Grounded, in a good way

There are few words that strike more fear into the hearts of studio executives than “stage mother.” Hollywood lore is filled with parents who have sent their children to work, with successful if heartbreaking results for everyone from Buster Keaton, to Judy Garland, to Macaulay Culkin, down to out-of-control starlet Lindsay Lohan.

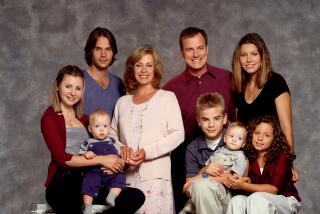

Debbie Boyd, mother of child actors Jenna, 12, (“The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants”) and Cayden, 11, (“The Adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D”), wants it to be known that she’s not one of those mothers. It’s a Wednesday afternoon not long before the premiere of her children’s films, and the Texas-bred Boyd along with Texas-bred husband Michael and their mini-Jack Russell, Tippie, are hurtling along in an SUV on the way to pick up their children at their parochial school deep in the San Fernando Valley.

Debbie Boyd has the buoyant, friendly demeanor of a former flight attendant (which she was) and the determination of, well, a stage mom. The kids’ acting careers are her gig -- and Michael, a former Navy “Top Gun” aviator turned Delta pilot, indulges her, a little like how Ricky used to indulge Lucy on “I Love Lucy.”

“He steers clear of this whole Hollywood thing. It drives him completely crazy, so he pretty much lets me handle it,” says Debbie. Except for the occasion when Dad has to play ringer for meetings. “I say, ‘Just take Cayden here, stand here, be nice, don’t say anything. Sign him in, and wait until they call his name.’ ”

The Boyds pointedly don’t manage their children’s careers, and don’t live off their earnings -- two cardinal rules that, when broken, can wreak havoc on family dynamics. As Debbie says succinctly to anyone who ever asks, “You can’t parent if you are financially reliant on anything they do at a given time.” As the Boyds wait on the lawn of their children’s school for the bell to ring, Debbie confesses that she’s trying to keep it all normal, telling Jenna for instance, never to play the starlet at school, to be gracious but not to sign autographs, and “if anybody asks you a question about yourself, ask two about the other person.”

When Jenna finally appears, she does seem like a regular 12-year-old, dressed albeit neatly in a striped top and knee-length white skirt. She’s giggling with her friends, who giggle even more when they realize a photographer is there to take her picture. “Hey, Jenna, do you have your own photographer?” one asks. All the girls, save Jenna, get excited and vamp when they realize he might actually take their pictures too. They play patty-cake and clump together in a huddle to chat, until Cayden finally arrives.

If Jenna is spunky (but not in the annoying Disney Channel “s-p-u-n-k-y” way), Cayden appears vulnerable and dreamy, but not so much so you can’t imagine him playing T-ball. (He plans on football for next year.) He played Tim Robbins’ son in “Mystic River,” though his parents pointedly never showed him the whole movie. Today, he excitedly shows his dad a friend’s photograph of the Kitty Hawk aircraft carrier.

“He’s very naturalistic, a kind of quiet little boy in person,” says Robert Rodriguez, who cast Cayden as the lead in “Sharkboy and Lavagirl.” “It’s very much like the character. It’s like how I like to cast, not the kind of kid who comes in and takes over the room with his boisterous personality. That’s not how a real kid is. He seems well-trained too. He knew enough about acting to not act. It felt fresh each time.”

Mom knows best

Even though she has no professional acting experience, Debbie in fact does coach her kids in part so directors won’t get the same factory-induced reactions that happen when a drama coach has coached 20 children for the same part. Also, she thinks, who else understands her children’s emotional psyche as well as she does?

For instance, when Jenna auditioned to play the youngest daughter in the family for the tough Ron Howard western “The Missing,” “I knew that no one could tap into [her emotions]. Nobody would spend the time. We went through this script talking about how this character must feel. This was something she’s totally not able to relate to. Please. The worst day in this child’s life was the day she found out there wasn’t any Santa Claus, and I’m trying to explain to her ‘Now, your [character’s] sister has been kidnapped, your family’s been slaughtered.’ There was probably 20 hours of talking before you even got to a line.”

“She’s really, really good. She understood and emotionally connected with that character in a really honest way. Talk about a family and a kid who’s got her head screwed on straight,” says Howard, himself a famous former child actor, who appears to have emerged unscathed. “She is very much a result of their influence.”

On the way home, Debbie goes over what they have to do for homework (Bible and spelling). Jenna’s been up since 5, to practice figure skating before school. This afternoon, she will have a fitting for her dress (suitably appropriate for her age) for the premiere of her film, while Cayden will practice baseball with the director of his new film, “A West Texas Children’s Story.” There’ll be a few phone interviews and then bed, by 8.

Back in their condo, the family’s rooms seem barely decorated, although each child has a comfy, immaculately neat lair with scant movie memorabilia. Jenna’s has miniature American Girl setups but keeps her American Girl dolls in drawers. Although she tried out for the American Girl movie, in real life she has essentially moved on. In her off time, she likes instant messaging her pals on her pink instant-message gadget. (Her mom won’t let her have a cellphone.) She has no memories of life before acting. “I have been acting since I was so little, and I can’t remember before I was 2,” she says.

In Cayden’s room are mini-football pennants and a collection of jackknives, including one with the likeness of President Bush and another of NASCAR legend Dale Earnhardt, as well as new, cool tie-in material from “Sharkboy and Lavagirl” that Cayden’s flipping through for the first time. There’s also a drawing from an upcoming TV series, in which he plays a kid who has to testify against his father, who locked him inside the house for two years. Asked if it’s hard to do a scene like that, Cayden just shrugs. “Everyone can teach themselves to cry ... but sometimes you have just got to see that mental movie going on. You’ve got to be feeling it.”

Cross-country road to stardom

While the Boyds work hard at keeping an air of normalcy, working your way up the Hollywood food chain doesn’t just happen. Debbie entered Jenna in a modeling competition in Fort Worth when she was 2. They did print ads and commercials, eventually leaving Texas for Atlanta for Michael Boyd’s job. Only 14 months younger than his sister, Cayden just came along for all the auditions and eventually got cast too. In 2000, their Atlanta agent suggested they try their hand in the big leagues.

Debbie wound up living in the temporary Oakwood apartments for a year with the two kids in a one-bedroom apartment. Things were so up in the air, she home-schooled them, which, she admits, was tough on her sanity. Every TV pilot season, the Oakwood apartments are crammed to the gills with stage parents and their progeny trying to make it.

“It’s fun for the kids. I think it’s not fun for a parent,” says Debbie. “It’s just in a bubble. You can’t go to the laundromat without overhearing mothers talking about what auditions their children went on. I don’t think it’s a mentally healthy place.” Fortunately, that era is long past. The kids are on their way, so much so that they turn down parts, opting to work primarily in movies. Now Debbie just has to worry about making their two schedules mesh, so she can always be on-set.

If Jenna and Cayden seem relaxed about the movie business, that’s because the Boyds try to shelter them, never talking about grosses or box office.

As the day draws to a close, Debbie finally admits it’s herself that she has to constantly monitor. She’s the one who can get “sucked in” by the Hollywood vortex, and she never wants to lose sight that her first role in life is as their mother.

“You can find a lot of good managers in this town and you can find a lot of good agents, but you can’t find but one mommy and daddy who [are] going to care for them like we are,” she says. “So I can’t lose myself and I will, you know. It is not that I’m not beyond it. I have better perspective on it some days than others, but I have to fight for it every single day.”

She always reminds herself that if Jenna and Cayden never made another movie, “it’s been lovely. [We’ll] go back to Texas, and we’re going to be proud of what we’ve done and we’ll move on. They will still be happy, healthy kids.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.