hours to fully charge your car may be a prohibitive burden to using an automobile, I found that at the end of each day, the Leafâs battery was rarely at or near zero charge. I learned to think of it as a cellphone; you bring it home at night with perhaps half the battery charge remaining, charge it overnight and use it in the morning.

Based on Southern California Edisonâs electricity rates, a full charge on the Leaf cost me a little more than $5.

I averaged about 85 miles on a single charge while driving it like a normal car. My commute is flat and includes 20 miles a day of freeway driving, which I did often at speeds of around 75 mph. I used the radio, the climate control when needed and kept the headlights on during the day.

Commuters in California should note that the Leaf will be eligible for the stateâs much-coveted HOV stickers providing carpool-lane access when the new batch is made available for 2012. (The Chevy Volt will not be eligible, Nissan is quick to point out.)

The Leafâs standard navigation system doubles as a dashboard-mounted Prozac for range anxiety. Easily accessible is real-time information on energy consumption, the effect of turning on or off the climate control, a map of how far you can drive in both normal and eco modes, and directions to the nearest charging stations.

Be warned, however, that most of the charging stations listed right now are useless because they have yet to be retrofitted for the Leaf and Volt.

Perhaps the biggest disappointment I had with the car was that using the climate control reduced the Leafâs range 15% to 20%.

Nissan tried to mitigate this effect by installing a timer on the Leaf that enables drivers to cool or warm the car while itâs still plugged in.

It handled like most other front-wheel-drive cars in its compact class, though the batteries bring the carâs weight to a portly 3,366 pounds. Nissan took this into account and mounted them beneath the rear seats to give the car a low center of gravity.

Space is great for full-size adults, and the rear seats fold down for extra cargo space.

The exterior styling is unique from any angle. This is a good thing at the back of the car, yet the bulging headlights in the front look as if the car is choking on its power cord. Overall, the styling is enough to denote the car as different, yet avoids throwing it in your face.

Thereâs more to the $32,780 base price than meets the eye. All Leafs are eligible for a $7,500 federal tax credit, bringing the price on the base SV to $25,280. California offers an additional $5,000 rebate.

So for about $20,000 excluding destination charge, Californians can get a compact, five-seat, four-door car that comes standard with such amenities as a navigation system, Bluetooth connectivity, LED lights, anti-lock brakes, traction control and alloy wheels.

My test car had the only option package offered for the Leaf, a $940 SL package that includes a backup camera, fog lights and a solar panel spoiler good for charging your cellphone.

Also included on all Leafs is an eight-year, 100,000-mile warranty on the battery and a five-year, 60,000-mile powertrain warranty.

My week in the Leaf required no cumbrous change in my driving habits or daily activities. Iâll be the first to admit the Leaf is not for everyone, namely single-car households or people who drive more than 100 miles a day.

But with most Americans driving 40 miles or fewer a day, the Leaf makes a strong case to forgo internal combustion and step into a revolution.