The battle for Mosul: How to free 1 million residents without killing them

- Share via

Reporting from Debaga Camp, Iraq — Omar Turki defied Islamic State and fled the city of Mosul on foot last month with his family of five, the youngest just 6 months old.

Eager to escape the coming battle to free the city from the militant group’s violent grip, the family had to cross a trench — apparently designed to be filled with oil and set ablaze to foil the would-be liberators — and walk through a minefield.

Now living in a large camp set up by international aid workers 40 miles southeast of Mosul, Turki, 26, has been phoning relatives back home and warning them that, when Iraqi troops arrive for their assault, Islamic State militants will be merciless.

“I told my family when the Iraqi army comes, just go to them so Islamic State don’t use them as human shields,” said Turki.

Turki’s perilous journey is about to be replicated by thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, as a coordinated assault by Iraqi and Kurdish forces begins on Iraq’s second-largest city. Key to any success in reclaiming the city is ensuring the safety of up to 1.2 million civilians, the largest population of any urban battle so far in Iraq’s war against Islamic State.

Military commanders have urged civilians to shelter in their homes while the battle rages. U.S. B-52 bombers have dropped as many as 7 million leaflets around the city instructing civilians to tape over their windows in the shape of an X to keep them from shattering, disconnect gas pipes, hide valuables and stay low near the floor.

“Tell your children that the loud booms are just thunder,” the leaflets advise.

Already, 1,900 people have fled to camps in Iraq and 900 more to similar facilities in Syria, aid workers say. That tally will probably rise to 200,000 in the first two weeks of the offensive, whose initial operations began this week, and could reach 1 million by the time the operation concludes.

The Iraqi government has said safe routes will be set up to help civilians evacuate, but local aid workers say they have not been informed of the plans.

“In Fallujah, there were passages that were said to be safe and they weren’t. We don’t want that to happen,” said Karl Schembri, spokesman for the Norwegian Refugee Council, which is operating in northern Iraq.

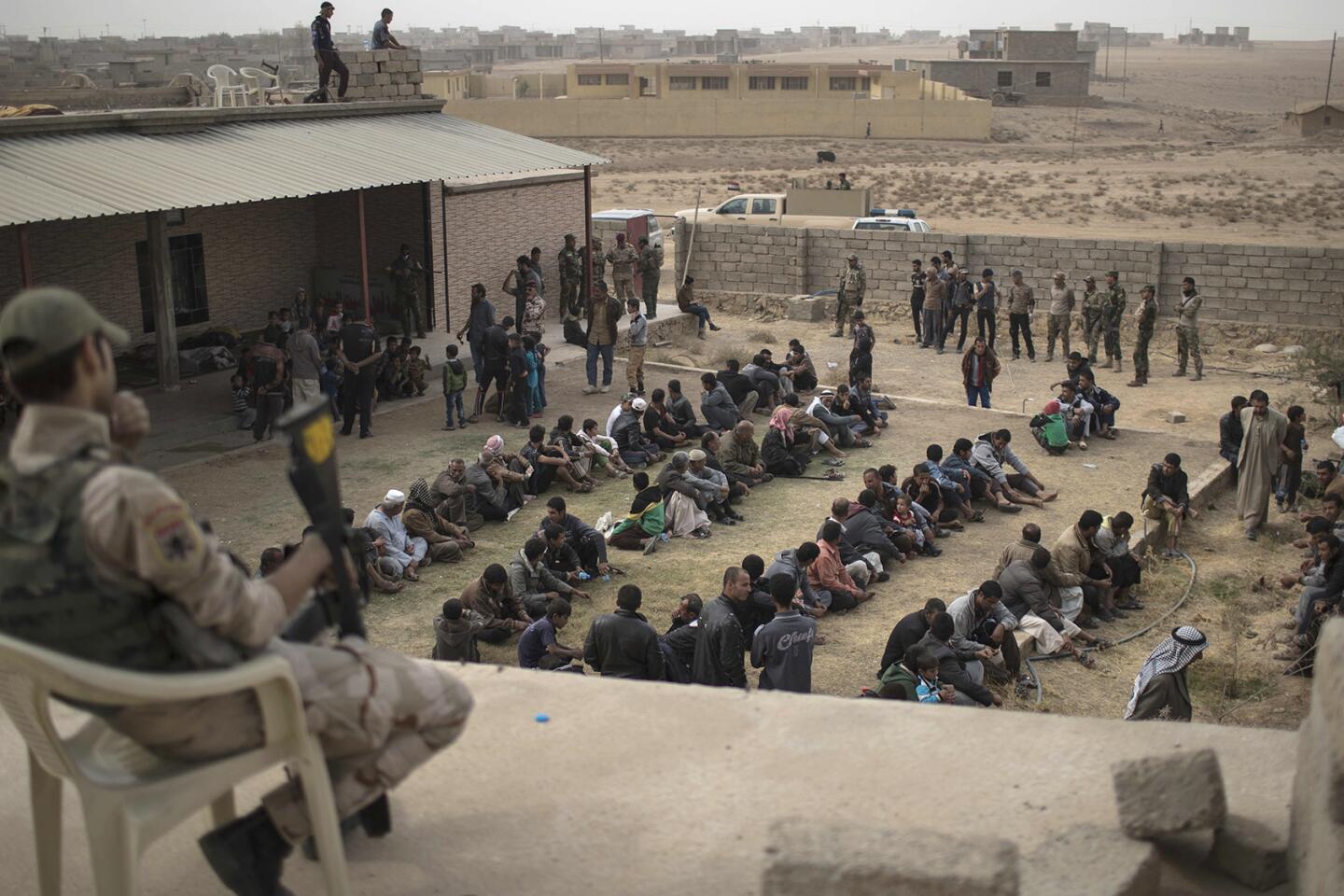

Iraqi authorities faced criticism after the offensive over the summer in Fallujah, in western Iraq, for failing to protect, screen and funnel civilians through safe paths to temporary housing.

A dozen men and boys were shot and killed outside Fallujah after surrendering to men who had appeared to be friendly because they were wearing military and federal police uniforms; 73 other men and boys from the same tribe are still missing, according to an Amnesty International report released Tuesday.

In Saqlawiya, near Fallujah, militiamen seized about 1,300 men and youths, then transferred 600 to local officials days later bearing signs of torture, according to the report, based on interviews with more than 470 former detainees, witnesses and relatives of those detained, missing or killed.

“Fallujah has very important lessons that everyone should have learned from,” said Schembri.

“The problem here is that the magnitude of this crisis — the number of people, where they can flee to, where they can go to — is huge,” he said. “We’re talking about 1.2 million people, as opposed to the 84,000 in Fallujah.”

Humanitarian aid workers have no way of knowing whether it’s best to advise Mosul’s residents to stay in their homes or flee — only they can know that, as the battle unfolds, and those who elect to remain could eventually run out of supplies, Schembri said.

“It’s a very bleak dilemma, whether to risk to stay or risk their lives leaving, so there’s nothing to be confident about, [and] the longer this takes, the more desperate their situation will become,” he added.

Prime Minister Haider Abadi said at a briefing that he had not read the Amnesty International report about the problems in Fallujah but that Iraq has “zero tolerance toward human rights violations.”

“The situation in Fallujah wasn’t really functioning, but those lessons have been incorporated, and we trust they will be upheld so that those who choose to flee can do so” from Mosul, he said. “If we do not uphold the protection of civilians, we risk rekindling the issues that brought [Islamic State] here in the first place.”

Another difficulty is how to detect Islamic State fighters among the civilians who flee the city.

Some militant leaders have left Mosul ahead of the Iraqi offensive, but foreign fighters, who might be more easily recognized, appear to be staying, according to Maj. Gen. Gary J. Volesky, commander of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

“They’re not going to be able to exfiltrate as easily as some of the local fighters or the local leadership,” Volesky told reporters on a teleconference call from Baghdad. “It’s difficult for them to blend into the local population.”

In Fallujah, he said, some militants dressed as women to escape. “That didn’t work for them.”

U.N. authorities are establishing 11 camps in the area to house as many as 120,000 people, but officials say they hope they won’t see that many leave Mosul.

“The more civilians will feel protected inside Mosul, the less they will be displaced,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said in a visit to the Debaga camp this week. “For those who feel they have to go because it is dangerous, also they have to be treated with dignity and respect.”

The camp was built for 20,000 people, but is already housing 31,700, including 655 displaced in the last two days.

There are scores of cinder-block shacks and tents. Newly arrived men sleep in the mosque, women and children in the school. Camp workers try to keep it clean, but the sheer volume of new arrivals – many with young children - has left the floors dirty and strewn with garbage. Rice and beans were served Wednesday, but many people said they were still hungry and thirsty.

“Even in the zoo it’s better than this,” said a man who asked to be identified as Abu Mahmoud, 41.

The father of four, who teaches at a trade school, paid a team of armed smugglers $400 to get his family out of Islamic State-dominated Hawija to the south last week. They survived Islamic State mines and sniper fire, he said, unlike a group of neighbors captured the same day, or a cousin killed by a mine while attempting the same journey two weeks ago.

Thousands more are paying smugglers even steeper prices to flee west from Mosul into Syria.

About 5,000 displaced people have fled from the Mosul area during the last two weeks to the Hol camp in northeast Syria. The camp was built to house 7,500 but currently is holding 10,000, according to Tarik Kadir, Mosul response team leader for the nonprofit Save the Children. He said 3,500 other people displaced from Mosul are waiting to enter at the Syrian border.

Kadir said those fleeing paid smugglers an average of $2,500. “It’s only those who have money who are getting out,” he said.

Inside Mosul, preparations for the coming battle appear to be vigorously underway, according to residents who have fled, many of whom remain in communication with family members inside.

Some Islamic State fighters have been broadcasting a call to arms for an impending holy war, and have moved into churches and mosques, apparently to avoid being targeted by airstrikes, Turki said.

He said residents have been forced to shut off lights and generators at night, also to avoid airstrikes. Those caught with cellphones are killed.

Turki said many residents, including his wife’s family, have tried to move east across the Tigris River, where it might be easier to flee, but housing is scarce. Islamic State fighters recently fanned out across the west side and threatened to kill those caught moving, Turki said. Last month, he said, a smuggler who had helped families move was hanged.

A woman who identified herself only as Um Menhal, interviewed at the Debaga camp, said Islamic State fighters this week were hiding in homes as the offensive advanced, and attempted to use her family and about two dozen others in their village south of Mosul as human shields before they managed to escape.

She said her two brothers, both former police officers, have remained in Mosul and plan to join the fight to liberate the city. But they have only a couple hours of electricity every few days, and have gone days without bread.

Um Iyad, 27, fled Mosul to a nearby village in June, then came to the Debaga camp two months ago with her four sons. She left behind her husband, a driver unwilling to part with a car he wouldn’t be able to drive past Islamic State fighters. He’s now living amid mortar attacks and airstrikes without water, electricity or fuel oil, she said.

Her parents have also remained, stockpiling food. “My mom told us, ‘I won’t flee from here. If I die, I will die in my house,’” she said.

When she last visited her parents and siblings in Mosul three months ago, Islamic State fighters had moved into their neighborhood, holing up in abandoned buildings.

A slight figure in a tattered red gown embroidered with black flowers, Um Iyad was having trouble sleeping, constantly contemplating the fate of her city. Above the black veil that covered her face, her eyes filled with tears.

“I am so worried,” she said.

Times staff writer Hennessy-Fiske reported from Debaga camp and special correspondent Bulos from Irbil, Iraq. Times staff writer W.J. Hennigan in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.