Saddam’s chief apologist

- Share via

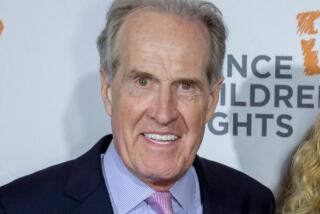

NOT MANY MONTHS ago, on this very page, a former attorney general of the United States defended his own decision to appear as an attorney for Saddam Hussein. In his article, Mr. Ramsey Clark made the perfectly obvious and indeed irrefutable point that his infamous client -- his “demonized” client, as he phrased it -- was as much entitled to a defense counsel as the next man.

Nobody disputes this proposition, least of all the Iraqi court that Clark described as illegitimate before it had even opened proceedings. So now, Clark -- one of the chief spokesmen of the American antiwar movement, leader of the ANSWER coalition that filled the streets with protesters and compared President Bush to Adolf Hitler -- is indeed in Baghdad, seated at the defense table for a client who on Monday terminated the proceedings by loudly comparing his own stand in the dock to the heroic struggle of Mussolini.

Any reporter with the smallest talent could make good copy out of this zoo-like scene. But a core of principle is involved here, and it ought not to be overlooked. Hussein stands accused of some of the most revolting crimes ever perpetrated by any despot. A defense lawyer is (presumably) engaged to acquit him of such charges. Yet before he had even had his credentials accepted by the court, Clark announced that his client was a) guilty of disgusting atrocities and b) justified in having committed them.

To be exact, in an interview with the BBC last week and another in the New York Times on Tuesday, Mr. Clark addressed the charge that in 1982, after an apparent attempt on his life in the Iraqi town of Dujail, Hussein had ordered the torture and murder of about 150 men and boys from the area.

Far from denying that any such horror had occurred -- and it is one of the smaller elements in the bill of indictment -- Clark asserted that it was justifiable. He has now twice said in public that, given the war with the Shiite republic of Iran, Hussein was entitled to take stern measures. “He had this huge war going on, and you have to act firmly when you have an assassination attempt,” he told the BBC.

To this he calmly added that he himself had more than once been shoved aside by Secret Service agents eager to defend the president of the United States (and of course one remembers the mass arrests, beatings and executions that followed the assassination attempts on presidents Ford and Reagan). It is as if Hussein had not started, by his illegal, blood-soaked invasion of Iran, the “huge war” that Clark cites as the excuse for Hussein then turning his guns on Iraqis.

I wonder, does the former absolute owner of Iraq quite realize that one on his team of attorneys is proudly trumpeting his guilt?

Never mind for now whether the despot has engaged a bad counsel: This raises another subject that ought to concern all serious Americans. In the run-up to the war, almost whichever way the debate was going, one could count on the president’s opponents to stipulate that, yes, Hussein was certainly a dreadful and criminal figure. This position was hardly optional, given the Alps of evidence assembled over the years, much of it later excavated in mass graves and torture centers and in the ruin of two neighboring states.

Yet now, one of the best-known spokesmen for the antiwar cause appears across the world’s TV screens, openly saying that the Hussein system was justified all along in its aggression abroad and its fascism at home.

I was, and still am, one of those who advocated publicly for the overthrow of Hussein. In debates, I proposed that most participants could at least agree on something. Whatever one’s view of the propriety and competence of the intervention, it could surely be accepted that human rights groups in Iraq could use some help digging up the mass graves and identifying the missing; that women’s organizations needed allies against the fundamentalists on both sides of the argument; that the Kurdish people -- the largest stateless minority in the region -- were in need of solidarity; and that the “marsh” Arabs, victims of one of the worst ecocides ever inflicted, were calling for help.

For the most part, the antiwar faction has subordinated everything to its hatred of Bush, folded its hands and watched coldly as Iraqi democrats struggle in a sea of chaos and violence. That sham neutrality is bad enough. But now, the anti-warriors do have a permanent representative in Baghdad, in the form of an apologist for the past crimes and aggressions of a man who makes his hero, Mussolini, seem like an amateur.

I wonder: What will Cindy and the other humanitarians say this time? Or are they not “antiwar” at all, but simply pro-war and on the other side?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.