What happens when humans confront a form of nature with no rational order?

- Share via

Book Review

Absolution: A Southern Reach Novel

By Jeff VanderMeer

MCD: 464 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In the 18th century, mathematical concepts of rationalism were used by scientists and thinkers to impose order on chaos. In the disparate fields of biology and literature, intellectuals reached back to Latin to fashion new words such as “genus” and “genre.” In “Absolution,” Jeff VanderMeer has written a book that defies stultified notions of literary genre to lure readers into a form of nature in which no rational order can be imposed.

“Absolution” is the surprise fourth installment of VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy published in 2014, which comprises “Annihilation,” “Authority” and “Acceptance.” But the book stands alone and can be read that way, or as both prologue and denouement in which mysteries previously left unresolved will continue into the future.

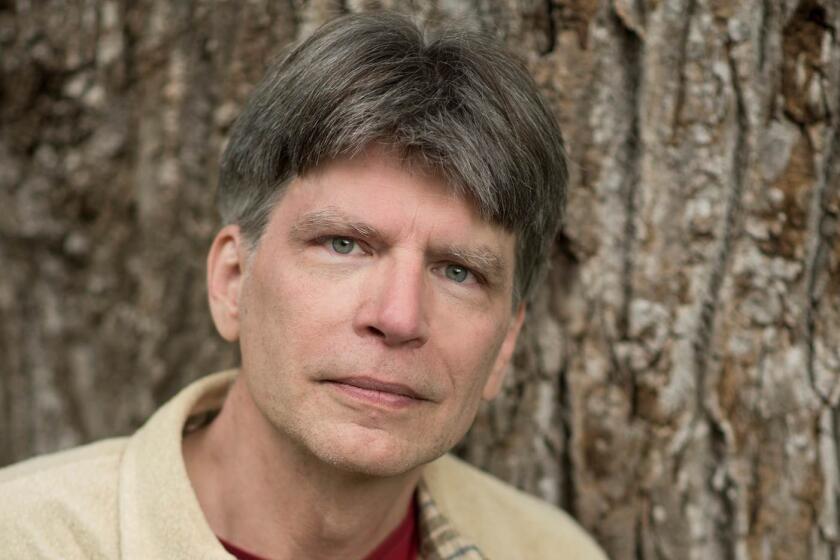

VanderMeer is a gifted writer. He uses his beautiful prose — sometimes muscular, sometimes lyrical — in service to his brand of ecological-horror science fiction that asks probing questions of human nature.

“Absolution” is broken into three parts. The first fills in some of the prehistory of Area X, where the trilogy was set. It’s the story of the first mission sent to the Forgotten Coast, biologists equipped with various scientific tools to map out an area where nature has escaped known categories.

I’m making a conscious effort to not reveal unnecessary spoilers, but in the first few pages, the narrator informs his audience that “most of the locals had always seen the government as an invading hydra,” that had sent these “uncanny” biologists to meddle in something they shouldn’t.

These scientists carry an unwanted burden: mysterious creatures that are the result of a hybrid of flesh and technology. The novel’s structure tells these hybrid creations’ past, present and future. In Western ways of thinking, the “monster” is a mixture of form, often interpreted as immoral and revolting. But what if what we regard as unnatural is a form of nature, one in which no adaptation can be judged by human classifications of artificiality or the natural order?

‘Playground’ is an intricately braided novel of overlapping love stories and unresolved polarities that doesn’t always come to three-dimensional life.

As events play out across the book, detectives appear, at some moments, as intrepid explorers sent to conquer murderous life forms that alter human flesh. These modern-day conquistadors engage in page-turning, edge-of-your-seat battles with terrifying hobgoblins who want to destroy them in dreadful ways. Much more terrifying than destruction at the hands of familiar weapons, these creatures threaten to disrupt our notions of beginning and ending by dissolving human forms, to consume the species and make them into something else.

Another type of detective appears in the form of Old Jim, the alias of a man no longer sure of his own name. He appears first as the chronicler of those early disastrous forays into Area X. Later in the book, his mission is to solve the great mystery that will provide explanations for the past and present. But he’s also a spy whose efforts are subverted by those who do not want his revelations to become public.

The solving of a mystery relies not only on the sequencing of events and the facts of the case, but on making a judgment about motivation that will determine innocence or criminality. VanderMeer posits that these are not the means that will be useful in talking about nature.

As Earth’s human inhabitants confront the ways nature has responded to human interference through rising global temperatures, those events repeatedly get interpreted as the punishment of human beings by “the destruction of the earth.”

In her latest short story collection, Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez offers haunting imagery and a sharp focus on mental, physical and economic ruin.

It is no such thing. The Earth will continue as a planet, and what comes next will be nature’s evolving state devoid of familiar categories. We seem to be terrified by that great unknown.

The nature contained in Area X has been seen either as nature in its mythical untouched form, a paradise instantly spoiled by our presence, or as the future of a punishing deadly hell that rebukes humanity for its hubris. VanderMeer confounds any of these views, and for good measure, disrupts another human illusion. Time, in “Absolution,” is a state of change and movement, despite human attempts to track it with calendars and quantify its passage. And it’s certainly not an inevitable journey toward progress.

Some readers may anticipate that “Absolution” will answer all the plot mysteries of the Southern Reach series. Well … “abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” VanderMeer doesn’t write to unscramble characters’ conundrums or point the future in an implied trajectory. This is not a book I would recommend for readers who want solid ground beneath their feet.

Readers willing to forgo such conventions are in for a treat. Several times in my own reading, I thought I had stumbled on a narrative trail. At one point in the work, I thought I recognized religious allegories told as the eternal struggle between good and evil, and human punishment told in the mad ravings of a prophet. At another moment, I felt the gothic horror of Mary Shelley’s monster set free in a Lovecraftian world (without the racism.). Or the book might be a logical dissembling of paranoid conspiracy theories that dog our current political moment. But I discarded these ideas and more as I read.

‘Cli-fi’ is a growing genre as drought, blizzards, heat waves and wildfires reshape our lives. But it doesn’t have to be dystopian.

I finally let my need to figure out what was coming fade, and let myself glory in the feelings evoked in different scenes. What I needed to do was observe details, notice the writer’s world as it was presented in vivid prose or follow the labyrinth of a character’s thoughts as they sought to interpret their experiences.

Letting myself occupy VanderMeer’s world reminded me of what it would feel like to wander the canvas of the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch. How the humans in “The Garden of Earthly Delights” look comfortable with the chaos they’re a part of, and how that same world of chaos is dark and terrifying in “The Last Judgment.” VanderMeer writes of how grief for what has changed echoes in us even as we welcome newness. And there were times when I felt that deep sadness, a mourning of the dissolution of what we’ve considered normal.

The solutions to the great mysteries of life, VanderMeer implies, are the results of earlier decisions that were made about the methods we would use to analyze them. They are the consequences of the series of accidents and mistakes that are a natural result of existing as a creature that will never be perfect. In “Absolution,” those methods and expectations are useless. The mystery is whether human beings can discard our worn-out tools and rusty armor and enter into chaos naked, but not afraid.

Lorraine Berry is a writer and critic living in Oregon.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.