Global Economy: Is Popular Trend a Giant Step Backward for Humankind?

Inevitability, it seems, does not invite deliberation. And these days, the pell-mell rush toward a global economy is evermore accepted as unstoppable. The questions yes-or-no, good-or-bad fade as politicians and executives wrestle to gain advantage in the vast “playing field” of planetary economics.

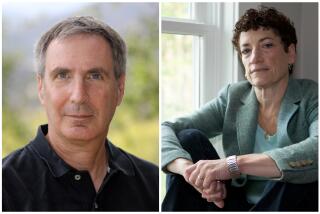

Jerry Mander is worked up wondering why.

“People describe this idea of the global economy as if it were a force of nature. But it is, actually, a thought-up system,” says Mander, who is co-editor of an exhaustive and provocative new book called “The Case Against the Global Economy.”

“It is only inevitable,” he adds, “if we say it is.”

As Mander sees things, if he and the 40-plus international authors in this collection are only the tiniest bit right, then those invested in globalization are surely wrong: The impending one-world economy can be checked, undone or resisted. The book, now in its second printing after only six weeks, further argues that it is in humankind’s selfish interests to do so.

A longtime environmentalist and senior fellow at the nonprofit, conservationist Public Media Center in San Francisco, Mander says there are too many emerging signs of discontent from different places in the world and from varying ideologies to continue to marginalize those who question the wisdom of an unfettered global corporatism.

“If you speak out, you are trivialized as protectionist and isolationist, which turns out to be a good way of dismissing us. But the global economy is a disaster for the environment, a disaster socially, a disaster for small farmers, it drives wages down and is a giveaway of sovereign power to corporate bureaucracies,” Mander says.

In the recent presidential election, Patrick J. Buchanan, Ross Perot and Ralph Nader all voiced such warnings without avail. America’s two marquee trade treaties--GATT and NAFTA--remain subjects of dispute, but opponents are finding it harder to hold an attentive audience.

The trend, however, does not prove a truth, Mander argues.

“I believe that even the giant corporations who champion this know it’s not sustainable. But they don’t know what to do about it. . . . This globalization has not made people more secure. Their security is greatly threatened. Their jobs are threatened. Their environment is threatened. It is not satisfying human needs.”

Fact is, at least right now, trade is not as huge a part of the U.S. economy as the headlines may suggest. A study by Douglas Irwin in the American Economic Review found that merchandise exports as a percentage of the gross national product are only slightly higher now than a century ago.

But it is the theory and policies of so-called 21st century free trade that disturb Mander, in particular the growing power of nations to challenge each other’s laws and traditions on behalf of their commercial exporters. The U.S. protection of dolphins, for instance, has been challenged as a trade barrier by tuna fishermen in other countries. The Clean Air Act and other long-standing American policies also are under fire. Surely more will follow.

“People are not going to be very happy,” he says.

He acknowledges that one of the founding premises of unregulated trade is that it will reduce the temptation of participating nation-states to engage in armed conflict. Better to fight over the dollar, yen and mark in the Atomic Age. But Mander believes that mass discontent will arise--is arising--with a system that results in colossal disparities of wealth between corporate tycoons and corporate employees.

“This doesn’t lift all boats, it’s lifting yachts. Eventually, the only way order can be maintained is through oppressive means,” he says.

But if not a global economy, then what?

That, Mander argues, should be the next great debate in America.

“If your car is headed for a cliff, the first thing you do is stop it and say: ‘We’ve been given a faulty road map.’ From there, deciding the right direction is always a bit complicated,” he says.

He would argue for a simple concept of business: “Site here to sell here.” After all, America originally chartered corporations in the name of public good, not for the gain of investors.

John Maynard Keynes, whose economic theorem has been a factor in Western policy for 60 years, is best known as an advocate for government intervention to maintain employment.

Sometimes overlooked is what he said about global trade: “I sympathize . . . with those who would maximize economic entanglement between nations. Ideas, knowledge, art, hospitality, travel--these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible; and, above all, let finance be primarily national.”

Or as former World Bank senior economist Herman E. Daly writes in this new book, free trade ceases to be free when “nations are no longer free not to trade.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.