Why America Has Waged a Losing Battle on Fallouja

- Share via

FALLOUJA, Iraq — As soon as the women of Fallouja learned that four Americans had been killed, their bodies mutilated, burned and strung up from a bridge, they knew a terrible battle was coming.

They filled their bathtubs and buckets with water. They bought sacks of rice and lentils. They considered that they might soon die.

“When we heard the news,” said Turkiya Abid, 62, a mother of 15, “we began to say the Shahada,” the Muslim profession of faith.

There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the messenger of God.

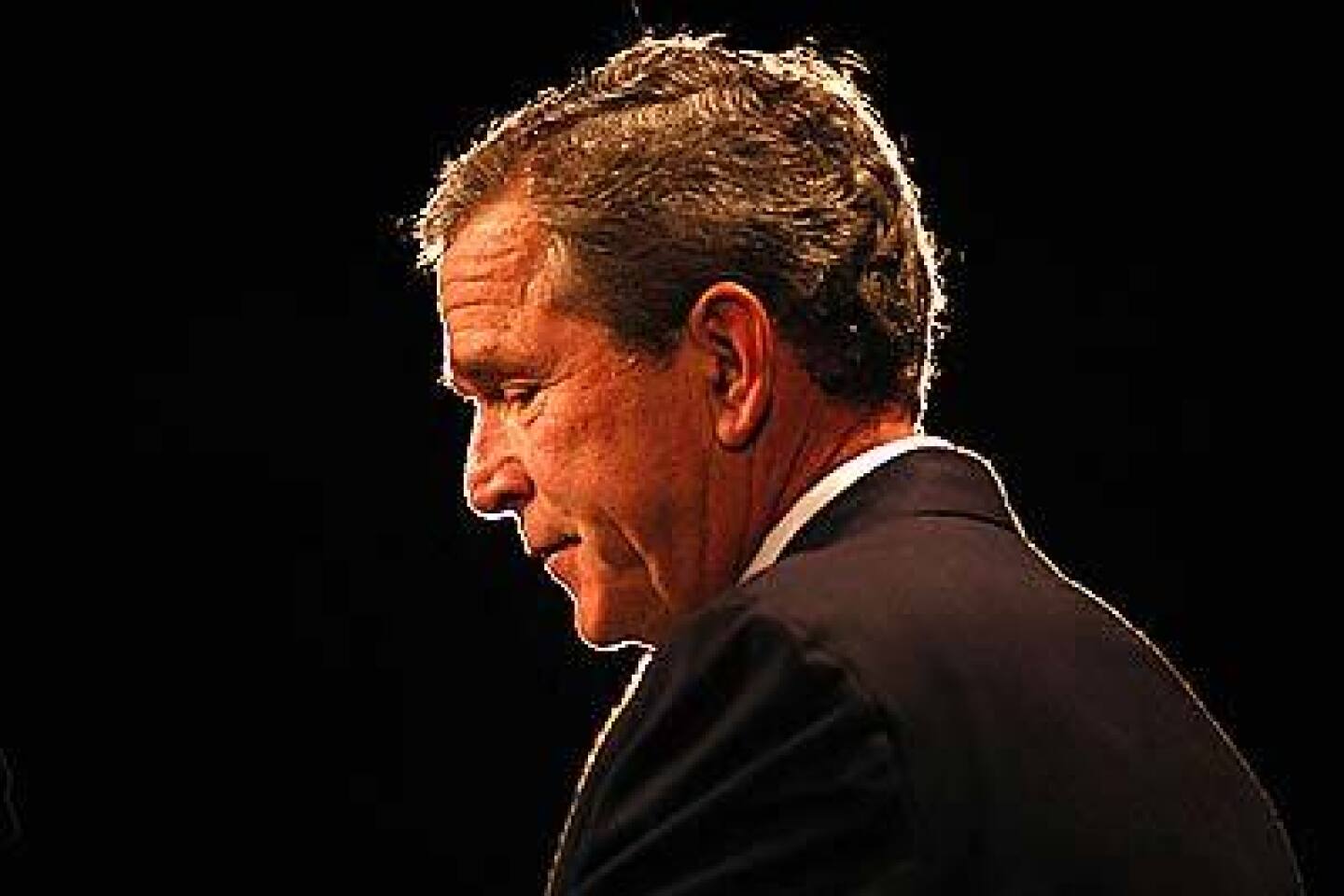

In Washington, the reaction to the March 31 killings was exactly what the women of Fallouja had expected: anger. Those inside George W. Bush’s White House believed that the atrocity demanded a forceful response, that the United States could not sit still when its citizens were murdered.

President Bush summoned his secretary of Defense, Donald H. Rumsfeld, and the commander of his forces in the Middle East, Army Gen. John P. Abizaid, to ask what they recommended.

Rumsfeld and Abizaid were ready with an answer, one official said: “a specific and overwhelming attack” to seize Fallouja. That was what Bush was hoping to hear, an aide said later.

What the president was not told was that the Marines on the ground sharply disagreed with a full-blown assault on the city.

“We felt that we ought to let the situation settle before we appeared to be attacking out of revenge,” the Marines’ commander, Lt. Gen. James T. Conway, said later.

Conway passed this up the chain — all the way to Rumsfeld, an official said. But Rumsfeld and his top advisors didn’t agree, and didn’t present the idea to the president.

“If you’re going to threaten the use of force, at some point you’re going to have to demonstrate your willingness to actually use force,” Pentagon spokesman Lawrence Di Rita said later.

Bush approved the attack immediately.

That was the first of several decisions that turned Fallouja from a troublesome, little-known city on the edge of Iraq’s western desert to an embodiment of almost everything that has gone wrong for the United States in Iraq.

Just as they had previously, U.S. policymakers underestimated the hostility in Fallouja toward the American military occupation of their land.

The U.S. assault on the city had the unintended effect of fanning the Sunni Muslim insurgency, precisely the outcome the United States wanted to avoid.

U.S. officials ignored the risk that American military tactics and inevitable civilian casualties would undermine support for the occupation from allies in Iraq and around the world.

Although military and civilian authorities eventually agreed on the Fallouja assault, their consensus quickly broke down, leading to hasty and improvised decisions.

The insurgency in Fallouja was never going to be easy to quash, but disarray among American policymakers contributed to U.S. failure.

This account is based on interviews with more than 40 key figures, many of whom refused to be identified because they still hold military or government jobs.

The troubles began with Bush’s authorization to attack Fallouja, based on the sole option Rumsfeld and Abizaid gave him.

After the president ordered the Marines to advance, they battled their way into the city against heavy resistance. Four days later, with Fallouja only half-taken, they were abruptly ordered to stop.

The problem was not military but political: Members of the Iraqi Governing Council were threatening to resign, and British Prime Minister Tony Blair and United Nations envoy Lakhdar Brahimi had appealed to Washington to halt the offensive.

Before pulling out of Fallouja, the Marines hurriedly assembled a local force called the Fallouja Brigade, which they said would keep the insurgents in check. It proved an utter failure. Many of the men who enlisted turned out to be insurgents.

But it took nearly five months for the Marines and the new Iraqi government to disband the brigade. In the meantime, under the brigade’s watch, Fallouja became a haven for anti-American guerrillas, a base for suicide bombers, and a headquarters for the man U.S. officials consider the most dangerous terrorist in Iraq, Abu Musab Zarqawi.

“Fallouja exports violence,” said Col. Jerry L. Durrant, one of the Marine officers who inherited the problem.

Today the United States finds itself back where it started in April. Securing Iraq requires solving the problem of Fallouja. The U.S. military is bombing targets in the city almost every day, but few military analysts believe that will get the job done. A major offensive, perhaps the most significant battle of the unfinished Iraq war, is likely after the U.S. presidential election.

As they were in April, the Marines are poised on the outskirts of the city, awaiting orders.

*

Part I

GOING IN

Fallouja lies in the province of Al Anbar, which stretches west from the outskirts of Baghdad to the Jordanian border, south almost to the ruins of ancient Babylon and north to Salahuddin, the province that includes former President Saddam Hussein’s hometown of Tikrit. It also borders Saudi Arabia and Syria.Dominated by Sunni Muslims, Al Anbar is a landscape of shifting sands and mercurial allegiances. Unemployment has always been a problem. Fallouja, one of its largest cities, is deeply tribal, conservative and suspicious of outsiders.

Hussein, himself a Sunni, dealt with the province by drawing on its men for his army, Republican Guard and intelligence service.

When the war came, however, they did not fight for him.

Realistic about Iraq’s military inferiority, they followed the instructions of U.S. special operations forces, who had scattered leaflets telling them that if they stayed home, they would not be attacked — and they weren’t.

But when troops of the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division occupied a school in the center of the city shortly after Baghdad fell in April 2003, Falloujans did not take it well. A rumor circulated that the soldiers were using their night-vision goggles to see through the clothes of women in the city.

Five days after the soldiers moved in, a protest demanding that they leave turned violent. Seventeen Falloujans were killed and 70 injured in the clash with troops.

Soon after, L. Paul Bremer III, the newly appointed civilian administrator for the U.S.-led Coalition Provisional Authority, dissolved the Iraqi army, along with the intelligence service, the Republican Guard and half a dozen other security services that had worked for Hussein. Overnight, thousands of men in Al Anbar lost their jobs and their pensions. It was a humiliation to them.

Skirmishes continued in Fallouja throughout the next year, even after U.S. troops moved their camps outside the city limits.

By last March, the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force had replaced the Army there. The Marines brought with them a minimal-force strategy, restricting their reprisals to targeted strikes while offering help in the form of money and aid.

But the violence did not end. On March 27, at least four Falloujans died in a confrontation with Marines in an industrial neighborhood on the city’s north side.

It was into that landscape that four Americans working as private security guards made a wrong turn into the city on the morning of March 31.

Only a few yards in, they were halted by a barrage of bullets. A home video showed one contractor lying face down as a crowd surged around his sport utility vehicle. He appeared to have gotten the vehicle’s door open, and he stumbled out, dying of gunshot wounds.

The mob set the SUV on fire. Two of the contractors’ burned bodies were taken to a nearby bridge and suspended, looking like blackened rag dolls. The mob cheered.

Most Americans, including many working in Iraq, were stunned by the fury — the willingness not just to kill but also to mutilate. Many Iraqis also were horrified. A young Baghdad native who went to Fallouja reported with disbelief that adolescent boys were carrying pieces of charred human flesh on sticks “as if they were lollipops.”

Among U.S. military officials in Iraq, the first response was to take a deep breath. The comments from spokesman Brig. Gen. Mark Kimmitt were surprisingly measured given the barbarity that was being rebroadcast every 15 minutes.

“There often are small outbursts of violence. They will go in, they will restore order and they’ll put those people back in their place,” he said of the Marines.

A day later, Brig. Gen. John Kelly, assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division, told a reporter that he would not be pushed into a counterproductive siege. The Marines would confront the insurgents, make friends with moderates in the city and gather intelligence.

The Marines would also search for Iraqis who could be leaders in Al Anbar. At Camp Pendleton in California, they had studied the problems other military units had encountered in the province and had concluded that the only authority the fiercely anti-Western residents would accept was that of local leaders. The difficulty was finding some who were also acceptable to the Americans.

Kimmitt reiterated the Marines’ position. “We are not going to rush pell-mell into the city,” he said.

*

U.S. RESPONSE

At Bremer’s headquarters in Hussein’s mammoth Republican Palace in Baghdad, and in Bush’s Oval Office in Washington, the conversation started from a different premise. The slayings of the U.S. contractors were a challenge to America’s resolve.Bush issued a statement reaffirming his determination to defeat the insurgents. “We will not be intimidated,” Press Secretary Scott McClellan quoted the president as saying. “We will finish the job.”

Bremer’s response was more emotional. At a graduation ceremony at Iraq’s new police academy, he called the killers in Fallouja “human jackals” and the battle for the town part of a “struggle between human dignity and barbarism.” The deaths of the security guards, he promised, would “not go unpunished.”

Conway, the commander of the Marines in western Iraq, told the overall commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, Army Lt. Gen. Ricardo S. Sanchez, what the Marines had in mind.

According to one well-placed defense official, Conway also told Rumsfeld directly that the Marines favored a deliberate approach. But Rumsfeld rejected his advice. The Defense secretary and Air Force Gen. Richard B. Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, believed that “it was unsatisfactory to have parts of the country that were not under control,” Pentagon spokesman Di Rita said.

A civilian official who declined to be identified said that “the military leadership told us this was something they could do with a low risk of civilian casualties, using their precision weapons.”

It was on April 1 that Rumsfeld and Abizaid briefed Bush on plans for attacking Fallouja. Rumsfeld’s decision not to inform the president about the Marines’ dissenting recommendation was proper, Di Rita said. That argument had been settled at a lower level.

“Military commanders owe their military advice to each other. The secretary and the chairman owe their military advice to the president,” the spokesman said. “It is true that there was not a united view.”

In a matter of hours, the president’s decision made its way to the Marines at their desert outpost eight time zones away. At Camp Fallouja, the command post outside the city, Sanchez told Conway and his aides: “The president knows this is going to be bloody. He accepts that,” an officer recalled.

Conway was perturbed. He expressed his reservations in front of the other staff officers — a way of making sure his objections were on the record.

But Col. John Coleman, Conway’s right-hand man, who was present at most of the meetings, said that in the end, the Marines’ job is to follow orders. “When the president says we go, we go.”

On April 2, the Marines began preparing their attack, named Operation Valiant Resolve. Initially, the Marines estimated that they would need two battalions, a total of 2,500 troops, and that the mission would take 10 days. The fighting was plotted down to the street level. One battalion would take the northern half of the city, another the southern, and they would meet in the middle.

The Marines knew the stakes were high. “This battle is going to have far-reaching effects on not only the war here in Iraq, but in the overall war on terrorism,” one young officer wrote home.

But beyond the declaration that the goal was to kill or capture those responsible for the contractors’ deaths, there was no clear definition of the endgame. No one explained what, at the end of the day, the U.S. would have won.

“First prize, a week in Fallouja. Second prize, two weeks in Fallouja,” a U.S. diplomat working with the occupation authority in Baghdad said dryly.

On April 4, Maj. Gen. James N. Mattis, commander of the 1st Marine Division, whose units would carry the battle, summoned his commanders to a final briefing.

The general, known as “Mad Dog Mattis” to his men, made it clear that the Marines were now in warrior mode.

“You know my rules for a gunfight?” he asked a reporter outside the meeting. “Bring a gun, bring two guns, bring all your friends with guns.”

Sgt. Maj. Randall Carter, the top enlisted man in the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Marine Regiment, known in military shorthand as the 2/1, began to prepare his men.

“Marines are only really motivated two times,” he bellowed. “One is when we’re going on liberty. One is when we’re going to kill somebody. We’re not going on liberty . We’re here for one thing: to tame Fallouja. That’s what we’re going to do.”

The young Marines responded with a thunderous shout of “Ooh-rah!” the all-purpose Marine cheer.

Near midnight, the temperature was 41 degrees, one of the coldest April nights Al Anbar province had had in years. The Marines moved out, establishing their forward command post in the cemetery on the northern edge of town.

*

PREPARATIONS

Inside Fallouja, “we knew we would be wiped off the Earth,” recalled Kadhimia Abid Dulaimi, 59, a Fallouja woman who nevertheless helped insurgents, feeding them and letting them station themselves on her roof.The insurgents’ movements paralleled those of the Marines: They readied their weapons, scoped out buildings to use as sniper positions and stockpiled ammunition, said several Falloujans who fled a few days later.

A year after the U.S.-led invasion, the insurgency based in Fallouja had grown into an increasingly sophisticated movement made up largely of Iraqis — former Baath Party members, unemployed members of Hussein’s military and intelligence services, and Sunni fundamentalists who wanted Iraq to be governed by Islamic law, Marine intelligence officers said. Foreign fighters were in the minority but were believed to be responsible for many of the suicide bombings.

On April 5, the Marine operation was underway. Carter and the 2/1 advanced into the northern part of the city and almost immediately ran into resistance. Insurgents on rooftops and others in cars peppered the incoming troops with gunfire and rocket-propelled grenades.

“If they want to come out and fight, that’s fine with us,” Maj. Brandon McGowan, executive officer of the 2/1, said at the time. “That way we don’t have to go house to house.”

Five Marines died in that first day of combat. Insurgents died too, as did some civilians.

“There was a girl of 20 years who went out to our nearby mosque to give blood, and she was hit in the head by a piece of shrapnel,” said Umm Marwan, who fled with six of her children four days later. “The men carried her to the clinic, but I think she died before she got there.”

On April 6, the Marines pushed farther into the city and ran into stiffer resistance. The insurgents came up with a strategy to slow the American advance. They blocked streets with buses and trucks to try to force the Marines onto routes where insurgents lay in wait. They ferried fighters from place to place in cars and even in city buses. They used an antiaircraft gun to fire on U.S. helicopters that roared over the rooftops, until the Marines destroyed the weapon.

On April 7, the Arabic-language satellite TV channel Al Jazeera carried a report from the city’s hospital director, Tahr Issawi, that 60 people were dead. There was no way to verify the number or how many were civilians.

*

EYE ON NEWS

Watching the news unfold from his ranch near Crawford, Texas, on April 7, Bush twice requested video briefings directly from Abizaid and Bremer.The Marines were making progress and taking few casualties. But Arab media reports of civilian deaths sparked protests among Iraqis outside Fallouja. Al Jazeera had a correspondent inside the town, Ahmed Mansur, and his broadcasts were vivid and emotional. He interrupted one report from the roof of a building to hit the deck as a U.S. warplane passed overhead.

After U.S. artillery hit a mosque that the Americans said had been sheltering insurgents, Mansur reported that a family had been killed in a car parked behind the mosque. He also said 25 members of a family were killed when their house was hit.

In his wood-paneled office at the Republican Palace in Baghdad, Bremer was besieged by Sunni members of the Iraqi Governing Council who pleaded to be given safe passage to Fallouja to try to negotiate a peace, top aides said.

Sunni tribal leaders, clerics and physicians appealed to Hachim Hassani for help. Hassani was the No. 2 man in the Iraqi Islamic Party, the most powerful Sunni political organization in the country, and he often represented the party on the Governing Council. He was also an English-speaking economist who had lived nearly 15 years in Detroit and, more recently, Woodland Hills. Bremer saw him as trustworthy and moderate.

Hassani was getting regular updates on civilian casualties in Fallouja and complaining to U.S. officials.

“Hachim was telling us that of the people killed, maybe 20% were civilians,” said a senior Bremer aide who asked not to be named, adding that Hassani said that “even if it was 5%, that was 5% too many.”

U.N. envoy Brahimi had just landed in Baghdad to help assemble an interim government. He told Bremer, “I can’t operate this way,” complaining that the offensive made political negotiations impossible, a U.S. official in Baghdad at the time said.

A few days later, Brahimi publicly called the military’s response in Fallouja “collective punishments” and “not acceptable.”

Criticism also came from Britain’s Blair, the key U.S. ally in Iraq. The prime minister had been under pressure for more than a year from an antiwar majority in his ruling Labor Party, and the civilian casualties in Fallouja were causing the opposition to flare.

“The U.S. forces have to stop acting like warriors and start acting like peacekeepers,” said Blair’s former foreign secretary, Robin Cook. Blair telephoned Bush on April 7 to warn that the offensive in Fallouja was causing a backlash in the rest of Iraq, diplomats said.

The military felt the battle was also becoming a recruiting tool for the insurgency inside and outside Iraq. As portrayed on Al Jazeera, Fallouja was “a rallying call, an Alamo if you will, for the jihad,” Col. Coleman recalled.

U.S. military and civilian officials would later blame each other for allowing the Arab media to paint the offensive as an attack on civilians, mosques and hospitals. Under the strain, relationships between American civilian and military officials — including Bremer and Sanchez — were becoming “dysfunctional,” one official in Washington said.

Meanwhile, the Iraqis who were to fight alongside the U.S. troops drifted into the desert. The 2nd Battalion of the Iraqi army refused to take up arms against fellow countrymen. An Iraqi national guard unit walked as well. There was no way to put an Iraqi face on the battle.

The assault on the Sunni stronghold had the unexpected effect of buoying radical Shiite Muslims, especially those who followed the anti-American cleric Muqtada Sadr, who sent supplies to Fallouja during the Marine assault. Sadr used the events in Fallouja to help spark one of several uprisings against the occupation, in the Shiite holy city of Najaf.

The upsurge in fighting alarmed Americans as well. Even before the battle, a poll released April 5 found Bush’s overall job approval at a new low of 43%.

“We are on the verge of losing control of Iraq,” said Sen. Joseph R. Biden Jr. of Delaware, the ranking Democrat on the Foreign Relations Committee. Added Sen. Robert C. Byrd (D-W.Va.): “Surely I am not the only one who hears echoes of Vietnam.”

Rumsfeld sought to put out the fires.

“The number of people involved in those battles is relatively small . A small number of terrorists,” he told reporters at the Pentagon on April 7. “Some things are going well, and some things obviously are not going well. And you’re going to have good days and bad days, as we’ve said from the outset.”

The Marines pressed on. By April 9, Mattis believed he was within 48 hours of taking the city.

*

BAGHDAD TALKS

In Baghdad, a group known as the Iraqi Security Committee was meeting every day and sometimes twice a day. The committee consisted of a handful of Iraqi Governing Council members, the Iraqi national security advisor and the heads of the Iraqi Defense Ministry, Interior Ministry and the intelligence service. Bremer also attended.“The situation was very tense,” recalled Hassani, the Sunni leader. “The violence by then had spread around Fallouja. I thought the situation was getting very dangerous and we needed to interfere.”

On April 8, Hassani and Ghazi Ajil Yawer, another influential Sunni and member of the Governing Council, met with Adnan Pachachi, the usually pro-American elder statesman of the council’s Sunni members. The three emerged from Pachachi’s headquarters and said they were prepared to resign in protest, a move that could cripple the council and undermine Bush’s promise to turn over sovereignty to Iraqis on June 30.

A call came almost immediately from Bremer’s office asking for a meeting that night.

The Sunni politicians arrived to find the two top U.S. generals in the Middle East, Abizaid and Sanchez, in Bremer’s office. According to one participant, Abizaid told Hassani, “If you give me two days, I’ll finish Fallouja.”

Hassani, who appeared stunned, replied, “Yeah, you may finish Fallouja but I guarantee you, you’ll have all Iraq as one big Fallouja.”

Privately, American officials were divided over what course to take. One later said he thought the Sunnis were only “grandstanding.” But Bremer was convinced that continuing the military offensive would create a political disaster, and supported the idea of a cease-fire to allow the council members to try to negotiate a deal.

Abizaid and Sanchez were reluctant, participants said, but finally came around. “I know major military action could implode the political situation,” Abizaid said, according to one official.

Another person at the meeting recalled that the generals also said, “We can’t pull out our troops until we’ve got some kind of local force on the ground.”

The White House also acceded to the mounting pressure. The new view was: OK, give negotiations a try, officials said. But the time element was important. U.S. officials at the National Security Council didn’t want the negotiations to go on forever. Give them a deadline, a couple of weeks, they said.

In the early hours of April 9, the orders reached the Marines at Fallouja: A cease-fire begins at noon. By that point, the Marines would later estimate, they had taken a third of the city with relatively modest U.S. losses — 11 dead.

That afternoon, Bremer’s spokesman, Dan Senor, and Sanchez’s spokesman, Gen. Kimmitt, announced a “unilateral suspension of offensive operations.”

Senor said the purpose was “to hold a meeting between members of the Iraqi Governing Council, the Fallouja leadership and leaders of the anti-coalition forces, to allow delivery of additional supplies provided by the Iraqi government, and to allow residents of Fallouja to tend to the wounded and dead.”

Kimmitt warned that should discussions fail, “the coalition military are prepared to go back on the offensive.”

*

Part II

CEASE-FIRE

The Marines were unhappy. They had not wanted to attack Fallouja initially, but once their advice was ignored, their only goal was to crush the enemy. Now, they felt, they were being called off just when victory was within their grasp.Conway seethed in private. Months later he went public with his discontent, an unusual step for a Marine general.

“I would simply say that when you order elements of a Marine division to attack a city, that you really need to understand what the consequences are, and not, perhaps, vacillate in the middle of something like that,” he told reporters. “Once you commit, you’ve got to stay committed.”

By midmorning on April 9, the Marines began to relax their cordon around the city to allow women, children and the elderly to leave. Nearly a quarter of the city’s population of 285,000 fled through military checkpoints.

Col. John Toolan, commander of the 1st Marine Regiment and a veteran of the taking of Baghdad a year earlier, went to one of the checkpoints. Gun on his hip, he stopped cars in a search for insurgents. He found none, but came across Iraqi policemen and Civil Defense Corps troops fleeing the city.

“When are these people going to discover their manhood and stand and fight with us to save their city?” he demanded at the time.

Meanwhile, insurgents in the city regrouped. They still had considerable assets, including artillery and antiaircraft capability. They were controlling mosques and intimidating religious and civic leaders. They had popular support, and help from some Iraqi police, who were driving cars given by the U.S.

The guerrillas were not under the same restrictions as the Americans and continued to attack Marine positions and patrols. The Marines responded in force. The director of Fallouja Hospital appeared several times a day on Arab satellite TV channels with ever higher estimates of the death toll. On April 9, it was 450. A few days later it was 600.

From the Marines’ viewpoint, there seemed to be no reliable way to separate civilians from insurgents.

Elderly men were picking up AK-47s and fighting. Two Fallouja women later described preparing food for the insurgents and giving them shelter. “I cooked rice and lentils for them . I got them ammunition and held their guns for them as they were climbing onto my roof,” said Dulaimi, the homemaker.

During the periods of relative calm, those who did not flee emerged from their houses to bury the dead. They carried the bodies wrapped in white sheets to the soccer stadium, which had been turned into a graveyard because Marines were camped in the cemetery.

Meanwhile, various groups, all claiming to represent Falloujans, clamored to be the ones to negotiate a peace deal. The jockeying made talks difficult.

“There are lots of groups offering to negotiate,” said Senor, Bremer’s spokesman. “We will talk to anybody, but at the moment we are not sure that anyone is actually able to negotiate on behalf of the people of Fallouja.”

In Washington, the picture wasn’t much clearer. “Most of this was opaque to us in Washington, certainly the details,” one official said later.

With negotiations yielding little, Mattis called in reinforcements. He had begun the fight with only two battalions; by late April, he had seven.

At the same time, the Marines began to assert control over negotiations, trying to employ the tactic they had wanted to use in the first place: turning to moderate Falloujans to help manage the city.

Marine commanders were inclined to believe that former members of Hussein’s armed forces were adherents of military order and could offer the city effective leadership. The Marines also had some empathy for the fighters who were former military men — a type they knew well. The ex-fighters had been ignored by officials in Baghdad since the war, much as the Marines felt that their advice often fell on deaf ears.

The Marines recognized that many of the fighters “weren’t former regime loyalists, they certainly weren’t foreign fighters, and they weren’t religious extremists,” said Coleman, the colonel.

“They were soldiers who have families,” Coleman said later. He noted their frustration over being unemployed for a year after the army was disbanded. “They couldn’t do the things a man and a father is expected to do and then a force is all of a sudden arrayed and directed against your town. What do you do? Many of those men chose to pick up that AK-47 and join the fight.”

The Marines turned to the head of the Iraqi intelligence service, Gen. Mohammed Shahwani, a onetime Hussein operative and a strong supporter of turning to former Hussein-era military men, several of the parties involved said.

Shahwani had fled Iraq in the early 1990s and was a key player in an abortive coup in 1996, backed by the CIA, according to secret police files kept by Hussein and obtained after the war by Ahmad Chalabi, a formerly exiled political leader.

“Gen. Shahwani and I were in direct contact,” Conway said later. “He felt like he knew who some of the quality soldiers were from this region, and he did bring these people forward.”

Conway explained that he wanted a “charismatic Iraqi general.” Shahwani brought him Gen. Mohammed Latif and Maj. Gen. Jassim Saleh. Latif was a former head of military intelligence and Saleh had been a general in the armed forces. At a meeting at Camp Fallouja, Shahwani presented the two men along with two others as the right people to lead an armed force in Fallouja.

Coleman was impressed by Latif, whom he described as a natural leader, but Saleh was necessary for the deal to work. “Saleh was a son of the city, so he could walk right in there and command immediate respect,” Coleman said. He was also a professional military man.

Saleh walked into the Fallouja post wearing the traditional Arab robe known as a dishdasha. “We called our troops to attention and gave him the kind of Marine military salute we would to someone of that rank,” recalled Maj. Ed Sullivan.

Some Marine officers, including Sullivan, found Saleh almost a caricature of a Hussein-era general. “He played the part wonderfully. He was excessively polite. He met with Col. Toolan. He said, ‘Your men fight like tigers,’ ” Sullivan recalled, shaking his head as he remembered Saleh’s confidence.

It didn’t take long for the Marines to recognize that Saleh, son of the city or no, might also be a problem. He turned out to be one of the leaders of the insurgency near Taji, a town just north of Baghdad, one Marine officer said. Saleh had been one of the insurgents planning the attacks on a large U.S. military base known as Camp Anaconda, military officials said.

At the same time, in an attempt to reach out to the larger Sunni community, Bremer announced a softening of the coalition policy that had stripped many Sunnis of their Hussein-era government jobs. But no decision in Iraq seemed to come easy; Bremer’s move angered Shiite leaders, who accused him of reneging on his commitment to dismantle Hussein’s Baath Party power structure.

When the idea of turning over security to a force headed by Latif and Saleh was brought up to Iraq’s interim ministers, they expressed dismay.

“It was the equivalent of the poachers becoming the gamekeepers,” said Ali Allawi, then interim minister of defense.

On April 29, Mattis held a long negotiating session with Latif, Saleh and two other former Iraqi generals. He struck a deal to allow them to raise a force of local men — the Fallouja Brigade — to take control of the city.

Mattis apparently intended to report the agreement up his chain of command before any public announcement was made, but a Los Angeles Times reporter was outside the meeting between Mattis and the Iraqi generals, and Mattis reluctantly confirmed what was already apparent.

The deal took other U.S. officials by surprise — Bremer and Sanchez in Baghdad, and Rumsfeld and Bush in Washington.

A U.S. official in Baghdad said Abizaid telephoned Bremer and asked, “What’s going on down there?”

“I have no idea,” Bremer replied.

“It was a complete surprise to us,” the official said. “Both Bremer and Abizaid were shocked. Bremer was furious . Bremer learned about it from the press. The Marines sort of said, ‘Presto, here it is.’ ”

In Washington, once it was clear that a deal had been struck, Rumsfeld announced a fait accompli. “The Marines on the ground are the ones that are making those judgments,” he told a television interviewer.

At the White House, the move also was presented as a done deal, officials said. “We were told there was a deal,” one official said. “We all kind of shook our heads and said, ‘OK.’ ” Next to Bremer’s warnings that renewed fighting would torpedo the formation of a new Iraqi interim government, the deal looked “acceptable,” he said.

But Bremer and his aides complained privately about what they saw as the military’s tendency to sideline the civilian authority. “You need a clear definition of what’s a military decision and what’s a political decision,” one civilian official in Washington said. “In this case, the Marines stepped across that line.”

Pentagon spokesman Di Rita defended the Marines against that charge. “They had an enormous amount of authority to go work the problem,” he said. Mattis, who made the deal, was promoted to lieutenant general in September.

Iraqi national security advisor Mowaffak Rubaie, who is also a Shiite and deeply distrustful of the minority Sunnis who were part of the Hussein regime, learned of the Fallouja Brigade on May 1 when he read an account in a Western newspaper. The same day, he attended an early-morning meeting in Bremer’s office.

“We went full blast. We said: ‘This is wrong, you are repeating the same mistake you made in Afghanistan with the warlords . This is going to backfire.’ It was appeasement,” Rubaie said.

Allawi, the interim defense minister, feared that U.S. officials would be tempted to clone it elsewhere — in Najaf, Mosul and Basra — leading to multiple militias and a security disaster, and that the strategy would eventually fail.

“I said, ‘You’ll get a period of relative quiet and the city will breathe a sigh of relief, but it will only be camouflage and subterfuge,’ ” recalled Allawi, who now lives in London.

But there was no turning back.

*

Part III

NEW BRIGADE

With 16 men lost to hostile fire since the offensive began April 5, the first three days of May grated on many of the Marines who had fought to take the city. Hour by hour they ceded positions to newly minted members of the Fallouja Brigade, whom they had been fighting only days before.“We gave them a battalion’s worth of rifles, about 800 rifles, I think,” Gen. Conway said later. “Probably 25 to 27 trucks, probably 40 or 50 radios, and about 2,000 uniforms.”

Lance Cpl. Jacob Atkinson, 21, of Richmond, Va., said at the time, “I just hope whoever is making the decision for this has a good plan.”

His 150-member unit, Echo Company of the 2/1, had suffered significant casualties — three Marines dead and more than 50 wounded — during a month of combat and negotiations.

Echo Company’s commander, Capt. Douglas Zembiec, tried to cool his men down. “I told every one of them, ‘Your brothers did not die in vain,’ ” said Zembiec, 31, of Albuquerque. “ ‘We’ll give this a chance. If it doesn’t work, we’re prepared to go back in.’ ”

Among Falloujans, the mood was one of heady excitement, pride and relief. One of their own was back in charge. Jassim Saleh was welcomed with cheers and applause as he strutted through downtown wearing his Hussein-era uniform.

There was joy, too, that the Americans, all the more hated after a month of bombing, were leaving. But there was also dismay as many Falloujan natives, who had left during the worst of the fighting, returned to find their homes, businesses and mosques reduced to rubble.

Hot weather had arrived, and flies swirled in clouds. At the edge of the Jolan neighborhood, an insurgent stronghold, Fallouja Brigade recruiters took applications from what seemed like an endless line of men.

Yassir Abaat, 28, who said he used to work for Hussein’s presidential guard, joined the insurgency after his father was killed on the fourth day of the Fallouja siege.

“I have not stopped fighting. The war is not over,” he said in a calm voice. “If the Americans attack again, we will defend ourselves.”

Conway listed several missions that he expected Saleh’s brigade to accomplish. They would kill or capture the foreign fighters battling U.S. forces, they would find and arrest the killers of the U.S. contractors, they would make the city safe for Westerners to enter and begin reconstruction, and they would ensure that the insurgents’ heavy weapons were handed over.

Saleh would not be around long enough to make any of that happen, however. The Marines removed him amid Shiite accusations that he had been a commander for Hussein when atrocities were committed in southern Iraq. By early May he was out, replaced by Latif, whom the Marines had preferred from the start but who lacked Falloujan roots.

Under Latif, the experiment seemed to work at first. The city was peaceful. Civilians no longer were dying, and the destruction of homes and shops had stopped. Not a shot was fired at the Marines there, and most of the province was quiet as well.

Under the agreement, the Marines did not venture into Fallouja without an escort. But they worked relatively freely in surrounding villages and towns and were able to pay salaries, give compensation to those who had lost children or other civilian relatives in the fighting, and rebuild mosques and hand out bags of seed to farmers.

Coleman considered Latif a military professional and credited him with much of what was going right.

“You can look the man in the eye and you feel a power and presence there that, at least in our profession, you associate with a natural leader,” he said.

On May 10, the Marines made their first and only patrol in the city center with the brigade. When it was over, Iraqi national guard and Fallouja Brigade members waved their guns in the air chanting, “From Fallouja to Kufa,” a suggestion that the Iraqis should free their cities from American domination from central to southern Iraq.

From that point on, the brigade wanted the Marines to stay out of Fallouja, period. An Iraqi police captain said as much to Mattis.

In Washington, Bush and his aides insisted that progress was being made. “In and around Fallouja, U.S. Marines are maintaining pressure on Saddam loyalists and foreign fighters and other militants,” the president said at a Pentagon ceremony May 10. “We’re keeping that pressure on to ensure that Fallouja ceases to be an enemy sanctuary.”

But as the month wore on, U.S. forces were no closer to vanquishing the insurgency or ridding the area of foreign fighters, and no closer to finding the killers of the contractors. Fallouja had become a no-go zone for the Marines.

*

Part IV

MORE ATTACKS

In June, insurgents began to push outside the city limits. They staked out the nearby Marine bases and targeted people entering and leaving.On June 5, six Shiite truck drivers, outsiders in Sunni-dominated Fallouja, became frightened at an insurgent checkpoint and rushed to the police station for help. The police took them to a mosque, where they were handed over to insurgents. They were executed and their bodies mutilated, according to Shiite tribal sheiks and news reports.

Most Westerners steered clear of the highway near Fallouja. If they had to travel to western Iraq, they waited for a military flight.

By mid-June, the U.S. military believed that many of the bombings of civilian targets and other terrorist acts throughout Iraq were being directed by Zarqawi from Fallouja.

On June 19, the U.S. launched airstrikes there on what were believed to be safe houses used by Zarqawi. At least two homes were destroyed and 18 to 24 people killed. It was the beginning of an effort to use precision bombing to go after Zarqawi’s network and other insurgents.

But the scenes Iraqis saw on Arab television told a different story. Emergency room doctors again said that many of the dead were women and children. Mothers cried over their lost sons — it was impossible to tell whether they were insurgents or civilians. People picked their way through ruined homes, looking in disbelief at the wreckage. Fallouja was off-limits to Western reporters.

The call to jihad found an audience in Fallouja, where an increasingly militant climate pervaded the city.

Young Iraqi men gathered at outdoor stands where hawkers sold videos shot by insurgents that showed suicide bombings in Iraq. The tapes featured testimonials from bombers before their deaths and then the explosive completion of their missions. Beheading tapes were also for sale.

Dulaimi, the Fallouja woman who had helped the insurgents in April, said that “most of the mujahedin are very brave people, and as long as they are doing something right, God will bring victory.”

*

VIPERS’ NEST

On June 28, Bremer transferred sovereignty to the new interim Iraqi government and then flew home. Fallouja was completely in the grip of insurgent forces, and the insurgency was spreading.“It is a nest of vipers, and the vipers leave Fallouja to go to Baghdad,” one U.S. officer said. He called the city and its untamed surroundings “the Cambodia of this war.”

Rubaie, the national security advisor, estimated that about 350 foreign fighters had gone north to the city of Samarra from Fallouja and that about 150 had gone west to Ramadi.

Leaders of the Fallouja Brigade cheerfully confirmed much of the account. “Now there is [Islamic] law in Fallouja,” said Mohammed Abid Makhlaf, a former brigadier in Hussein’s army who had become a leader of the Fallouja Brigade.

“There is a kind of social collaboration between the Iraqi police, the Iraqi national guard, the mujahedin and the Fallouja Brigade,” he said. “If there are robbers, the police and the mujahedin, with the imams of a mosque, will determine the punishment from a religious standpoint. For instance, if he is a robber, they will cut off his hand.”

He said the view of most Falloujans was: “The U.S. is our first enemy. All the people in Fallouja hate Americans because they hit them, they killed them, they destroyed the whole city. Now the situation is better because there are no Americans. Their touch is not there.”

*

NAJAF UNREST

In August, signs emerged that insurgents from Fallouja were aiding the Shiite insurgency 100 miles away in Najaf, where rebel cleric Sadr and his Al Mahdi militia had occupied the revered Imam Ali Mosque.Col. Durrant, who runs the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force’s coordination with the Iraqi security forces, recalled watching a television clip in which Falloujans were headed to Najaf “driving police cars we gave them, filled with arms and ammo we gave them.”

At the same time, attacks on foreigners, including beheadings, became almost commonplace. By the end of August, more than 100 people had been kidnapped — most of them by groups thought to be based in the Fallouja area, intelligence officers said. At least 20 were killed.

The insurgents also were trying to eliminate anyone in Fallouja or Ramadi — the two cities account for 70% of Al Anbar province’s population — who represented the interim government. The targets included members of the police, the national guard, ministerial appointees in the provincial offices, governors and their deputies.

One such target was Col. Suleiman Marawi, the head of one of two Iraqi national guard battalions based in Fallouja and a key ally of the Americans.

Marawi was attacked as he returned to the guardsmen’s base outside the city. He managed to get into the base, but when a local imam offered to accompany him back into the city and mediate between him and his mujahedin attackers, Marawi agreed. He was soon turned over to the rebels, tortured and killed, Durrant said.

“They dumped his body by the side of the road,” Durrant said, adding that it “had marks from boiling water. It was not a fast death.”

Without Marawi, the national guard troops deserted. “The insurgents came in and took everything — beds, AK-47s, thousands of rounds of ammunition, machine guns, RPGs,” Durrant said.

In the last days of August, the U.S. stepped up its precision bombing in neighborhoods known to have been taken over by insurgents.

“There are no families there now. Around evening we hear bombing and we see smoke and fire. To stay there is to risk your life,” one woman said.

The Marines informed the Iraqi Defense Ministry that it would no longer pay the Fallouja Brigade’s salary. The ministry and the Marines dissolved the force.

In Washington, Rumsfeld told reporters, “The Fallouja Brigade didn’t work.”

On Sept. 9, Gen. Abdullah Hamid Wael, the brigade’s operational leader, announced the decision to the 2,000 members.

Supplied with U.S. weapons, ammunition, radios and vehicles, they turned their energies wholeheartedly to the insurgency.

Zarqawi and the killers of the American contractors, if they were in Fallouja, remained beyond U.S. reach.

Afterword

All through September and October, American warplanes bombed Fallouja in hope of killing Zarqawi and his followers, and in hope of forcing Fallouja’s remaining residents to plead for peace.

It didn’t work. Zarqawi remained at large, and the terrorist operations attributed to him continued. Fallouja’s ruling council negotiated with the Baghdad government, agreeing to expel foreign fighters and welcome the Iraqi national guard, but the deal fell through.

Nearly two weeks ago, interim Prime Minister Iyad Allawi ordered Falloujans to hand over Zarqawi or face a new assault. The leader of Iraq’s hard-line Sunni clergy, Sheik Harith Dhari, retorted that an attack would prompt a Sunni boycott of elections scheduled for January — a virtual death blow to the U.S.-authored timetable for Iraq’s political progress.

“The Iraqi people view Fallouja as the symbol of their steadfastness, resistance and pride,” Dhari said.

So the prime minister now faces the same dilemma Bush and Bremer faced in April: He can attempt to solve the problem of Fallouja with military force, but only at the risk of alienating Sunnis whose support the new government needs. If he leaves the insurgent stronghold to fester, the guerrillas will continue to gather strength.

Just as before, there is no easy choice, no clear course that will guarantee success. In April, the Americans found their options limited by earlier missteps: the decision to disband Iraq’s armed forces, the failure to reach out to Sunnis, the lack of political and diplomatic groundwork for military actions. The question is whether those factors will again stand in the way of success, or whether Iraq has changed enough that the new interim government can root out the insurgents.

This time, an Iraqi, not an American, would be at least nominally in charge of an attack. The troops who would storm the city would include Iraqis with more training and experience than in April. The people of Fallouja appear divided over whether to fight to the death or cut a deal.

But the ranks of hardened insurgents and foreign fighters in Fallouja have increased. The decisions the United States made in the spring — in particular, the creation of the Fallouja Brigade and the Marines’ promise to stay outside the city — gave the insurgents almost six months to dig in. That means Prime Minister Allawi has an even tougher battle ahead.

The Sunni insurgency whose seedbed was Fallouja has now spread far beyond the city’s borders. An Iraq with its Sunnis in perpetual rebellion will not be stable. Allawi and his American supporters face the difficult task of winning back not only Fallouja, but also the rest of Iraq’s Sunni belt — not only the control of its cities, but its hearts and minds as well.

Rubin reported from Fallouja and Baghdad and McManus from Washington. Times staff writers Mark Mazzetti in Washington, Patrick J. McDonnell in Fallouja and Baghdad, and Tony Perry in Fallouja and San Diego contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.