Apocalypse Future: Joining the Insanity

The other night I watched the evening news companioned by my two youngest boys--ages 8 and 9--who were excitedly and prematurely in place for the Academy Awards--an annual childrenâs show in which Hollywood recklessly uncurtains the fusion of the mercenary with the meretricious from which cinematic alchemy distills its illusions. And so, in an accident of scheduling, we watched together something that was no illusion at all: the intermittent detonation of warfare in the Gulf of Sidra.

The encounter with Libya was, to my jaded eyes, no more surprising, no less inevitable than the selection, later that night, of âOut of Africaâ--an inoffensive, effulgently photographed sentimentalization of a sparse, painfully detached memoir--as the best film.

We had sent our ships into the gulf, as was our right. Kadafi shot at us, as we had anticipated. We shot back, as we had to do. Just another skirmish in the 40 yearsâ war that began when Harry Truman sent the Navy in 1946 to scare the Soviets out of Iran.

Reflecting thus, I was interrupted by the strangely strained voice of my 8-year-old. âDaddy,â he asked, âis there going to be a war?â I looked. Both sons were tensed, slightly frightened, the ebullience gone. âOf course not,â I answered, âthereâs not going to be any war.â They relaxed, reassured by the possessor of all wisdom, and returned to marking their choices on the Academy Award ballot thoughtfully provided by our local tabloid.

I saw no great moral issue in the Libyan confrontation. Unable to prevent the terrorist harassments spawned in that ugly little land, we had, like a frustrated pachyderm assaulted by a swarm of black flies, bellowed our defiance over the bordering sea. A warning, a threat or a bluff? Time would tell.

But what I did not see myself, I perceived through the eyes of children. It was nothing of special relevance to this particular incident, but the very hue and substance of the world that they had so recently inherited. Somehow, through the pleasant order of this affluent Massachusetts town that had cocooned their entire existence, past the amiable shopkeepers, a placidly embanked Sudbury River and the clean-mown Little League fields, the insanity of the world had penetrated and had taught them to be afraid.

The images that we watched were not contrived, but palpable, material substance: the whine of warplanes, explosions, flame and, somewhere hidden from sight--the dominant image of our most violent century--the torn remnants of other men.

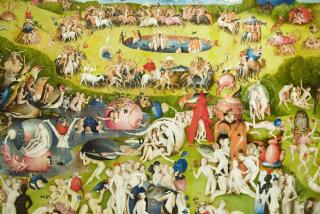

Right or wrong, wise or foolish, the scene was not a pleasant one, testifying as it did to the ineradicable savagery of man, the unsleeping appetites that have made ours the most destructive century in the history of the planet Earth, as well as--I hesitate to write, lest it be only self-deception--the first era to bear the possibility that man might tame himself.

The difference, and the only source of hope, is not in ourselves but in invention of a force so great that its use will destroy the destroyers.

In just nine years half a century will have passed since Hiroshima was demolished. It has not been a peaceful time. Yet there is little doubt that the existence of nuclear weapons--and that alone--has kept us from tumbling into a third world war.

That restraining fear is the bright side of scienceâs darkest gift. But it is beginning to dim. Two generations have come to maturity in a world whose existence is in peril. We lack the psychological tools to understand what price that buried apprehension has cost us--a society fragmented at every level, adrift from established values, uncertain and confused of conviction. Most dangerously, our natural response to unbearable possibility has gradually numbed our sense of dread, worn away the urgency of our awareness that these weapons must be eliminated, that we cannot live with them forever, that men are fully capable of the insanity leading to their use.

In another generation almost no living person will remember a time without the Bomb. Universal adaptation to co-existence with unimaginable possibilities will bring us to the moment of irretrievable danger. We already have a government with no interest in arms control, either because it does not believe in it or because it views every proposal as a Soviet trick. Meanwhile, an old and fading President mindlessly invokes the rhetorical blusters of a less destructive age, as if he could resurrect dead simplicities by repeating them.

Still, failure to topple the monster that we have raised is not the fault of government. It is my fault. And yours. It is the fault of people everywhere who have lost the vitality to insist that these weapons be taken from our own untrustworthy hands--not for the sake of peace but for survival, whose desire is as deeply rooted as our instinct for destruction.

The capacity for wise fear still lives. My children proved that. But its time is growing short. I know that many have voiced similar warnings in past decades, only to have their apocalyptic prophecies disproved. But this time it is true. Once we have become accustomed to insanity, we will--all of us--become part of it.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.