Fertility rates fall, but global population explosion goes on

Global birthrates are falling. But with many in their fertile years and political and cultural forces against contraception, the population explosion is far from over.

- Share via

Mamta, left, and Ramjee Lal Kumhar. The rate of global population growth will largely be determined by their generation, the largest in history. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

July 22, 2012

First of five parts

JAIPUR, India — Ramjee Lal Kumhar and his bride, Mamta, first laid eyes on each other inside a billowing wedding tent festooned with garlands of marigolds.

He was 11 years old. She was 10.

Their families had arranged the marriage. The couple delighted their parents by producing a son when they were both 13. They had a daughter 2½ years later. To support the family, Ramjee gave up his dream of finishing school and opened a cramped shop that sells snacks, tea and tobacco on the muddy road through his village.

At 15 and finally able to grow a mustache, Ramjee made a startling announcement: He was done having children.

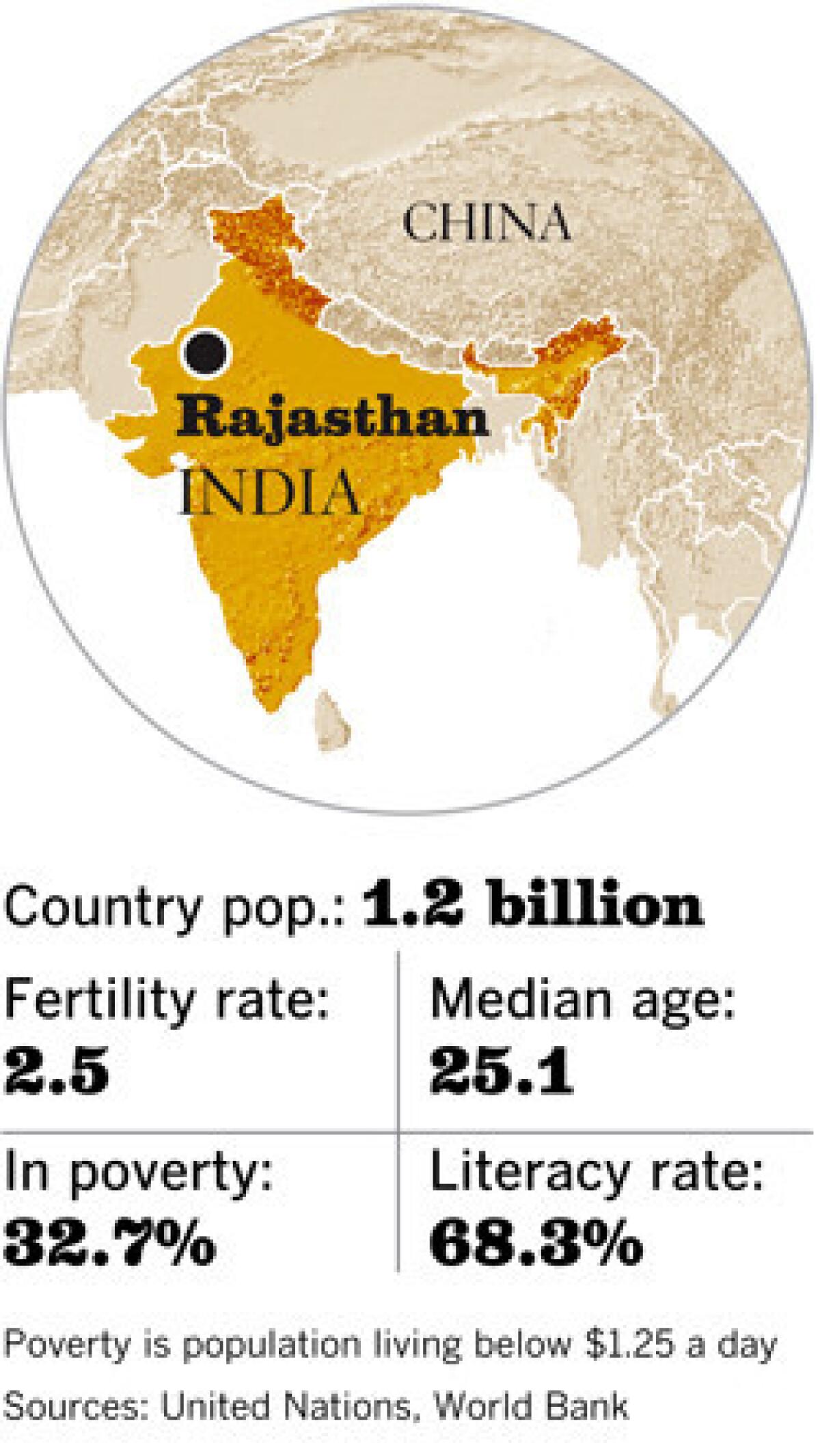

"We cannot afford it," he said, standing with arms crossed in the dirt courtyard of the compound he shares with 12 relatives, a cow, several goats and some chickens in the northern state of Rajasthan.

Horrified, his mother and grandmother pleaded with him to reconsider.

"Having one son is like having one eye," his grandmother said. "You need two eyes."

How many children to have is an intensely personal matter, often a source of family debate. But the decisions made by Ramjee, Mamta and others their age will have repercussions far beyond their own families and villages.

They are members of the largest generation in history — more than 3 billion people worldwide under the age of 25. About 1.2 billion of them are adolescents just entering their reproductive years.

If they choose, collectively, to have smaller families than their elders did, the world's population — now 7 billion — will continue to grow, but more slowly.

According to United Nations projections, the number will rise to 9.3 billion by 2050 — the equivalent of adding another India and China to the world.

That's an optimistic scenario, one that assumes the worldwide average birthrate, now 2.5 children per woman, will decline to 2.1.

If birthrates stay where they are, the population is expected to reach 11 billion by midcentury — akin to adding three Chinas.

Under either forecast, scientists say, living conditions are likely to be bleak for much of humanity. Water, food and arable land will be more scarce, cities more crowded and hunger more widespread.

On a planet with 11 billion people, however, all those problems will be worse.

The outcome hinges on the cumulative decisions of hundreds of millions of young people around the globe.

The relentless growth in population might seem paradoxical given that the world's average birthrate has been slowly falling for decades. Humanity's numbers continue to climb because of what scientists call population momentum.

So many people are now in their prime reproductive years — the result of unchecked fertility in decades past, coupled with reduced child mortality — that even modest rates of childbearing yield huge increases.

"We're still adding more than 70 million people to the planet every year — which we have been doing since the 1970s," said John Bongaarts, a leading demographer and vice president of the nonprofit Population Council in New York. "We're still in the steep part of the curve."

Think of population growth as a speeding train. When the engineer applies the brakes, the train doesn't stop immediately. Momentum propels it forward a considerable distance before it finally comes to a halt.

U.N. demographers once believed the train would stop around 2075. Now they say world population will continue growing into the next century.

In India, a country of 1.2 billion people, women have an average of 2.5 children each, and the birthrate is projected to fall to 2.1 by 2030. At that point, parents will merely be replacing themselves.

But even then, India's population will continue to grow because of momentum. It is on track to surpass China's and is not expected to peak until 2060, at 1.7 billion people.

Momentum isn't the only factor in population growth. In some of the poorest parts of the world, fertility rates remain high, driven by tradition, religion, the inferior status of women and limited access to contraception.

Population will rise most rapidly in places least able to handle it: developing nations where hunger, political instability and environmental degradation are already pervasive.

The African continent is expected to double in population by the middle of this century, adding 1 billion people despite the ravages of AIDS and malnutrition.

Even under optimistic assumptions, the toll on people and the planet will be severe.

How we got to 7 billion

How we got to 7 billion

Today, about 1 in 8 people in the world lives in a slum. By midcentury, with the population at more than 9 billion, the ratio would be 1 in 3, assuming poverty and migration to cities continue at their current rates.

Now nearly 1 billion people are chronically hungry, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, and at least 8 million die every year of hunger-related illnesses.

By midcentury, there will be at least 2 billion more mouths to feed, and no one can say where the food will come from.

It's not just that the population will be larger. It's that hundreds of millions of newly affluent people, mostly in Asia, will want to add dairy products and grain-fed beef and pork to their diets.

To meet the projected demand, the world's farmers will have to double their crop production, according to calculations by a team of scientists led by David Tilman, a University of Minnesota expert on global agriculture.

William G. Lesher, a former chief economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, said the brightest minds in the field haven't figured out the solution.

"We're going to have to produce more food in the next 40 years than we have the last 10,000," he said. "Some people say we'll just add more land or more water. But we're not going to do much of either."

We are doing the best we can. These slums are increasing day by day.”— Anup Murari Rajan of CARE India

Most of Earth's best farmland has already come under hoof or plow, and farmers are losing ground to expanding cities and deserts. Soil erosion, chemical contamination and salt buildup from irrigation are despoiling prime acreage.

Climate change will make all of these challenges more daunting. Higher temperatures and violent weather will stunt or destroy crops. Increased flooding will imperil millions living in low-lying regions. More severe droughts could displace masses of people, leading to conflict.

By 2050, the United Nations predicts, there could be as many as 200 million "climate refugees."

Despite these trends, population growth has all but vanished from public discourse.

In Europe, Japan and North America, leaders are worried about having too few young people to care for aging populations and to fund benefits for the elderly.

In developing countries, leaders often consider large youthful populations a source of economic vitality and political strength.

In the U.S., contraception has become entangled in acrimonious battles over abortion, causing some environmental and humanitarian groups to retreat from family planning initiatives.

Under the best conditions, it's hard to get contraceptives into the hands of impoverished women who want them. In developing nations, family planning programs open and close at the whim of autocrats. Aid from wealthy nations rises and falls with political currents.

The result: Nearly 20 years after 179 nations signed a pledge to provide universal access to family planning, supplies of contraceptives remain erratic in much of the developing world.

Population growth gets less attention than it did in the late 1960s, when there were half as many people on the planet.

Children listen as they await a midday meal at a community center on the outskirts of Lucknow. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

In a shantytown outside Lucknow, India, 350 miles east of where Ramjee and Mamta live, dozens of half-clad children sing and play at a community center.

Their giggles and shrieks give way to silence when a large steel pot of porridge arrives.

As they take their seats on strips of burlap, their eyes follow a wrinkled woman in a flowing orange-and-white sari who ladles rice and lentils into metal bowls. When everyone has been served, they dig in greedily — some with spoons, some with fingers.

A 10-year-old boy watches intently from a distance, his clothes draped on a scarecrow frame. He brought a younger sister for the midday meal, provided by the nonprofit CARE India for children ages 2 to 6.

He mouths the metal rim of an extra bowl he brought along just in case there is anything left over.

There isn't.

As the preschoolers head home, the boy trails his sister, the clean bowl dangling from his fingertips.

Although India's population growth has slowed among the urban middle class, birthrates remain high among the rural poor.

The result, especially in northern states like Uttar Pradesh, is a scramble to fill each bowl.

"We are doing the best we can," said Anup Murari Rajan, an officer with CARE India, which provides free meals at 32,000 community centers in Uttar Pradesh. "These slums are increasing day by day."

A decade ago, the state had 166 million people. Today it has 200 million — more than Brazil. If Uttar Pradesh were a country, it would be the fifth-most populous in the world.

Fertility has been declining slowly, but women in the state still have 3.5 children each on average.

At this pace, Uttar Pradesh's population will double by midcentury.

Reducing population growth in India's poor northern regions would require an extensive push to make contraceptives widely available in scattered villages and rural areas, many of which lack paved roads or clinics.

Women are desperate for family planning services, to take control of their lives.”— Gopi Gopalakrishnan, of the nonprofit World Health Partners

Government efforts have been haphazard and limited, reflecting an ambivalence about family planning. A national law restricts women under 18 from marrying, but the tradition is so strong and enforcement so lax that nearly half do so anyway, all but guaranteeing an early start to childbearing.

In wooing foreign investors, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh speaks of India's "ample human resources ... a growing working-age population in a world that is aging very rapidly." India's leaders view their country's youth bulge as a competitive advantage over China, whose workforce is older because of long-standing restrictions on family size.

"India doesn't want to reduce its fertility because they say they don't want to have China's aging problem," said Hania Zlotnik, former director of the U.N. Population Division. "But most of their growth is in the poor. Is it a good thing to have a larger number of poor people in your population?"

In the absence of a strong government commitment to family planning, nonprofit groups struggle to make a difference.

Using start-up funds from an anonymous U.S. donor, World Health Partners in New Delhi tries to make contraceptives affordable by negotiating hard with manufacturers to obtain low-cost supplies.

It buys mainly intrauterine devices, or IUDs, for 66 cents apiece and sells them for 77 cents to franchise clinics, which can charge their customers a bit more to make a small profit.

At a clinic in Muzaffarnagar, 70 miles north of New Delhi, more than 100 young women lined up in the dim hallway and spilled out the door. More sat surrounded by young children on the roof, a makeshift waiting room complete with plastic chairs.

They had come for a once-a-month distribution of IUDs. Each patient took a pregnancy test, had a pelvic exam and was fitted with the contraceptive device. The price per patient: $3.29. Those with government cards showing they lived below the poverty line paid $1.76.

The turnout was so large that dozens of women were told to come back the next day.

"Women are desperate for family planning services, to take control of their lives," said Gopi Gopalakrishnan, president of World Health Partners.

Surveys have found that nearly a quarter of women of childbearing age in Uttar Pradesh do not use modern contraception, even though they want to avoid pregnancy. Many women in rural areas cannot travel to health centers or afford contraceptives.

World Health Partners' clinics in Uttar Pradesh serve 1,000 villages, home to about 3.2 million people. Gopalakrishnan plans to expand the network to 20,000 villages with 50 million people — barely one-fourth the population of this one state.

In neighboring Bihar, India's poorest state, Gopalakrishnan recalled that he once helped transport doctors, nurses and equipment to a tent clinic, prepared to surgically sterilize 200 women.

Ten times that many showed up.

"When it became clear we couldn't register them all, they broke all of the furniture and chased the doctors away," he said. "These were all women. Muslim women — with a desperate need."

Population momentum

Population momentum

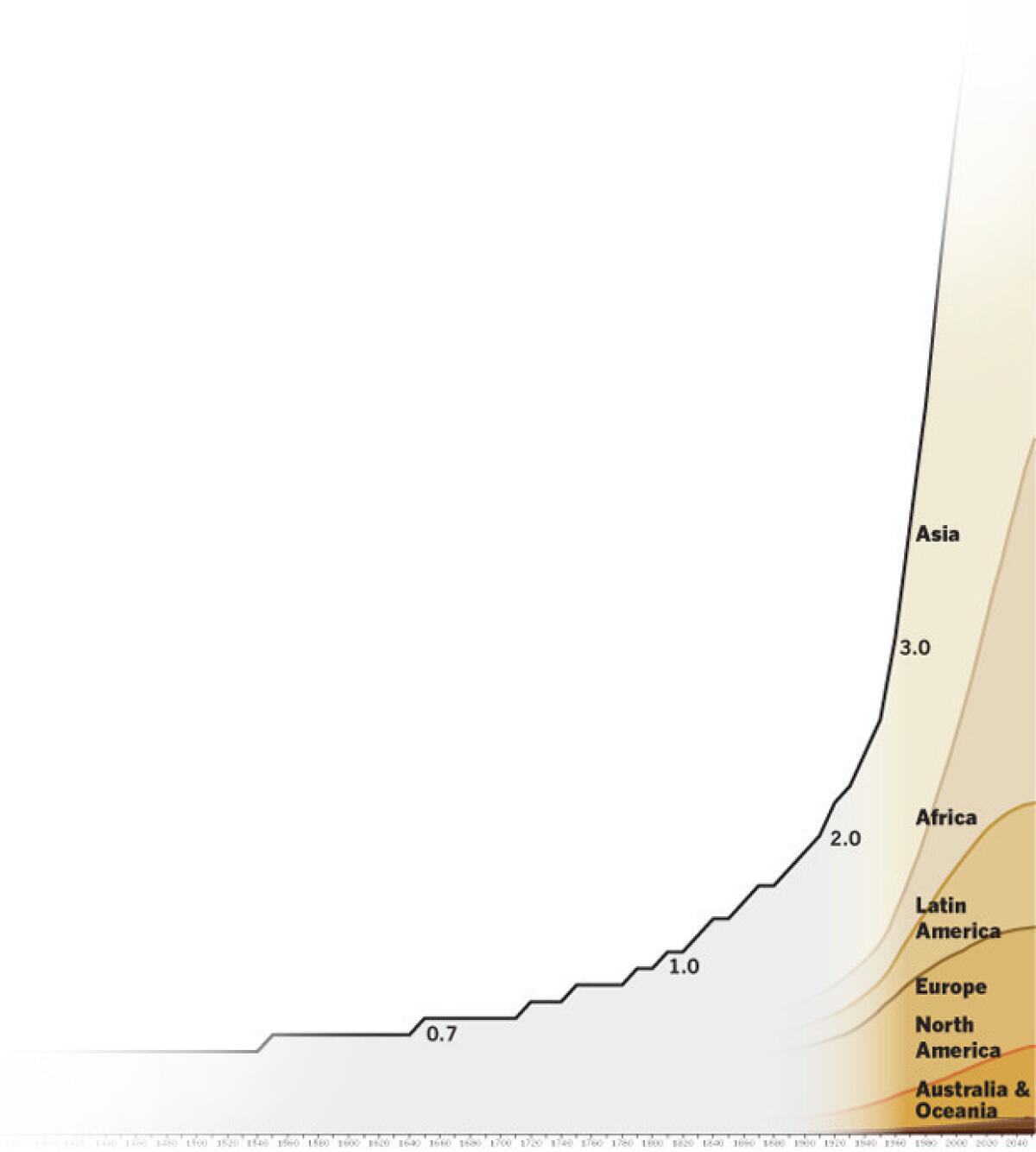

Population is rising sharply as the largest generation in history comes into its childbearing years.

For most of human history, the world's population grew very slowly. Short life spans and high child mortality offset high birthrates.

Advances in agriculture, followed by the Industrial Revolution, pushed humanity to the 1-billion mark around 1810. From there, the numbers began a steep ascent.

With improved sanitation, more reliable food supplies, vaccines and other medical advances, the population doubled to 2 billion by 1930 and doubled again by 1974.

Last year, the global population passed 7 billion. It took just a dozen years to add the last billion.

The precipitous rise has not resulted in famine, disease and other catastrophes on the scale famously forecast by Thomas Robert Malthus in 1798 and by Paul Ehrlich in the 1968 bestseller "The Population Bomb."

Malthus did not foresee that mass migration to the New World would relieve population pressures. Ehrlich didn't anticipate the success of the Green Revolution — modern, intensive farming methods that boosted crop yields.

Still, the warnings of Ehrlich and others helped inspire a population control movement. As the pill and other modern contraceptives cut birthrates in industrialized countries, environmental groups, the World Bank and a succession of U.S. presidential administrations joined in a robust campaign to bring family planning to the developing world.

The effort soon ran into a powerful counterforce: the antiabortion movement. Its activists sought to halt U.S. aid to family planning programs abroad, pointing to abuses such as forced abortions and sterilizations in India and China.

In a notable success, lobbyist Steven W. Mosher helped persuade the administration of President George W. Bush to withhold $34 million to $40 million a year over seven years from the U.N. Population Fund, the largest international donor to family planning programs.

U.S. foreign health aid should be spent saving lives, "not preventing them coming into being," Mosher said in an interview. Like some others in the antiabortion movement, he considers many forms of contraception "chemical abortion" because they prevent embryos from implanting in the womb.

The funding was later restored, but many advocates of family planning have retreated, recast their missions or reduced their profiles.

The Rockefeller Foundation, once a leading philanthropic supporter of international family planning, sharply cut back its funding in the late 1990s. Other donors have stepped forward, including the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, named for the late wife of investor Warren Buffett, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The broad picture is one of erratic funding and unpredictable political crosscurrents. Both have made it difficult for governments and advocates in developing countries to maintain, let alone expand, access to contraception.

U.S. funding for family planning overseas has been flat in inflation-adjusted terms for two decades. Such aid to poor countries from all sources, measured per-capita, has been declining since 1999.

The result: Although use of contraceptives worldwide has climbed steadily in the last 40 years, led by the industrialized West and China, it remains extraordinarily low in the least developed parts of Africa and South Asia.

In Nigeria, for example, about 8% of reproductive-age women who are married or in relationships use contraception, compared with 72% in the United States. By some projections, Nigeria will surpass the U.S. as the third-most-populous country by midcentury.

Stabilizing the world's population will require reducing birthrates in such countries. Yet many of them are hard to reach, culturally unreceptive or politically unstable.

For supporters of family planning, they are the last frontier.

Francisca Kanyari had two children by age 20, and her husband had six others with another wife, in a country where polygamy is legal. Kanyari believed she and her two boys would be better off if she stopped having children. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

A muddy road in Kibera, Kenya's largest slum, overflows with humanity. Women tote buckets of water on their heads and bundles of firewood on their backs. Young men splash through open sewers in bare feet.

A century ago, this was grazing land and acacia forest. Now it is a hive of mud huts with rusting metal roofs. Hundreds of thousands of people, mostly migrants from the countryside, are packed into a 500-acre area of Nairobi that reeks of sweat, human waste and rotting garbage.

With no running water or plumbing, the area is notorious for "flying toilets" — plastic bags of feces tossed into muddy alleyways. There are regular outbreaks of cholera, typhoid and dysentery.

Tucked behind mud walls is a family planning clinic operated by Marie Stopes International, a British nonprofit.

Inside, a row of chairs sits empty beneath a single bare light bulb.

"We ran out of stock some time ago," said Esther Omariba, a clinic nurse. "When we have adequate supplies, word gets around really fast and many, many women come."

Across Africa, clinics in impoverished or remote areas run out of contraceptives so often they have a term for it: "stockouts."

Kenya's family planning program was once held up as a model on the continent. In the late 1970s, the government joined with international donors in a high-profile effort that reduced the birthrate from more than eight per woman to fewer than five by the late 1990s.

Then Kenya was shaken by political turbulence, and a Republican-controlled U.S. Congress slashed family planning budgets. Supplies of contraceptives were interrupted across the East African nation and the decline in the birthrate stalled.

A decade ago, the U.N. predicted that Kenya's population would reach 44 million by 2050. Now the figure is expected to be nearly 100 million.

Even when contraceptives are available, many women face opposition from their husbands, in-laws or traditional leaders.

At 20, Francisca Kanyari already had two children and her husband wanted more. He had six other children by another wife, common in a country where polygamy is legal. He supported both households on one salary.

Kanyari believed she and her two boys would be better off if she stopped having babies. So every three months, she sneaked away from her thatch-roof hut in northern Kenya to visit a clinic and receive an injection of the hormonal contraceptive Depo-Provera.

"With Depo," she said, "no one sees it. And I'm free."

Covert contraception programs have emerged throughout Africa. Some are mobile, including camel caravans that serve semi-nomadic Samburu women in northern Kenya. Others operate out of doctors' offices in major cities.

Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, director of the U.N. Population Fund, said women used to come to him on the sly for contraceptives when he was practicing medicine in Lagos, Nigeria, begging him to keep it private.

"Most had several children," he said. "These are intelligent women who want to give their children a fighting chance for a better life."

Even when a young husband sees the advantages of a smaller family, the pressures to have many children can be intense.

When Ramjee Lal Kumhar became a father for the first time at 13, he was delighted to hear the doctor announce: "Congratulations. You've got a son."

By producing a male heir, he had fulfilled his most important family obligation. In Hindu culture, sons care for parents in their old age and perform last rites at funerals — seen as crucial to opening a pathway to heaven.

His wife, Mamta, became pregnant again two years later, just as Ramjee's sundries shop was starting to make a little money.

"Suddenly I had a huge responsibility," said Ramjee, a thoughtful young man who mulls over questions before answering.

He had given up his dream of going to college and becoming a police officer. But he wanted more for his children and was worried about the cost of feeding, clothing and educating them. It would be best, he thought, if he and Mamta stopped at two children.

His announcement filled the household with tension, which was heightened when Mamta gave birth to a girl.

Ramjee's mother and his grandmother insisted that the couple have at least one more son in case something happened to their firstborn.

"The child is very weak," said his mother, Laxmi Devi Kumhar, depositing the 2-year-old boy in Mamta's lap.

Ramjee responded: "If you don't allow this, there will be an added burden on me and my family.... How can I progress in my life?"

As those around her squabbled, Mamta cooked over a stove fueled by cow dung, swept the courtyard with a tree branch and scrubbed the open-air latrine.

The daughter of a family in a nearby village, she had been forced to quit school before the sixth grade and was lent to an ailing aunt to do household chores.

She has conformed to her new family and accepted her place. Posing for a family portrait, she squatted low to make sure her head was below those of her mother-in-law, grandmother-in-law and any man.

Asked her views on the family debate, she deferred to Ramjee or said little, pulling her head scarf tight across her mouth and biting into the yellow fabric.

A day came when Ramjee decided it was time to act.

He knew condoms were not foolproof. Birth control pills and IUDs were too expensive or unavailable in the village. Surgical sterilization, on the other hand, is widely practiced in India and subsidized by the government. Ramjee considered a vasectomy but feared complications.

After talking with his 15-year-old wife, he drove her on his father's motorbike to a hospital 25 miles away. Mamta's yellow-and-orange sari fluttered in the wind as they weaved around camel-drawn carts and water buffalo.

At the hospital, a doctor tied her Fallopian tubes.

Ramjee's mother has now pinned her hopes on her younger sons, ages 10 to 15.

"I need at least two grandsons out of every one of my five other sons," she said.

"Ten or 15 more sons will be a healthy sign."

Times staff photographer Rick Loomis contributed to this report.

About the series

Los Angeles Times staff writer Kenneth R. Weiss and staff photographer Rick Loomis traveled across Africa and Asia to document the causes and consequences of rapid population growth. They visited Kenya, Uganda, China, the Philippines, India, Afghanistan and other countries.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.