‘A new kind of pope’ is making a pilgrimage to Mexico

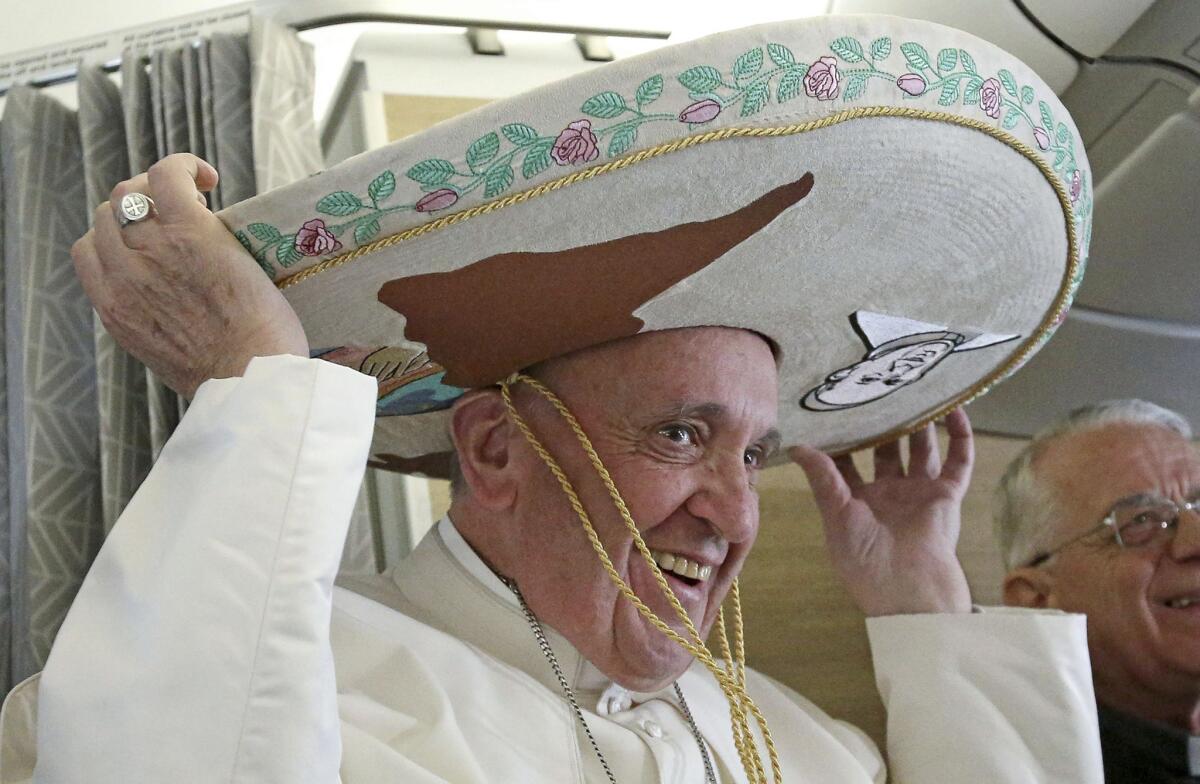

Pope Francis wears a traditional Mexican sombrero he received as a gift from a journalist aboard the plane during the flight from Rome to Havana, Cuba.

- Share via

As the archbishop of Buenos Aires, the future Pope Francis was a thorn in the side of the Argentine leadership, especially the husband and wife presidency of Nestor and Christina Kirchner.

“A major part of their platform was that they were in favor of the poor,” said Father Arthur F. Liebscher, chairman of the history department at Santa Clara University, “and he came along and said, ‘Well, what are you doing about it? You’re getting rich, your friends are getting rich, and nothing is happening in the country.’”

Liebscher remembers the pope when he was still Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio, a fellow Jesuit priest; the two men washed dishes together at a school in Argentina. Now, as Francis launches an ambitious trip to Mexico, Liebscher expects that the first Latin American pontiff will give the Mexican government of President Enrique Peña Nieto a taste of what the Kirchners once experienced.

Wending his way through the country, from the southern frontier with Guatemala to the northern border with the United States, Francis can be expected to make a far different imprint than his European predecessors, Popes Benedict XVI and John Paul II, both of whom also visited Mexico.

Part of that is cultural: Francis is Latin American to his core, a native Spanish speaker who has grappled with entrenched poverty and authoritarian governments for much of his life. Part of it may also be generational: The 79-year-old Francis was still a young priest when the Roman Catholic Church was profoundly changed by the Second Vatican Council, and he has shown far more allegiance to those reforms than did John Paul or Benedict.

Pope John Paul II is greeted by the crowds as he makes his way to the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City on Jan. 23, 1999.

Francis is no radical. His theology is doctrinaire Catholicism, and he has disappointed those who hoped he might revisit Catholic positions on birth control, abortion and the role of women in the church. Advocates for the victims of sexual abuse by priests say he has not done enough to end that scourge and punish bishops who turned a blind eye to it.

But reformers give him credit for taking on the Vatican bureaucracy, demanding that clerics live more simply, and offering a more positive vision of Christianity — one focused more on redemption than on sin.

John Paul visited Mexico on his first international trip as pope in 1979 and returned four times over the next 20 years. His visits were largely pastoral, drawing some of the largest crowds in human history. But they also were cautionary. Time and again, John Paul warned against the dangers of liberation theology, which called for the church to play a more activist role in bringing justice to the poor.

Benedict visited Mexico once, in 2012, inveighing against drug war violence and saying that faith in God was the way to overcome “all evil and to establish a more just and fraternal society.” The German-born pontiff, who had been the church’s doctrinal overseer under John Paul and had a reputation as a theological conservative, cerebral and reserved, resigned the next year, paving the way for Francis.

Pope Francis is a new kind of pope. Or, let me put it another way: He’s a return to an earlier way of being pope.

— Sally Vance-Trembath, a lecturer in religious studies at Santa Clara University

Francis’ trip promises to be a more intimate dive into Mexican society, a visit from a neighbor, albeit one who speaks an oddly accented Spanish and comes from a country, Argentina, that Mexicans view as aloof, even arrogant, and suspiciously European.

Francis has never been seen as a liberation theologist, but he is clearly more open to its ideas than were John Paul or Benedict. As a Latin American, he has more “communitarian” values than his predecessors and is single-mindedly devoted to the poor, said Timothy Matovina, a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame and co-director of the school’s Institute for Latino Studies.

John Paul, the first pope from Poland, was adamantly opposed to communism in Eastern Europe and is widely credited with helping to foment its fall. “Francis is not going to disagree with the form of government in Mexico,” Matovina said, “but he’s going to talk about how, if government isn’t serving the needs of the people, what good is it?”

He also can be expected to excoriate the practice of Mexican churches accepting narco-limosnas — donations, often quite generous, from drug traffickers.

Pope Benedict XVI waves to well wishers from the Popemobile in Leon, Mexico, on March 23, 2012.

More than anything, said Sally Vance-Trembath, a lecturer in religious studies at Santa Clara University, Francis can be expected to take time to listen to Mexican Catholics and learn from them. That, she said, may be the greatest difference between him and his recent predecessors.

“Pope Francis is a new kind of pope,” she said. “Or, let me put it another way: He’s a return to an earlier way of being pope from the ancient church. He’s not a monarch, he’s not the CEO, he’s not the head of the church in the way that Benedict and John Paul II were. He’s the bishop of Rome, first and foremost.”

As such, she said, he sees himself as one bishop among many, presiding over a church that has universal values but diverse ways of expressing them.

The pope’s itinerary may be a reflection of his intent. Although he will base himself in Mexico City, he will radiate out each day to places that are associated with marginalized people – indigenous groups, victims of violence and, perhaps most pronounced, migrants who cross Mexico along a path from Guatemala to the heavily fortified U.S. border that divides Ciudad Juarez from El Paso, Texas.

“He’s doing the path, he’s going into the problem areas, and he’s said, ‘I’m coming to pray with you, I’m coming to learn more about the Mexican way of being Catholic,’” Vance-Trembath said.

Follow @latlands on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.