It’s been 40 years since Iran’s Islamic Revolution. Here’s how the country has changed

Reporting from Tehran ‚ÄĒ It‚Äôs been 40 years since Iranians came together to topple the Shah.

Stirrings of opposition became apparent in 1975. The Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, who had been reinstalled in 1953 after the CIA helped overthrow democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, used tough and sometimes brutal measures to clamp down on dissent.

He replaced Iran’s two-party political system with a single political organization, downplayed the role of Islam in public life and used his internal security organization, SAVAK, to jail and sometimes torture opponents.

Street protests finally began in September 1978, when Iranians from all walks of life clashed with armed forces in Tehran, the capital.

Hundreds of lives were lost that day.

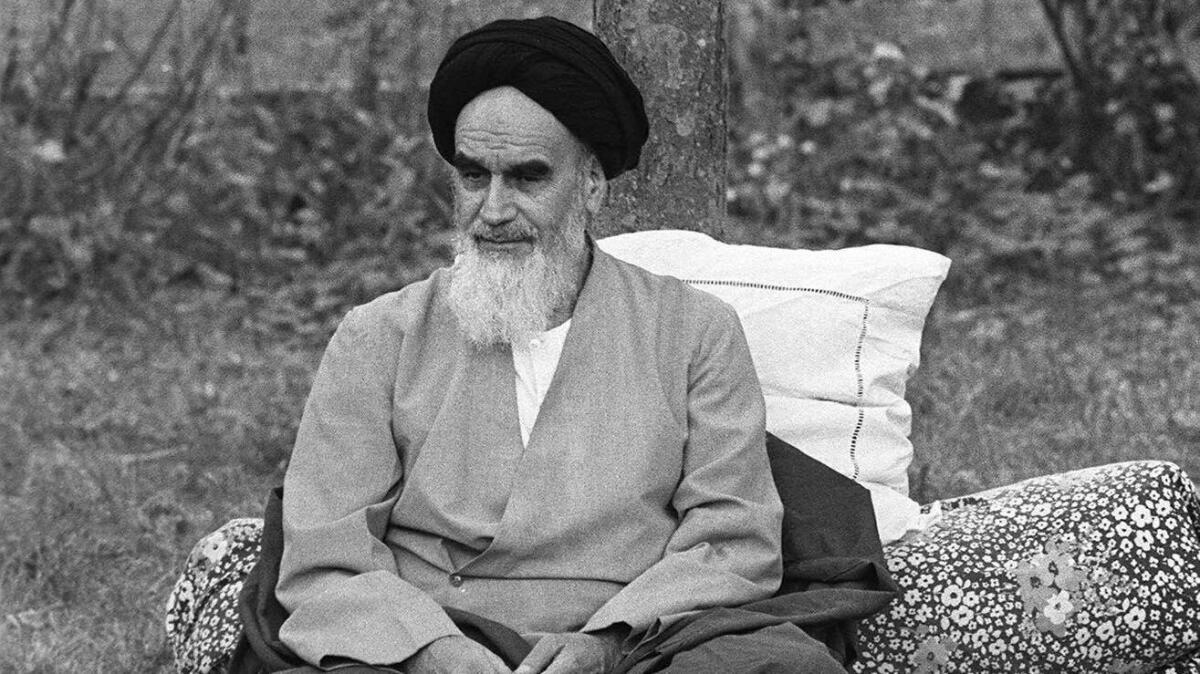

By late January 1979, after a series of bloody demonstrations, the Shah fled to Egypt. And on Feb. 1, hard-line Islamist cleric Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran from exile.

While leftists joined forces with conservative Shiites to dismantle the monarchy, Khomeini’s influence ultimately prevailed.

By June 1979, the secular, pro-American monarchy had been replaced with the Islamic Republic.

While several reformist and moderate politicians have been elected to govern Iran over the last four decades, in recent years, tough hard-line political and religious conservatives have become increasingly paranoid of Western influence and as a result have cracked down on people they perceive to be enemies of the state.

Here’s a look at how Iran has and hasn’t changed since Feb. 11, 1979, the date commemorated as the start of the revolution.

Social freedoms

Beginning in its early days, the Islamic Republic was opposed to anything it perceived as Western.

Women lost the right to divorce their husbands and were required to wear headscarves in public.

In many ways, freedom of expression has hardly improved over the last four decades.

In 2018, more than 7,000 political activists and others critical of the Islamic Republic were arrested, according to an Amnesty International study released last week.

More than half of those arrested had participated in antigovernment protests that swept Iran in 2017 and 2018.

‚ÄúThe scale of the arrests, imprisonment and flogging sentences reveal the extreme lengths the authorities have gone to in order to suppress peaceful protesters,‚ÄĚ said Philip Luther, Amnesty International‚Äôs director of research and advocacy for the Middle East and North Africa.

Population

Iran’s population is aging. Today, there are far fewer young people than before the revolution. That’s because economic instability and high unemployment rates have led to many young people holding off on starting families.

A rapidly aging population threatens to strain Iran’s welfare system. As a result, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has been urging women to have more children and says he wants the population to grow from 82 million to 150 million people.

Without a change, Iran’s median age is expected to rise from 27 to 40 by 2030, according to the United Nations.

To put it into perspective, in 1977 ‚ÄĒ two years before Iran‚Äôs Islamic Revolution ‚ÄĒ 44.5% of the population was 25 or younger. That trend continued after the revolution when officials began encouraging people to have more children.

As a result, the population doubled in almost a decade to 55 million, up from 27 million in 1968, according to data from the United Nations.

Then the Islamic Republic reversed course and implemented one of the most effective population control policies in the world.

The policy that led to a quick drop in fertility coupled with the strained economy makes the future look grim: As Iran’s working-class population continues to grow older, the country’s outdated public pension programs could face increasing strains.

Economy

In the 1970s, the unequal distribution of oil wealth hurt the Iranian middle class and rural poor while the elite reaped its benefits.

To reach out to the poor and dispossessed, including leftist elements, the revolution sought to limit the role of the private sector and distribute wealth more equally.

But things didn’t get much easier after 1979.

The revolution significantly disrupted Iran’s pattern of trade and investment as banks and insurance companies were nationalized. Problems were exacerbated in the 1980s due to the high costs of the Iran-Iraq war.

Fast-forward to 2018, economic mismanagement and corruption under Ayatollah Khamenei continues to plague Iran.

The unemployment rate now soars above 12%, according to official figures from Iran’s Statistical Center.

For those who hold college degrees, the situation is also dire. In 2018, more than 25% of people with bachelor’s degrees or beyond were jobless, according to several semiofficial news agencies in Iran.

Education

Education and literacy rates improved dramatically in the last four decades.

As of 2012, the literacy rate for both men and women in Iran was 98%, according to the United Nations. In 1978, more than 60% of women were illiterate.

Women also attend college at a higher rate than before the revolution. Now more than 60% of university students in Iran are female, according to that Statistics Center.

But that doesn’t mean that women’s participation in the labor force has improved. According to the World Bank, 17% of Iran’s labor force is female.

Environment

In the four decades since the revolution, lakes have dried up, lagoons have disappeared and wildlife has been threatened.

Although water mismanagement dates back before the 1979 revolution, when industries began to rely heavily on water and built a large number of dams, the situation worsened when the population doubled in size in the decade following the revolution.

Government officials‚Äô quest in the last 40 years to achieve food self-sufficiency without reforming the country‚Äôs inefficient agricultural sector ‚ÄĒ particularly wheat ‚ÄĒ kicked the water crisis into overdrive.

Environmental issues have become politicized in recent years following the arrest of several environmentalists in 2018 who had questioned the government’s agricultural policies.

Water scarcity, dwindling natural resources and government mismanagement sparked protests in western Iran in 2017.

Iran’s minister of agriculture, Mahmoud Hojjati, continues to boast about Iran’s agriculture production.

‚ÄúBefore the revolution, in 1979, the total agricultural crop was 26 million tons. Now it‚Äôs 122 million tons.‚ÄĚ

Air pollution in Iran is also a growing concern. According to a 2016 World Bank report, air quality in Iran ranks among the worst in the world.

While officials debate Iran’s environmental policies, the populace reels over the effects.

Saltwater Lake Urmia is drying up, and air pollution in the provincial capital of Ahvaz has led people to be hospitalized with breathing problems.

Mohammad Darvish, an environmental analyst based in Tehran, said some cities in Iran are actually sinking every year because there’s less water in the soil.

Times staff writer Etehad reported from Los Angeles and special correspondent Mostaghim from Tehran.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.