U.S.-Philippine Mission Hits Snag

MANILA — The Bush administration is all set to bring its “war on terrorism” to the Philippines. Hundreds of Green Berets, Navy SEALs and Marines are preparing to land on Jolo island and hunt down the Abu Sayyaf, a ruthless gang of kidnappers who style themselves Islamic militants.

There’s just one snag. The Philippine government, after apparently agreeing to let U.S. troops engage in combat, is balking now that the deal has become public.

On Sunday, Philippine Defense Secretary Angelo Reyes flew to the United States, where he is to meet this week in Washington with Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld and other officials. Philippine officials said Reyes would negotiate the terms of U.S. involvement -- terms that the Pentagon, when it announced the involvement last week, seemed to think had been worked out.

Ignacio Bunye, spokesman for Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, said Sunday that no final agreement had been reached with Washington and insisted that U.S. troops would not be allowed to fight in the Philippines, despite what the Pentagon has said.

“They will not be on combat missions,” Bunye said flatly in a radio interview.

If the Bush administration is compelled to modify its plans for the Philippines, it would be a setback to its effort to use military force to eradicate perceived threats to U.S. interests around the globe.

Even as the U.S. focuses on Iraq, it is eager to show it can fight suspected terrorists elsewhere. A refusal by the Philippines could embarrass the U.S. and highlight the reluctance of even close U.S. allies to grant permission for military intervention.

The Pentagon announced last week that the U.S. was sending 3,000 troops to help hunt down members of Abu Sayyaf. But the Philippine Constitution prohibits foreign troops from fighting on Philippine soil, and there is strong opposition to changing or circumventing the law.

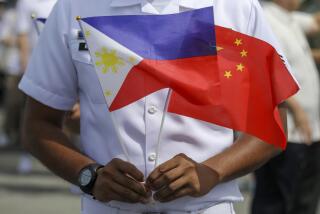

The Philippines, a U.S. colony until 1946, is one of America’s strongest allies in Asia. Many Filipinos feel a kinship with the United States, American products are sought after, and English is widely spoken.

At the same time, Filipinos believe strongly in their independence. In 1991, the government refused to allow the United States to continue stationing troops at two major military bases, Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Station.

Arroyo, who took office the same day as President Bush, was quick to join in U.S. anti-terrorism efforts after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the Pentagon and New York City.

Last year, the U.S. sent troops to the southern Philippines to train Philippine soldiers in methods of combating the Abu Sayyaf, whose leaders had links in the mid-1990s to Osama bin Laden, although it’s not clear whether any connection still exists.

U.S. trainers accompanied Philippine soldiers on patrols but were authorized to fire their weapons only in self-defense. The U.S. also provided equipment and intelligence assistance to the poorly funded Philippine army.

With the U.S. help, Philippine soldiers pushed the Abu Sayyaf off Basilan island, where they were hiding in the dense jungle with two American hostages, missionaries Gracia and Martin Burnham. U.S.-trained Philippine soldiers subsequently rescued Gracia Burnham, but her husband was killed in the raid that freed her.

U.S. troops stayed on Basilan to build roads and provide other social services, creating goodwill there. Today, the training mission is widely considered a success.

However, dozens of Abu Sayyaf members from Basilan fled to Jolo island, the group’s stronghold. About 200 fighters are engaged in frequent battles with the Philippine military.

Both governments sought to expand on the Basilan success by enlarging the role of U.S. troops in combating Abu Sayyaf. Negotiations between Washington and Manila have been going on for months over the next phase of the joint operation.

Before departing for the U.S., Reyes reiterated to reporters at the airport that U.S. troops would not take part in any fighting on Jolo.

“The guidance of the president is very, very clear,” he said. “There will be no violation of the constitution or any of its laws.”

Arroyo’s critics believe her government negotiated a secret agreement with the Pentagon to allow U.S. troops in combat but disavowed the deal once it became public.

Among the critics is Sen. Aquilino Pimentel, who said he was shocked by the Pentagon’s announcement, and went so far as to accuse Reyes of treason.

“My take is that Secretary Reyes is trying to cover up for what was actually a done deal between the department of national defense and the Pentagon,” he said. “Somebody is lying, and it’s our own people.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.