Aluminum Bat Cuts Cost, Raises Averages : It’s Cheaper Than Wood, but Those Line Drives Can Be Dangerous

Cruise by any baseball field where college, high school or youth teams play and you’re bound to hear it. Ping . Sometimes it comes in staccato bursts. Ping . Ping. The sound is unmistakable.

It’s Metal Madness.

Just as the electric guitar forever changed the sound of popular music and the way it is played, the aluminum bat has done the same to baseball. Amateur baseball players have been cracking, uh, pinging out hits and home runs for more than a dozen years.

The aluminum revolution was fueled by the bats’ cost-saving durability and the added punch they seem to give batters. Coaches also like the bats--typically much lighter than a wood bat of similar length--because they have helped produce more offense, thereby increasing interest in the game.

But not everybody loves them. Some say their added punch, which has given new meaning to the term line drive , makes the game unsafe for pitchers and infielders. Professional baseball, as anti-metal as John Denver, has always used wood and may never switch. And baseball purists always have thought that aluminum bats should simply be canned.

Just recently, two fellows named Mays and McCovey recycled the ruckus that initially was raised when the bats were introduced in the early ‘70s. Their comments about metal’s deleterious effect on the grand old game gave aluminum advocates a slight case of the willies.

The former sluggers, with 1,181 career home runs between them, said that the use of aluminum bats at the amateur level has helped to reduce the number of power hitters in professional baseball. Their theory is, once a player gets to all-wood pro ball, he still longs for the light feel of aluminum and ends up using a wood bat that not only lacks ping but also pop.

Whether that is true depends on who you talk to. And just about everyone involved with baseball has a thing or two to say about aluminum bats.

“The development of offensive baseball has been sensational,” said Bob Hiegert, who coached at Cal State Northridge for 18 years and produced two Division II national championships. “The aluminum bat revolutionized the college game because you have men playing with a weapon that is much more productive than wood.”

Said former USC and 1984 Olympic Coach Rod Dedeaux: “The aluminum bat drastically alters the game. It’s not the game of baseball as we would like to think of it.”

Ray Poitivent, who has scouted for 28 years and is a special assistant to General Manager Harry Dalton of the Milwaukee Brewers, is philosophical in discussing the impact of the aluminum bat.

“You just can’t change the game and think it’s going to be the same.”

Baseball hasn’t been the same since the NCAA Baseball Rules Committee approved aluminum bats and the designated-hitter for the 1974 season. At that time, college baseball was suffering from dwindling attendance at the College World Series in Omaha, the dominance of a few teams and a perceived lack of offense.

USC and Arizona State had won nine of the previous 10 Division I national championships, including eight straight. USC won the title again in 1974, but no college team since has repeated as champion.

Some say it is more than coincidence that parity and the aluminum bat arrived at the same time, but other factors are more obvious. The NCAA has limited the number of athletic scholarships, which helped to disperse talent. Professional teams also began drafting more players from the collegiate ranks, making college programs more attractive to high school players who traditionally opted for the pros right away.

Still, there can be no discounting the impact aluminum bats have had on the college game.

Baseball America magazine conducted a study and found that the overall batting average for Division I schools increased from .282 in 1976 to .293 in 1980 to .306 in 1985. Home-run production was up 70% in the nine-year period.

Hiegert offers his own study as evidence of the bats’ impact.

In 1970, before aluminum bats were used, CSUN won the Division II championship with a team that played 64 games, batted .269, hit 32 home runs and had a 2.59 earned-run average. The Matadors won the title again in 1984. This time, using aluminum, they played 65 games, batted .327, hit 71 homers and had a 4.58 ERA.

“You can say players have gotten better, or one team was a better offensive team than the other, but that wasn’t necessarily true with those teams,” said Hiegert, now CSUN’s athletic director. “We had two All-Americans on each club and the same amount of players that signed pro contracts. They played on the same field with the same dimensions. One team used wood and the other used aluminum. It’s not a mystery to me.”

Some observers blame a livelier baseball and a lack of talented pitchers for the offensive explosion. However, an experiment in a semipro league suggests otherwise. During the past two years, college players in the Cape Cod, Mass., summer league used wood bats that were bought by the league with a $10,000 subsidy from major league baseball. Batting averages dropped 28 points, home-run production dropped 38% and one run was knocked off the cumulative league ERA.

The evidence suggests that wood bats bring pitching and defense back into the picture and make for a more balanced game. But for high school and college coaches who work on limited budgets, the most important balance is in their program’s checking account.

“You’re talking to a purist, a sentimentalist, all those things,” said Arizona Coach Jerry Kindall, whose team won the national championship in 1986. “I am against the aluminum bat in theory and ideology--but I have to account for my budget.”

The eight teams in the Atlantic Coast Conference experimented with laminated wood bats last fall but decided to scrap them for the regular season. North Carolina Coach Mike Roberts estimates that it would cost between $3,000 and $4,000 to outfit a Division I baseball team with enough wood bats to last an entire season. In contrast, he said, it costs just $500 to $1,000 to supply a team with aluminum and the money left over can be used for other things.

“High school and college baseball are not income-producing sports at most schools,” UCLA Coach Gary Adams said. “Ninety-five percent of the baseball programs in the country do not make money--they cost money.”

The savings are even more pronounced at the high school level. Before aluminum, Birmingham Coach Wayne Sink said a high school team routinely could go through as many as 12 dozen bats a season. Sink said he hasn’t purchased an aluminum bat since the early ‘70s because his players buy their own and use them for three to four years. Canoga Park Coach Doug MacKenzie said his players do the same. Granada Hills Coach Darryl Stroh said he buys just a few bats each year for use during practice.

The purist’s attitude is reflected in what political columnist George Will had to say about the durability of aluminum bats: “Immortality is not a virtue in things that should not exist at all.”

Measuring monetary savings is relatively easier and a lot less controversial than measuring the difference in distance a ball travels off aluminum and wood bats. In 1977, researchers at Stanford University compared wood and aluminum bats of similar weight and balance and found no significant proof that the ball traveled farther off either material. But it’s difficult to convince everyone of that fact.

“In most cases, the home runs that come out of high school and college fool you,” Poitivent said. “The aluminum bat gives everyone added strength.”

He said a player such as Texas Rangers’ outfielder Pete Incaviglia, who holds the NCAA single-season home-run record with 48, has strength, period. “That’s why it doesn’t matter whether he uses wood or aluminum. With wood, he gets it out of the park. With aluminum he hits the ball nine miles.”

Cleveland Indians’ outfielder Cory Snyder disagrees. Snyder, who played at Canyon High, finished his three-year college career at Brigham Young with 73 home runs and hit a ball on top of the roof at Comiskey Park in Chicago during an exhibition game before the 1984 Olympics. When he got to pro ball--and wood bats--he continued to hit for average and power. Last year, after being recalled in June from Triple-A, Snyder hit 24 home runs in just 103 games.

“The ball jumps off the bat a lot quicker with aluminum,” Snyder said. “But if you hit the ball right in the sweet spot with a wood bat, it’s going to go just as far.”

The sweet spot, according to researchers, is the area of a bat with which a hitter will get the best transfer of power from the collision of bat against ball. Upon impact, the ball travels farther and faster than if the ball is hit with any other part of the bat.

The problem, as some coaches and scouts see it, is that an aluminum bat has more sweet spots than a wood bat of similar length.

“I remember hitting the ball on the nose,” said Moorpark College Coach Ron Stillwell, who played at USC from 1959 to 1961. “With the aluminum bat, the whole thing is the nose.”

A 34-inch, 34-ounce wood bat has a sweet spot located 6 1/2 to 8 1/2 inches from the end of barrel and measures about the width of a baseball. A 34-inch aluminum bat--which can weigh as little as 29 1/2 ounces--has a sweet spot of similar width, but because the bat is tapered differently, the batter is able to take advantage of a hitting surface almost twice as large.

That is why the average right-handed high school and college batter is able to fight off an inside fastball and double off the outfield wall. With a wood bat, he would have nubbed a grounder and broken the bat.

“It can make scouting very difficult,” Chicago White Sox scout Craig Wallenbrock said. “You can go see a guy who gets four hits in a game and he may not have hit the ball hard once. I’ve seen kids who are 5-6, 140 pounds hit the ball over a fence 400 feet away.”

The headaches suffered by scouts are tame compared to the pain some pitchers have felt, courtesy of aluminum-aided line drives. The NCAA does not keep statistics on bat-related injuries, but coaches and scouts say more and more pitchers are being struck because they are unable to react quickly enough to balls hit back through the box.

“An aluminum bat can be dangerous,” said Cal Poly Pomona Coach John Scolinos, whose teams have won three Division II national championships. “Pitchers can’t jam hitters using aluminum bats. So, a ball thrown out over the plate is being hit right back at the pitcher and there is no time to field the ball or get out of the way.”

In February, Pepperdine pitcher Tony Lewis was struck in the face with a line drive while pitching against USC. The ball crushed many of the bones on the right side of Lewis’ face, including his eye socket. Lewis underwent extensive surgery and made his first pitching appearance since the injury a few weeks ago.

In March, Dave Eberhardt was pitching for the University of Buffalo in a game against Duke when he was hit in the side of the head by a line drive. Eberhardt fell to the ground with blood pouring from his right ear and was admitted to the Duke Medical Center with a fractured skull.

“As he was falling down, he yelled, ‘Somebody help me, I don’t want to die,’ ” Duke Coach Larry Smith said. “There are people who will say similar injuries have occurred with wood bats, and that is true. But, I think the chances of that happening are much slimmer than with a metal bat.”

In 1985, Arizona pitcher Mike Young, who had played at Rolling Hills High, was considered a top professional prospect when he was struck in the face by a line drive at Stanford. The ball shattered Young’s cheekbone--and his confidence. He never pitched effectively in college again but is attempting a comeback in professional baseball with the San Diego Padres organization.

“When you pitch against hitters with aluminum bats your whole life, you don’t realize that you really can’t see the ball come off the bat,” said Young, who is playing for the Padres’ Single-A affiliate in Charleston, S.C. “In high school and at the JC level, it’s not as bad. But in major college, the players are two years older and they hit the ball that much harder.

“I haven’t had any problems in pro ball, yet. But I know what happened to me is going to happen again this year to another college pitcher. I guess it’s going to have to happen a few more times until they realize it’s dangerous.”

Said Hiegert: “The pitchers and corner people cannot react quickly enough. They’re getting close to the limit.”

The heaviest hitter in the baseball-bat business is Van Nuys-based Easton Aluminum Inc. The company, which produces as many as 30,000 bats a week, has an estimated 90% market share of sales of competitive hardball bats.

Hillerich & Bradsby of Louisville, Ky.; Worth Bat Co. in Tullahoma, Tenn., and St. Louis-based Rawlings Sporting Goods Co. all take their swings at Easton, but all strike out in terms of sales clout.

“Easton was the first company to come out with an aluminum bat that feels like wood going through the hitting zone,” said Florida State Coach Mike Martin, whose team finished second in the nation last year. “Everyone else is trying to catch up. I don’t know how much difference there is between the different companies’ bats, but people have had success with Easton and you’re not going to mess with success.”

Easton got into the bat-making business in the ‘70s after the company’s initial venture into sporting goods as an arrow manufacturer. Easton also makes bicycle tubing, windsurfing products and hockey sticks.

A privately held company, Easton does not divulge financial data. In a Times story four years ago, 1982 sales reportedly were between $25 million and $40 million. Since then, the company has doubled in size, and profits aren’t far behind, according to product manager Ed Wholley.

“We’re in the technology business,” Wholley said. “What we’ve done is take technology and translate it into the sporting goods business. We do a lot of field testing and lab testing. And before we even think about the design of a particular bat, we sit down and discuss alloys and properties.”

Easton keeps its aluminum process confidential and machines its own manufacturing equipment rather than let an outside company do the work.

Hillerich & Bradsby, a 103-year-old company that makes the trademark Louisville Slugger and supplies most of the wood bats used in professional baseball, has felt the impact of the aluminum onslaught. Fifteen years ago, before aluminum came into vogue, Hillerich & Bradsby was the king of swing, selling 6 million wood and about 50,000 aluminum bats.

This year, the company will sell 1.5 million wood and more than 500,000 aluminum bats.

“We could see the handwriting on the wall,” said Bill Williams, vice president of advertising for H & B. “Ten years ago we were a little dubious. We weren’t resistant to aluminum, but we didn’t want to put all of our eggs in one basket.

“Now, we’re constantly doing battle with Easton. The success is in the laboratories.”

At the Hillerich & Bradsby lab in Louisville, the company tests its products for hardness, strength and bending. The company also uses a cannon pitching machine that fires the ball at as much as 200 m.p.h. at a stationary bat. Another machine simulates the swing of a bat against a stationary ball. Williams said the company gets information about new metals from the aircraft and space industries.

Easton, too, has its high-tech testing methods, but Wholley maintains that the company’s secret to success is its manufacturing equipment, some of which is so confidential that the company prohibits cameras in certain areas of the plant.

How did we get to this point of space-age research and applications? After all it’s only a game, right?

CSUN’s Hiegert remembers the days aluminum bats arrived on the scene in their most primitive form. Back in 1965, when Hiegert began coaching at Northridge, most of his after-practice time consisted of nailing and taping together the wood bats that had broken or split that day.

In the late ‘60s, Wilson Sporting Goods introduced a bat called the Indestructo, which was 35 inches long and weighed 38 ounces. The bat never broke--thereby living up to its name--but it was unusable in game situations because of its weight.

Easton, which was making bats for Adirondack at the time, brought models out to CSUN for testing during the early ‘70s.

“If you had a 35-inch metal bat, it weighed at least 35 ounces,” Hiegert said. “Then you started to get a 34-34 in the Thumper model that Worth put out. The mid-’70s is when I really started to notice a difference in the performance of the bat.”

In order to curb the growing offensive explosion in college baseball, the NCAA Baseball Committee issued a statement last November urging bat manufacturers to pursue development of non-wood bats that feature the performance characteristics of wood bats but do not produce a greater hit distance. The committee also said that commencing in 1988, new non-wood bats that represent a significant design change must be presented to the committee for approval.

“There are more metal alloys coming on the market and we want to make sure we’re at least touching bases with the manufacturers, so we’re not supporting a ‘super bat,’ ” said Bob Hannah, baseball coach at the University of Delaware and the chairman of the committee.

“Aluminum is the main one right now, but there are other space-age metals being worked on in these labs,” he said. “I’m not sure what the future is--maybe a mixture. Our whole thrust, though, is to have manufacturers continue working toward a product that, in performance, resembles wood.”

The manufacturers welcome the feedback from the NCAA. But, like the teams that they supply, they’re out to win their own game.

“As an industry, our comment to them is, ‘That’s fine,’ ” Williams said. “We’re in the business to make a profit and we’re going to do whatever we can to beat our opponents. One of the most interesting comments I hear is, ‘Make it more like wood.’ Consequently, we have received no clear-cut direction.”

Looming on the horizon for the late ‘80s and ‘90s is the graphite bat. The Worth Co. field-tested its model during major league spring training camps and has submitted the bat to the NCAA committee for approval.

“We feel it’s a good compromise,” said Doug Bennett, sales manager for Worth. “Graphite combines the best characteristics of wood and aluminum. It has a closer feel and sound to wood and it’s durable like aluminum.”

Brian York, who coaches at North Hollywood High, was scouting for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1981 and remembers the day he ventured onto the field at Dodger Stadium before a game between the Dodgers and the Phillies.

“Pete Rose was with the Phillies back then and someone handed him an old-style Easton,” York said. “Now, Rose is not a home-run hitter, but I saw him put five or six balls into the seats like a rocket. On the high school level it’s fine, on the college level it’s OK, but on the pro level I have serious reservations.”

Even with the advent of artificial playing surfaces, the designated-hitter and other innovations, many observers doubt that aluminum will ever find its way into tradition-steeped professional baseball.

Pro scouts say it’s difficult to judge a player’s mettle when he’s swinging metal and that the adjustment to the wood bat in the pros is often a frustrating or futile experience.

“It takes us 30 minutes of instruction to introduce them to wood,” Poitivent said. “We have to explain how to use it or they’d be breaking 40 bats the first day.”

Said Giants’ scout George Genovese: “Some of them cannot adjust and they lose their confidence.”

Scouts use former Florida State slugger Jeff Ledbetter as an example of the transition difficulty. In 1982, Ledbetter hit a then-NCAA record 42 home runs. Ledbetter, 6-3, 215 pounds, could not duplicate those statistics in the minor leagues and never got past Double-A with the Boston Red Sox and St. Louis Cardinals organizations.

“I was never really a big home-run hitter to begin with,” Ledbetter said. “I just had the strength and the aluminum bat was tailor-made for me. In college, I hit a lot of line-drive home runs. I think that hurt me in the minor leagues because I still had it in my mind that I should be able to do that with wood.”

Players who have avoided the side effects of aluminumitis and become converts to wood now favor white ash over whiffle-bat weighted metal.

Snyder said using a wood bat makes him more selective at the plate. “You can’t swing and get good contact on pitches low and away or up and in like you do with aluminum,” he said.

Former Kennedy High catcher Phil Lombardi, who opened this season at Triple-A Columbus in the New York Yankees’ farm system, said it often can be a physical adjustment.

“You’re real conscious of using wood at first, especially if you start a season in a cold-weather city and pitchers are busting you in on the hands,” he said. “But I’ll tell you this, there is nothing like hitting a baseball square off a wooden bat.”

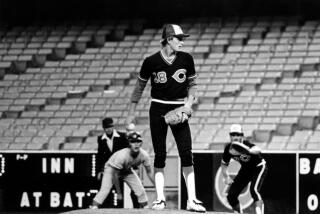

Cincinnati Reds’ infielder Kurt Stillwell, formerly of Thousand Oaks High, remembered his first game using wood at Billings, Mont., in the Pioneer Rookie League.

“I tried to find a wood bat that was similar to the Easton I had used in high school,” Stillwell said. “I got four hits my first game, so it didn’t take me long to adjust.

“I don’t like the sound of the ping anymore.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.