In El Salvador, they quietly guarded Oscar Romero’s legacy. At last, they can celebrate his sainthood

- Share via

Reporting from Rome — After he was killed, they burned his photographs and nearly every memento they had of their friend. The rest they buried in their garden, just beneath their guava tree.

Maria Hilda and Guillermo Gonzalez feared saying his name, even to their closest relatives.

It was 1980, and a brutal war grabbed hold of El Salvador soon after Archbishop Oscar Romero was shot in the heart as he celebrated Mass in a hospital chapel.

To them and thousands of other Salvadorans who fled the violence in their homeland and came to Los Angeles, Romero was a hero who fought against oppression, against the massacre of the poor.

To others, he was an agitator. They called him a leftist, guerrilla, communist.

Long after he died, Romero’s legacy remained so polarizing that the Roman Catholic Church took decades to decide whether he deserved to be a saint.

The moment we’ve waited for so long is finally here.

— Maria Hilda Gonzalez

Now 68 and 71 years old, Maria Hilda and Guillermo of Granada Hills thought they would never live to see this day — traveling to Rome for Romero’s canonization.

‘Enough already!’

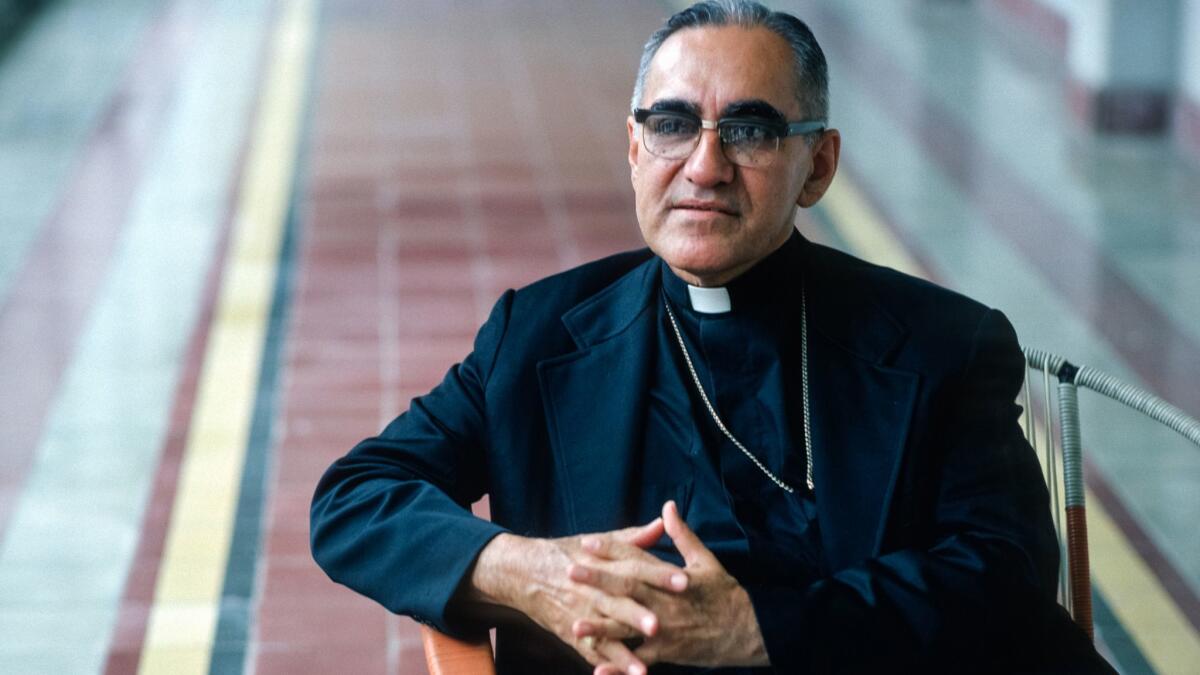

They were college students when they met him. He visited the small town of Aguilares with his signature half-rim glasses and his solid black cassock.

Monseñor Romero, as he was widely known, was the new archbishop of San Salvador, expected to be meek and conservative. But in the late 1970s, the systematic killing of the poor brought on by right-wing death squads pushed him to speak up.

“Basta ya!” (Enough already!) Guillermo remembers him shouting at the funeral of Father Rutilio Grande, a friend of Romero’s who was shot more than 14 times.

Every Monday night in the capital, Guillermo and Maria Hilda would attend Romero’s prayer study group.

The couple came from well-off families. Guillermo’s parents had a vast amount of land, and Maria Hilda’s family owned a grocerystore and a transportation business.

Romero taught them to look beyond themselves.

We’re all important, he would say. You have to have a conscience. You have to be the microphone of God.

On a recent evening, the Gonzalez family gathered for dinner at their home in Granada Hills. Three generations sat together to talk about baby Liam’s first haircut, Maria Hilda’s homegrown papayas and a long-awaited trip to Rome that was only a week away.

Images of Romero were everywhere: on the dining table, on the coffee table and on top of an altar near the television. There, too, in a custom crystal case marked with Romero’s coat of arms, stood his old microphone.

Maria Hilda stashed it in her suitcase when she came to the United States in 2002.

Their time in Los Angeles has been devoted to speaking about this man who became their life so many years ago. They take Romero’s photo, his microphone and his story to churches, prayer groups and homes all over: South L.A., San Bernardino, Salinas, San Diego.

At one presentation in North Hollywood, a former military sergeant from El Salvador stood up and apologized for killing people.

“Many have felt a deep connection during our talks and open their hearts to us,” Maria Hilda said.

But the path has not been easy. At some churches, especially at the beginning, some would walk out of their presentations. Right-wing Salvadorans in the audience labeled them guerrillas. At some churches, officials refused to play their video about Romero’s life. At others, they would be invited to speak, then at the last minute, turned away.

Father Roberto Mena, a priest now working in Mississippi, used to help Maria Hilda and Guillermo years ago when he was based out of a parish in Compton. The couple would tell him all about their struggle.

“Keep going,” he would say to them. “You’re lucky there’s so many churches in California.”

What Maria Hilda and Guillermo longed for most was news from the Vatican. Romero’s path to sainthood, initiated in 1990, had been stalled for years by church conservatives’ efforts.

When news came this year that Pope Francis had approved the canonization, the two were ecstatic. They fell to their knees in their living room and cried.

‘Full of joy’

Three days before the big ceremony, Rome was cool and drizzly, buzzing with anticipation. Tens of thousands were expected to descend on St. Peter’s Square on Sunday.

Salvadorans, many from Los Angeles, were everywhere, decked in the blue and white colors of their flag. They wore hats and pins and shirts with images of Romero smiling.

Maria Hilda and Guillermo walked into the crowd to interview a few pilgrims. Many of them know her from a Catholic news channel.

“Maria Hilda, como esta?” said one woman,Carmencita, embracing her in a hug.

“Full of joy,” Maria Hilda responded. “The moment we’ve waited for so long is finally here.”

As Maria Hilda interviewed pilgrim after pilgrim on the square, Guillermo recorded her with his cellphone. She carried a microphone, one issued to her by the news channel.

Back at her hotel, safely wrapped in two scarfs inside her suitcase, was the other microphone.

It had to be by their side on this special day.

Para leer este artículo en español haga clic aquí.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.