Science / Medicine : The Lies That Bind: Nearly All Species Deceive : Life: Deception is not only useful, experts say, it is often a necessity that allows organisms to survive.

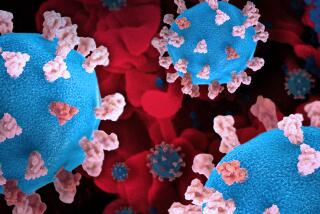

The herpes virus is a crafty sort, cloaking itself in the familiar wrapper of a human protein like a wolf in sheep’s clothing and persuading body cells to welcome it inside, where it can subvert the cells’ machinery for its own purposes.

An African beetle, equally deceptive, attaches the carcasses of dead ants to its body so that it can enter an ant colony undetected and gorge itself.

Greek warriors hid inside a massive wooden horse to gain entry to Troy, sneaking out in the night to slaughter their foes.

From the smallest living organism to humans, virtually all species practice deception, scientists are coming to realize. And contrary to the moralistic attitudes that suffuse our society, experts say, deception is not only useful, it is often a necessity that allows the organisms to survive.

Viruses con cells to aid their propagation. Insects simulate the protective coloration of leaves or foul-tasting brethren to increase the odds of their survival. Chimps misdirect their pack mates to get a little extra food. Humans lie--to themselves and others--to maintain their personal esteem and the cohesion of their societies.

“Nature offers niches for deceivers at every level in the organization of life, from one-celled organisms to complex confidence scams,” said Loyal D. Rue, professor of religion and philosophy at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. “There is now sufficient evidence to warrant the conclusion that deception is often adaptive. . . . The ‘lies’ we see in nature and culture are life-support systems. We can’t survive without them.”

But humans distinguish themselves by taking the process one step further, according to anthropologist Robert W. Sussman of Washington University in St. Louis. “All animals are able to think, and many can use tools,” he told a recent meeting of the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science in Washington. “What sets human beings apart is our ability to deceive ourselves.”

That capacity began more than 100,000 years ago, he said. “In the fossil record, the tools of Homo erectus show very little variability. Then all of a sudden you get variations on tools, burials, effigies, art--things with no practical use. It’s the first time you can say humans are symbolizing. I say that at this point you get self-deception--they are creating worlds that don’t exist.”

Burials indicated a belief in an afterlife for which the body needed to be preserved, he noted, while effigies were usually of gods and goddesses.

Furthermore, Rue argued, “humans are unable to achieve the only two things that really matter--personal well-being and social order--without self-deception. Cultures achieve these two goals by making large, comprehensive cultural myths. Without them, we don’t have the resources for survival.” Among those myths are humanity’s stories, legends, folklore and ideologies ranging from communism and socialism to religions.

Unfortunately, he added, over the last 200 years, humans have used science to expose the extent of self-deception in society. Studies of the stars, for example, have revealed the deception of astrology, while the efforts of paleontologists have overthrown the myths of creationism. As a consequence, value systems such as communism, socialism and even the Judeo-Christian ethic have become less convincing, and humanity has “developed an immunity to mythological thinking.”

Humans, he argued, are losing the myths that bind them together and create social cohesiveness, replacing them with individual world views that are far more self-centered and detached from society as a whole. Altruism has become less common, egotism more frequent.

Volunteer agencies go begging for assistance while their former helpers work out in the gym to bolster their own self-image. Membership in churches declines while membership in gangs leaps upward.

What society needs now, he argued, is a new “noble lie,” a mythos “that deceives us, tricks us, compels us beyond self-interest, beyond ego, beyond family, nation, race, even beyond the self-evident truth that human beings are the crown of creation.” The noble lie will deceive us into placing other people, or the Earth as a whole, above self. The concept of Gaea, the Earth as living organism, is “a hell of a kernel” of one possible myth, he noted.

While humans deceive themselves, most species deceive only others.

“Deception between species probably has been around since the first predator-prey relationships were established,” and it is particularly apparent in the world of microorganisms, said biologist Ursula Goodenough of Washington University. “Numerous pathogens operate by deception. . . . We must understand their deceptive ways and figure out how to outsmart them.”

Some microorganisms, like the herpes virus, cloak themselves in foreign proteins to gain entrance to cells. Others, like the viruses that cause influenza, can change identifying proteins on their surface so they will not be recognized by the human immune system.

Some pathogens have the capacity to produce vast repertoires of such identifying markers. The trypanosome protozoan that causes African sleeping sickness, she noted, can produce more than 1,000, enabling the microorganism to persist in the body.

Examples of deception among animals are much better known to most people. The viceroy butterfly, for example, is a delicacy for birds, but evolution has colored its wings to mimic the markings of the foul-tasting monarch butterfly, forcing the birds to think twice before attacking it.

Certain male bluegill fish mimic both the appearance and courting behavior of females to enter the territories of dominant males and fertilize the eggs of females. Some male scorpion flies also mimic the posture and behavior of females to steal the nuptial offerings--dead insects--of other males. They then present the insects to females themselves to mate.

Some male fireflies emit the distinctive flashes of willing females to lure other males, which they then eat.

Cuckoos trick other birds into raising their young by laying their eggs in the other birds’ nests. Male pied flycatchers deceive females--who will not mate with an attached male--by establishing a second territory far from their first. In this manner they have twice the reproductive success.

A cat, backed into a corner, makes its hair stand on end so that it appears much larger than it actually is.

None of this behavior, of course, is voluntary. It is just as embedded in the organisms’ genes as are size, color, biochemistry and other characteristics. But the slight survival edge produced by such tendencies has been reinforced over countless eons, until the traits have become integral parts of the organisms’ characters.

The more intelligent the animal, the more likely it is to practice voluntary deception, especially toward members of its own species, Sussman said. Voluntary deception is common in primates, he noted.

In another well-known study, researchers permitted a young chimp to watch while they hid bananas in a field. They then released it along with other chimps. The first couple of times, the youngster went directly to the food, but it was taken away by the other animals. After this had happened a few times, however, it learned to head off in another direction to throw the dominant chimps off the track, returning to retrieve the bananas only when the coast was clear.

“These kinds of studies show that the chimps can think about the self and others,” Sussman said. “But I think there is another thing that you have to postulate: These animals obviously have a complex way of imagining outcomes of interactions. In their head, they have a whole scenario of what might happen. . . . This is a sign of imagination.”

Imagination, he added, is a necessary component of self-deception. But he believes only humans are capable of that.

Even self-deception can have evolutionary advantages, according to biologist Robert L. Trivers of UC Santa Cruz. Studies have shown, for example, that people with positive self-images--even when based in part on self-deception--are usually happier and healthier than those with low self-esteem. Self-deception also “allows an individual to be more convincing” to others, he said.

Self-deception is even more important in maintaining the cohesiveness of society, the cultural glue that binds humans together in the service of value, virtue and meaning. “Culture is by definition self-deceptive,” according to Sussman. “But it is essential for human existence,” especially for pro-social or altruistic behavior.

“We need something all humans can believe in,” said Goodenough, some benevolent “suspension of disbelief.” In short, humans need Rue’s noble lie.

Concluded Rue: “If they are noble lies, and if they are beautiful and well told, then they will overwhelm our detection systems and make us say--as we do whenever we encounter a dandy piece of magic--’I should know better, but damn , that was convincing.’ ”