Strawberry Faces Pitcher on Different Field

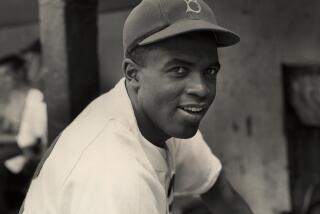

TAMPA, Fla. — Long ago as young men, Darryl Strawberry and Robin Fuson faced each other on the field, one a tall, skinny batter destined for stardom, the other a strong but wild pitcher who would never make the big leagues.

They stood now a few feet apart in a wood-paneled courtroom, Strawberry receiving a light sentence from a judge and a death sentence from his doctors if he keeps up his ways, Fuson guiding the prosecution as chief of narcotics in Florida’s state attorney’s office.

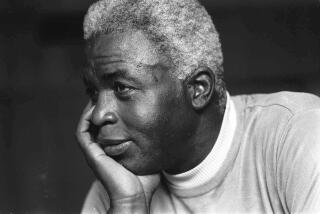

Strawberry, head shaved, eyes downcast, wearing the county jail inmate’s orange jumpsuit, blue jacket, white socks, sandals, and heavy shackles on his wrists and ankles. Fuson, thick-maned and alert, in a three-piece suit and a diamond-studded 1989 World Series ring from his stint as a pitching coach for the Oakland Athletics.

They didn’t speak to each other and Fuson let an assistant handle the questioning. Afterward, Fuson doubted that Strawberry even remembered their first meeting in instructional league in 1981.

“I pitched against him four times--struck him out three times, hit him in the head once,” said Fuson, who was in his third year of the Cleveland Indians’ organization. “Funny thing was, the ball bounced off his helmet and I fielded it and threw to first. The ump called him out because he thought it was off his bat.”

Strawberry was the No. 1 pick in the baseball draft for the New York Mets out of high school that year. Scouts called him a “black Ted Williams” because of his lanky build and graceful swing, and he signed for big money. A few years later he would be the NL Rookie of the Year.

While Fuson struggled through the minors and eventually left the game for law school after a 10-year career and a credible 120-70 record, Strawberry’s story took one tragic turn after another even as he kept slugging homers.

He abused alcohol, women and drugs. He developed colon cancer, had surgery and chemotherapy. He came back to help the New York Yankees win the World Series last year, then had his left kidney removed in August when a new tumor was found.

“I’m not going to say, ‘Oh, what a waste of a career.’ Because careers are wasted before they ever start for 1,000 reasons,” Fuson said. “He could have had it all. He could have kept it all. But he chose not to. And it’s just as tragic that Darryl Strawberry threw it all away as it is for every one of the 17-year-old kids that I see come through here every day.”

It is a realization that is just hitting Strawberry as he spends his days in jail among addicts, thieves and thugs. For years, he slipped past his problems with a sweet smile and a winning personality, conning his friends, his fans and himself into thinking everything would be all right. Now he knows it won’t.

“My career is over. Done,” the 38-year-old Strawberry said in an interview from jail that will air on “Dateline NBC” Sunday night. “I’m physically not able to go anymore, and I just don’t have the desire to go anymore.”

In truth, there was no question of him playing again after his latest illness and recent relapse into smoking crack cocaine while violating probation a third time.

Though he still looks strong and athletic, he knew he’d never play again even as his friends on the Yankees and Mets met in the World Series this year. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the cocaine relapse occurred during the Series.

Strawberry said last week that on the night he sneaked away from a rehab house to smoke crack with a female friend, he had given up and wanted to die. Now, he says he wants to live, but he might no longer have a choice. For the first time, when his doctor testified in court Thursday, Strawberry seemed to realize that his life, not just his career, is in grave peril.

“He has a very aggressive cancer,” Dr. Jonathan LaPook of New York Presbyterian Hospital testified by telephone. He said the cancer is “very likely” to recur, and strong, immediate chemotherapy is needed, possibly with experimental drugs that, because Strawberry has just one kidney, should be given only at certain qualified university medical centers.

“The window of opportunity for treating him,” LaPook said, “is sort of closing. ... We are in an emergency situation right now, and we have to act like that.”

Dr. Robert Fine, head of experimental oncology at the same hospital who is working with LaPook, emphasized the dire outlook in a letter read in court.

“The chance of relapse is close to 90 percent,” Fine wrote. “If he does not get this chemotherapy, the tumor will most likely relapse and that will mean certain death to Mr. Strawberry.”

Yet Strawberry has stopped taking the chemotherapy in jail, and he will stay in jail at least another week. He will then go back to HealthCare Connection, a clinic in a small, shoddy building with no security gates in an area just north of Tampa where drugs of all kinds are easily bought.

Although he will be required to wear an electronic monitor on his ankle and will not be permitted to leave the center or drive, there will be nothing to stop Strawberry from doing either one--except the fear of going to prison if he does.

“There’s an incredible amount of dope being sold in that area,” said Fuson, who went to high school near the center. “I think he’s going to fail. I know that sounds cynical. But it’s based on his addiction. I would say within five months.”

Strawberry insisted in court that he will make an effort to stay clean.

“I’m willing to commit to rehabilitation,” he said. “I’m not going to allow anybody to run me out of town.”

Judge Florence Foster turned down the prosecutor’s request that Strawberry be sent to prison--he could have received a maximum 5-year term--and instead went along with a probation officer’s recommendation to give him 30 days in jail, less about 20 days for time served.

“If you can’t make it on the outside, I’ll find a place where they’ll give you treatment on the inside,” Foster told Strawberry. “I think you’ve had an eye-opener today. You have an understanding. If you don’t get your chemotherapy you will die. I don’t think your doctor has spoken to you this directly before ... that it’s an emergency.

“You’ve got to get that therapy or you’re history.”

Strawberry wore a somber expression, as did his friend and former teammate Dwight Gooden, who sat at the back of the courtroom.

LaPook stressed that Strawberry has no chance of recovery from the cancer if he does not beat his addiction to cocaine.

“In this case,” LaPook said, “we don’t have room for error.”

Strawberry will receive the chemotherapy at the rehab center, not in the kind of controlled setting described as necessary by Fine and LaPook. They would prefer that he go to a “world class” hospital, like the Mayo Clinic or Hazelden Foundation in Minnesota, for dual treatment of his addiction and cancer.

Strawberry and his attorney were happy that he won’t have to go to state prison. But from what his doctors said, and the way Fuson dimly assessed the chances of success in overcoming cocaine, Strawberry’s future looks terribly bleak.

Fuson sympathized with Strawberry’s struggle but was convinced that he had gotten his chances and blown them, that baseball had treated him too leniently, that he was a danger to the public if he drove again while drunk or on drugs, and that he deserved punishment as much as treatment.

“I don’t see him any different than I see anybody else that’s jammed up,” Fuson said. “I’m not star-struck. I believe that the doctors involved in this case were star-struck. Darryl Strawberry is a convicted felon. He’s a criminal. Darryl Strawberry is not a baseball player. He used to be. I used to be a baseball player. He is in the system now and he’s going to be treated the same by the state as anybody else in that situation.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.