Fidel Castro’s final tour across the homeland he ruled for nearly half a century

- Share via

Reporting from MATANZAS, Cuba — A white helicopter circling above the central Plaza of Liberty signaled that the long-awaited moment was imminent.

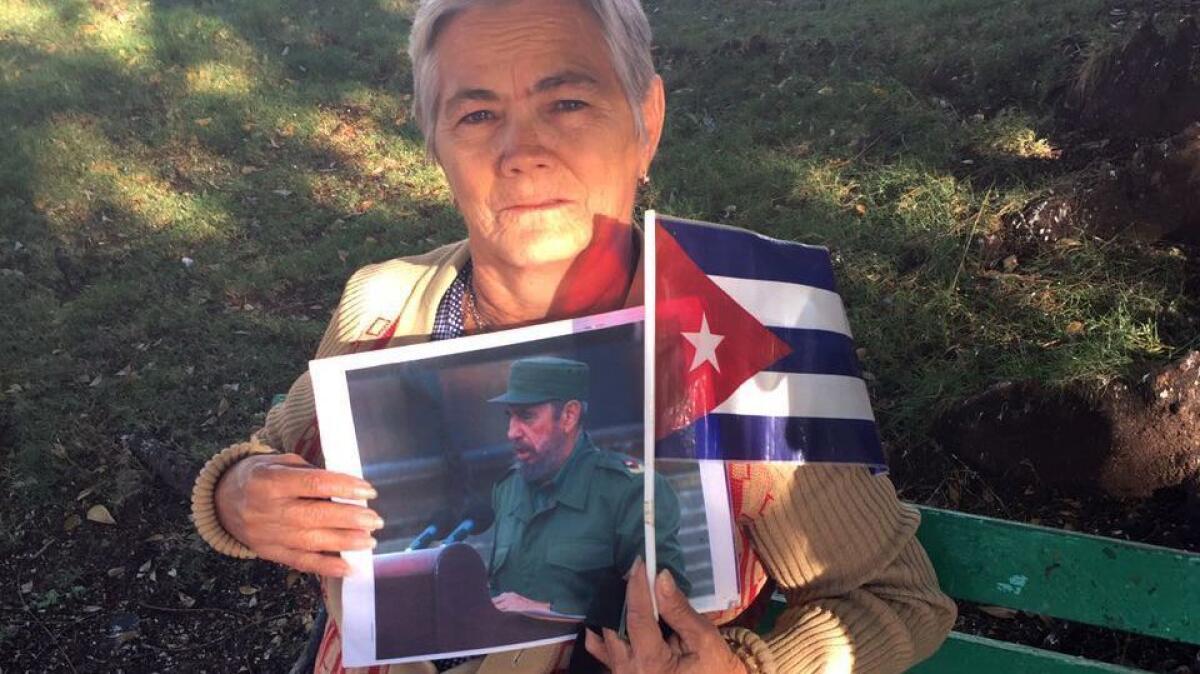

Onlookers who had been waiting for hours were lined three and four deep along the narrow streets, straining for a glimpse at this historic cortege. They hoisted children on their shoulders. Everyone seemed to have a Cuban flag or a portrait of the bearded man.

Revolutionary banners hung from the colonial-era buildings flanking the plaza in this agricultural outpost about 50 miles east of the capital, Havana.

Finally, several police motorcycles leading a convoy of vehicles rumbled down the main drag, which had been cleared of traffic.

Photographers and camera operators riding in a flatbed truck focused their lenses on the crowd. A military jeep pulled a trailer bearing the precious cargo, encased in glass, flanked by white flowers: the ashes of Fidel Castro.

“Yo soy Fidel!” came the cry from the assembled multitudes. “I am Fidel.”

The Cuban leader was cremated Saturday, a day after his death at age 90. Dubbed the “Caravan of Liberty” by Cuban authorities, this was his final swing through a homeland that he presided over for the better part of half a century. The Cuban state went out of its way to make it a big deal.

Keen to preserve Castro’s message, officials came up with a novel plan: Ferry the ashes in a public procession from Havana to the southeastern city of Santiago, nearly 475 miles away, where the remains are to be interred Sunday, the final step in a series of mega-events that marked a nine-day official mourning period.

State television and radio have talked up the caravan for days. In Havana, people began lining the streets just after sunrise to witness the 7 a.m. start.

Matanzas, a port city of 150,000 people, was the first major population center on the caravan’s trek from Havana. People seemed excited about the event, though in Cuba it can be hard to discern genuine enthusiasm from a sense of duty. Some of the onlookers were in tears.

Once a sugar cane hub, Matanzas doesn’t feel especially prosperous these days. At least one abandoned sugar cane refinery was visible along the coastal road snaking from the capital, its smokestacks forlorn in the distance. A plaque in the central square recalls a 19th century rendition developed here of the danzon, the lively Cuban national dance and musical genre. But music and booze have been banned for the mourning of Castro.

Posters hailed Castro’s July 26th movement, as his guerrilla group was known as it attacked military posts in Cuba during the revolutionary period. Matanzas still boasts veterans of the campaign, and loyal residents like to call the town “the crib of the revolution.”

Elderly Cubans seemed most anxious to praise Castro, who is officially revered here as a champion of the poor — even while reviled among Cuban exiles in Miami as a brutal dictator who dispatched Cuba into a dark era from which it has yet to emerge.

“If it wasn’t for El Comandante Castro my life would never have changed,” said Maria Elena Navarro, 65, who was among the hundreds lining the streets here, hoping for a glimpse of the urn holding the ashes. “Our comandante fought for our rights and we have a lot to thank him for.”

“I recognize that some things are bad, but that’s the fault of the infamous blockade,” she said, echoing the official line blaming Cuba’s woes on the more-than-half-century-long U.S. trade embargo against Cuba. “The young people shouldn’t forget that we have to continue. The revolution cannot be allowed to die. Many died so that we can all enjoy a better life.”

Indeed, much of the official extolling of Castro as a revolutionary “example” seems intended to persuade Cuba’s sometimes skeptical younger generation of how good they have it. Young people tend to ask awkward questions about the lack of jobs, opportunities and Internet on the island. Castro’s barbudos, or bearded ones, as the revolutionary cadres were known, are mostly grainy black-and-white images on TV.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen now,” said Bernardo Gonzalez, 27, expressing a general uncertainty in a world without Fidel Castro.

His absence creates a void both for supporters and detractors.

“Changes have been very slow,” Gonzalez said. “I don’t have much hope there will be rapid changes. It will take a long time.”

Reminding Cubans of the revolution is a key aim of the state apparatus in these days. The entire mourning exercise is freighted with symbolism.

In 1959, after seizing power from Fulgencio Batista, the U.S.-backed dictator, Castro and his bearded colleagues traveled from Santiago to Havana. For many Cubans, it was the first time they had seen their new leader and his bedraggled guerrilla army.

In black-and-white clips now ubiquitous on state television, the rebels of yesteryear project an image of youthful idealism and energy. It’s a far cry from the current Cuban state, which critics call sclerotic and outdated, despite its achievements in providing free education and healthcare to the masses.

For this week’s caravan, the route of 1959 was reversed. The tour seemed to have the desired effect of whipping up support for Castro’s legacy and the current government, headed by Raul Castro, Fidel’s brother, who is 85 and has vowed to retire in two years.

In the plaza here in Matanzas, schoolchildren scrawled graffiti in white chalk. The messages were all demonstrably politically correct.

“Fidel, you are in the heart of all Cuban youth!” read one, with a stylized heart in the middle.

Another message read: “Eternal Fidel!”

No public protests have been seen during the mourning period. A heavy police presence accompanied all events, including the caravan.

The convoy whizzed by Matanzas at relatively high speed. Many never saw the urn carrying Castro’s remains. But that didn’t seem to dim the enthusiasm.

“We are all Fidel!” came the chant as the crowd began to disperse, some hangers-on waiting to see whether there was more to come.

But the caravan continued its journey east along the coast, carrying the remains of the man who has inspired intense affection and bitter loathing, and whose passing seems to leave behind more questions than answers for the Cuban people.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sanchez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.