The people of Mosul, Iraq, find there’s life after Islamic State, but it isn’t easy

For many, a year and a half later, authorities are doing little to help those who had suffered under the extremists’ rule to rebuild their shattered lives.

- Share via

Reporting from Mosul, Iraq — In the biblical book of Jonah, God wants to destroy the city of Nineveh because of its wickedness, but Jonah begs him to have mercy, and he relents.

Today, what was once Nineveh is the eastern half of the Iraqi city of Mosul, where a version of the biblical story has played out again. In the siege that drove Islamic State militants from Mosul, the east side was largely spared.

For the record:

3:10 p.m. March 12, 2019This article misstates the biblical story of Jonah, who did not beg God to have mercy, but rather delivered a warning that the inhabitants of Nineveh heeded, causing God to spare them.

The west side is an entirely different story.

If it were possible to stand at the center of the Tigris River where it bisects this ancient city, once the crown jewel of Islamic State’s conquests, the view might bring to mind an oft-repeated cliche: Mosul has become a tale of two cities.

Looking east, you’d see crowded restaurants and “casinos,” the riverside cafes where men suck on water pipes as they play cards with gusto.

The smoke of a dozen barbecue joints would waft over the area, and at night, cars would jostle for space on a brightly lighted thoroughfare.

Look west at night, and you’d see very little. The west lacks electricity, and even if there were power, there are no street lamps left standing.

Sunlight unmasks this “right bank” of Mosul as a topography of rubble, the crushed remains of the thousands of buildings that once stood here. It’s a cityscape scrubbed out with a gray-brown brush, where residents casually walk past a skull peering from a head-high mound of rocks, rebar and trash.

It was in 2017 that more than 100,000 Iraqi troops and militiamen, backed by a U.S.-led coalition, routed the Islamic State fighters who had made Mosul their Iraqi capital.

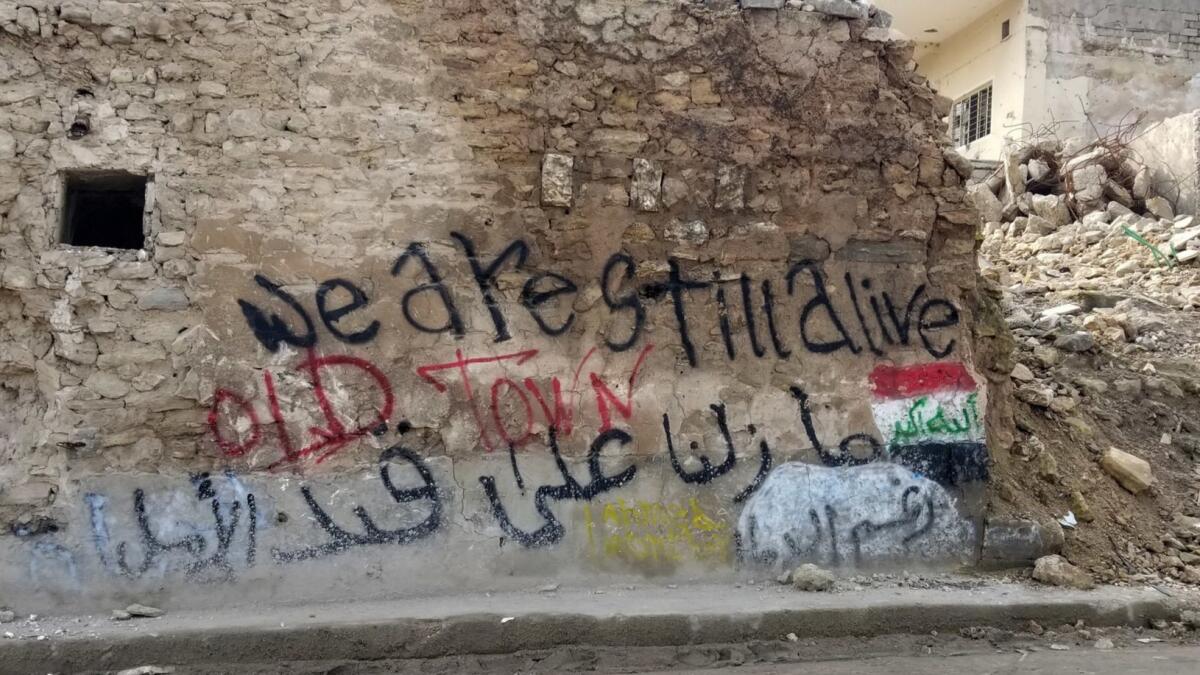

The riverfront neighborhood on the western side, a warren of alleyways and closely stacked buildings known as the Old City, was the site of the militants’ last stand. It was smashed.

After 277 days of combat, culminating in what then-Defense Secretary James N. Mattis called the use of “annihilation tactics” by the U.S.-led coalition, Islamic State’s three-year reign was over. Entire neighborhoods were destroyed, the bulk of them in west Mosul, with tens of thousands of people dead, many buried under the ruins.

For many, a year and a half later, the victory is still a Pyrrhic one, with authorities doing little to help those who had suffered under the extremists’ rule to rebuild their shattered lives.

It’s a scenario that is replicated throughout much of the country. But nowhere are the stakes higher than in Mosul, Iraq’s third-largest city, and nowhere are they so viscerally illustrated.

East Mosul represents one possible future, a city restoring its place among the country’s and the Arab world’s top metropolises. Old buildings are largely intact, and new buildings, including a more than 300,000-square-foot project called Golden Mall, are being built.

At the University of Mosul campus, students crowd coffee sellers on the street for a quick caffeine shot before class. One of the region’s top academic institutions, the university was under Islamic State control for two years before Iraqi forces took it back in January 2017; two months later, classes were already restarting. Now, more than 30,000 students have returned, professors say.

Nearby stores flaunt clothing and advertise wares proscribed during Islamic State’s rule, when the militant group’s harsh interpretation of Islam made even the most quotidian matters fraught with danger.

“Everything you see here, we couldn’t sell, let alone wear,” said Saad Mohammad, a university student and clothing store worker. He gestured toward stacks of Turkish-made stovepipe pants, colorful shirts and leather jackets.

“These pants, too long. Our beards were all wrong. They gave us trouble over everything.”

The sounds of traffic burble up outside the store in the upscale Zuhoor neighborhood, whose streets are lined with storefronts doing brisk business among throngs of pedestrians.

It’s the absence of pedestrians that is striking over on the west side, where many roads remain inaccessible. Those that were reopened were the work of activists, not the government, said Ahmad Ayoub, the mukhtar, or head, of one neighborhood in the Old City.

The western side has its history too. The Old City was where Mosul was first established, sometime after the fall of Assyria around 6th century BC. By the time Islamic State came, it had become the home of Mosul’s poorer residents, a worn-down warren of narrow alleyways snaking through creaking buildings.

It now represents the Iraqi state’s return to old habits: ineptitude, corruption and heavy-handed practices that in 2014 drove Mosul residents to welcome the extremists as liberators. Getting rid of the militants required the most intense urban fighting since World War II.

More than a year and a half after the offensive, tasks as urgent as removing millions of tons of rubble (much of it containing improvised explosive devices and other unexploded ordnance, not to mention body parts) are still confounded by problems both practical and bureaucratic.

One recent morning, a crew from the United Nations’ Mine Action Service and personnel from G4S, a private multinational security company, assembled at the Khaled bin Walid school in Mosul’s Old City.

‘One small mistake and you’re dead’: Defusing bombs in Mosul »

Inside the school playground, an armor-plated bulldozer scooped up debris, then strewed it over a space cleared in the center.

Four uniformed men stood in a line, then walked in step over the detritus in an awkward dance. A moment later, one of them raised his hand, gave a curt shout and pointed at a small lump of shaped metal — a piece of unexploded ordnance left over from the offensive. A demolitions expert came for a closer look, declared it safe and plucked it from the rubble.

“Belts, 155-mm artillery shells, canisters with [55 pounds] of explosives, fuses, small bomblets for drones,” recited one member of the demining team, pointing to a pile of ordnance recovered from the neighborhood in the previous three days.

A nearby church site, he added, contained 53 suicide vests.

Though everyone moved quickly, it was torturously slow work; at the present pace, the group expects the Mosul cleanup to take 10 years. And although the city’s home province doubled its share of the 2019 federal budget to 2%, the work is chronically underfunded.

The government also has not provided compensation to residents for war damage, leaving many unable to rebuild their homes, said Bashir Hussein Fathi, a onetime Old City resident and member of Iraq’s Communist Party.

“We think they’ll offer a small sum that’s a fraction of the value. It’s like the proverb: ‘From the camel they give you an ear,’ ” he said in a phone interview.

Like most others here, the neighborhood mukhtar Ayoub has nowhere else to go. He can’t afford the average $250 rent for an apartment on the east side. Other members of his family refused to help, he said, forcing him to return to the Old City and sleep in the ravaged husk of what was once his house.

Meanwhile, despite the presence of the U.N., donor countries and international organizations, the government has done little to rehabilitate the infrastructure.

In spite of those conditions, about 160 families have returned to Ayoub’s Old City neighborhood. Still, he said, hundreds more would follow once schools such as Khaled bin Walid were reopened.

Many families that have come back send their daughters to the Hafsa Girls School, where 25-year-old Nuha Samir Mohammad, who works with the demining service, plays a game to teach the children to not play with things they find on the street.

The children of Mosul talk about life under Islamic State. They saw things no child should see »

She lifts a laminated card with a picture of a goat.

“Goat!” the class dutifully recites. Mohammad nods and says, “We can touch a goat,” in a singsong voice.

She flips the card to a picture of an unexploded canister. “Canister!” shout the students.

Again, Mohammad nods. “This we shouldn’t touch.”

Many parties blame the lack of progress on the governor of Nineveh province, Nofal Akoub; he is accused of obstructing aid efforts while facilitating the sale of millions of tons of scrap metal at rock-bottom prices for the benefit of the Popular Mobilization Forces, the Shiite-dominated militias that took part in ridding the city of Islamic State.

A parliamentary investigative committee questioned Akoub about that deal, as well as real-estate repossession and the parceling off of state land. It has yet to release its findings.

Meanwhile, Mosul’s hard-won security after Islamic State is showing signs of fraying.

On Friday evening, a car bomb detonated in east Mosul as the head of the city’s National Security Service drove past. Two people were killed, including a 13-year-old girl, according to a police statement, and at least 10 others were wounded.

It was the second car bomb in as many weeks, after a string of attacks in rural areas outside the city attributed to Islamic State.

Hours later, civil defense crews had already cleaned up the site and the street’s rhythm was returning.

“Another explosion will happen and life will go on again. We insist on living our lives,” tweeted Bilal Mosuli, a nurse from the city. But he wondered how those who had placed the bomb knew of the security personnel’s movements.

“Till when will this joke continue? Till when do we keep on getting killed and our blood spilled?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.