The devil made them draw it

Scholars of popular culture have long analyzed the dichotomy of good and evil in comic books. Readers have embraced the tension between good and evil so much that superhero comics have been called the new mythology for the 21st century. Making sense of the villainous has been a frequent topic of discussion since the “grittification” of the hero and the rise of the anti-hero, trends that began in the mid-1980s when artist Frank Miller and writer Alan Moore re-imagined characters for their “Batman: The Dark Knight Returns” and “Watchmen” series, respectively.

In “The Comics Go to Hell,” Scandinavian scholar Fredrik Stromberg pays tribute to these themes while exploring the subject of the devil as he appears in comics the world over. Although the book does not focus exclusively on super-villainous archetypes -- which he dubs “superdevils” -- the author serves up sufficient commentary and visuals on the underworld’s evil menaces and minions to intrigue readers.

“As long as there are comics with superheroes, the Devil will always have his place in the comics medium,” he writes. “He is the ultimate standard against which the heroes are measured.” His book suggests how well-suited the devil is for the superhero world because Christian themes and motifs often form the basis of storytelling. Both heroes and villains have sold their souls; the prideful super-villainous have sought world domination; salvation and redemption are commonplace; and battles between the forces of heaven and hell abound.

A sampling of underworld villains in this book includes Marvel’s super-demon Mephisto, whose arch-nemesis is the Silver Surfer, and the no less intimidating demon Satannish, who went head to head with Dr. Strange and unleashed his Sons of Satannish against him. The reader also finds, from DC Comics, the figure known as First of the Fallen, a runner-up to Lucifer and eternal tormentor of vigilante John Constantine; Beelzebub, who for a time ruled Hell with Azazel and Lucifer and, in human form, combated the heroes Kid Eternity and Supergirl; and Lucifer, who, after resigning from the throne of Hell, lives in Los Angeles as a sort of supernatural anti-hero.

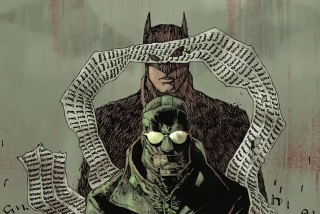

Todd McFarlane’s phenomenally successful superhero Spawn reminds one of previous heroes such as the Golden Age Spectre and Deadman, whose stories explored the consequences of striking bargains with the forces of darkness. In the Spawn comics, we meet dead Marine Corps soldier Al Simmons, doomed to a life in hell, who makes a deal with Malebolgia, the demonic overlord of a Dantean “eighth sphere of hell.” Simmons returns to the world of the living as the hell-born superhero, bent on waging a one-man war against all things evil.

Unlike Spawn, Mike Mignola’s half-man/half-demon Hellboy is a hero archetype whose comic book liberally mixes dark humor with pulp references and paranormal themes. Described by Mignola as “the world’s greatest occult detective,” the red-skinned behemoth is a force for good as a member of the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense. Despite this, he constantly struggles with his demonic heritage and may actually be the Beast of the Apocalypse. Given his genetics, Stromberg projects, “it is likely that sometime the protagonist will go to Hell for a confrontation with the Devil.”

“The Comics Go to Hell” also includes European comics and graphic novels, including Danish cartoonist Peter Madsen’s “Menneskesonnen” (The Son of Man), existentialist Italian-born artist Hugo Pratt’s “Les Helvetiques” and Jonas Andersson et al.’s Swedish alternative superhero comic “Korsmannen” (Cross-Man) -- all interesting in their own right however foreign to a general American public.

Because, as Stromberg points out, the devil is “the most potent symbol of pure evil that exists in the Western world,” comic books and strips have made frequent use of the image. Dig deep enough and you’ll find him where you least expect (even, as Stromberg shows, in the 1940s syndicated “Mickey Mouse” daily strip).

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.