Can North Korea’s missiles deliver an atomic weapon to the U.S. mainland? Maybe

- Share via

Although recent missile tests indicate that North Korea has made advancements in missile technology, it’s unknown whether its missiles can deliver an atomic weapon to the continental United States.

“The bottom line is we don’t know,” said Ted Postol, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor emeritus of science, technology and international security. “I believe it’s unlikely they can deliver an atomic bomb to the United States at this time, but we can’t rule it out.”

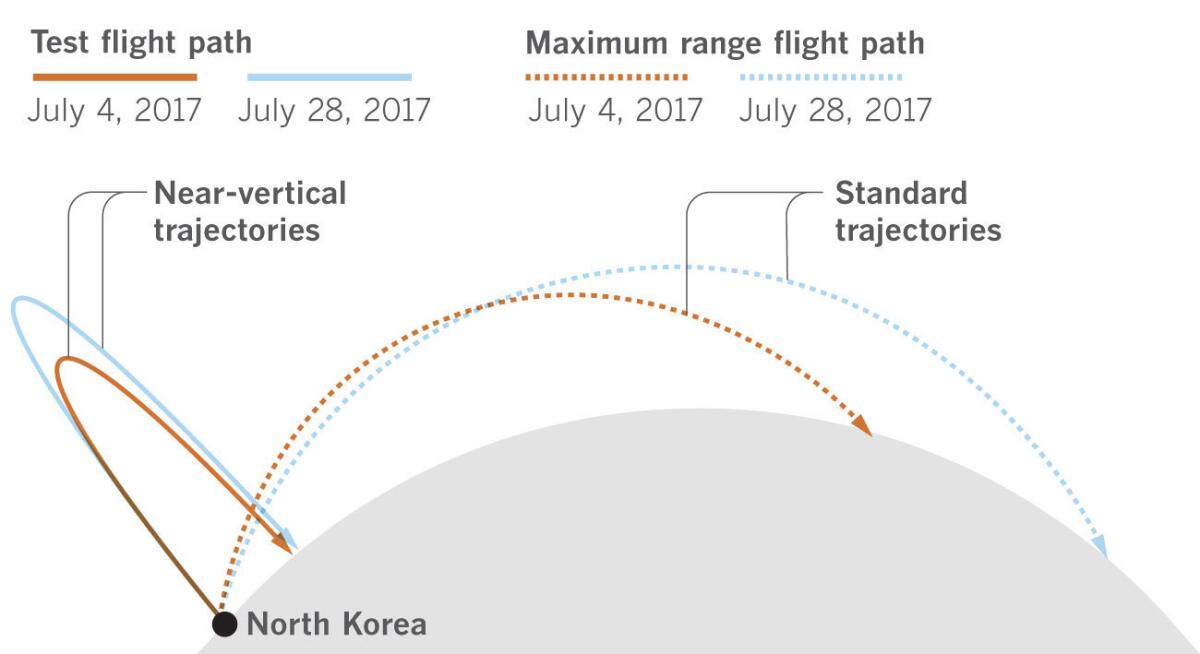

Missile trajectory and payload make a big difference

In most of its longer-range tests, North Korea has flown missiles on near-vertical trajectories with lighter than standard payloads. Once the weight of standard payloads and other factors are accounted for, the missiles may not be able to carry atomic bombs as far as test launches suggest.

To estimate the circumstances needed for a North Korean missile to reach the United States, Postol and two associates, Markus Schiller and Robert Schmucker, estimated the likely ranges of previous North Korean missile tests based on a standard trajectory and likely payloads.

Nodong Missile (May 1990)

Estimated payload: 1,100 to 2,200 pounds

Projected distance: 620 to 800 miles

Musudan Missile (June 22, 2016) Estimated payload: 1,400 pounds Projected distance: 2,000 miles

Hwasong-12 (Aug. 28, 2017)

Estimated payload: 1,100 pounds

Projected distance: 2,100 miles

Based on observed tests of the Hwasong-14 this year, an upgraded missile may be able to reach the United States with a payload weighing between 1,550 and 1,650 pounds. This would be possible only with the addition of extra motors that North Korea currently has. “It would be a major design improvement. But, I think they can do it. They’ve shown enough skill to do it,” said Postol.

The weight of the payload plays a huge role in the missile’s range, but nobody knows the weight of a North Korean warhead.

Hwasong-14 missile (July 4 and July 28, 2017)

Estimated payload: 1,550 and 1,650 pounds

Projected distance: 3,650 to 5,000 miles

What powers these missiles?

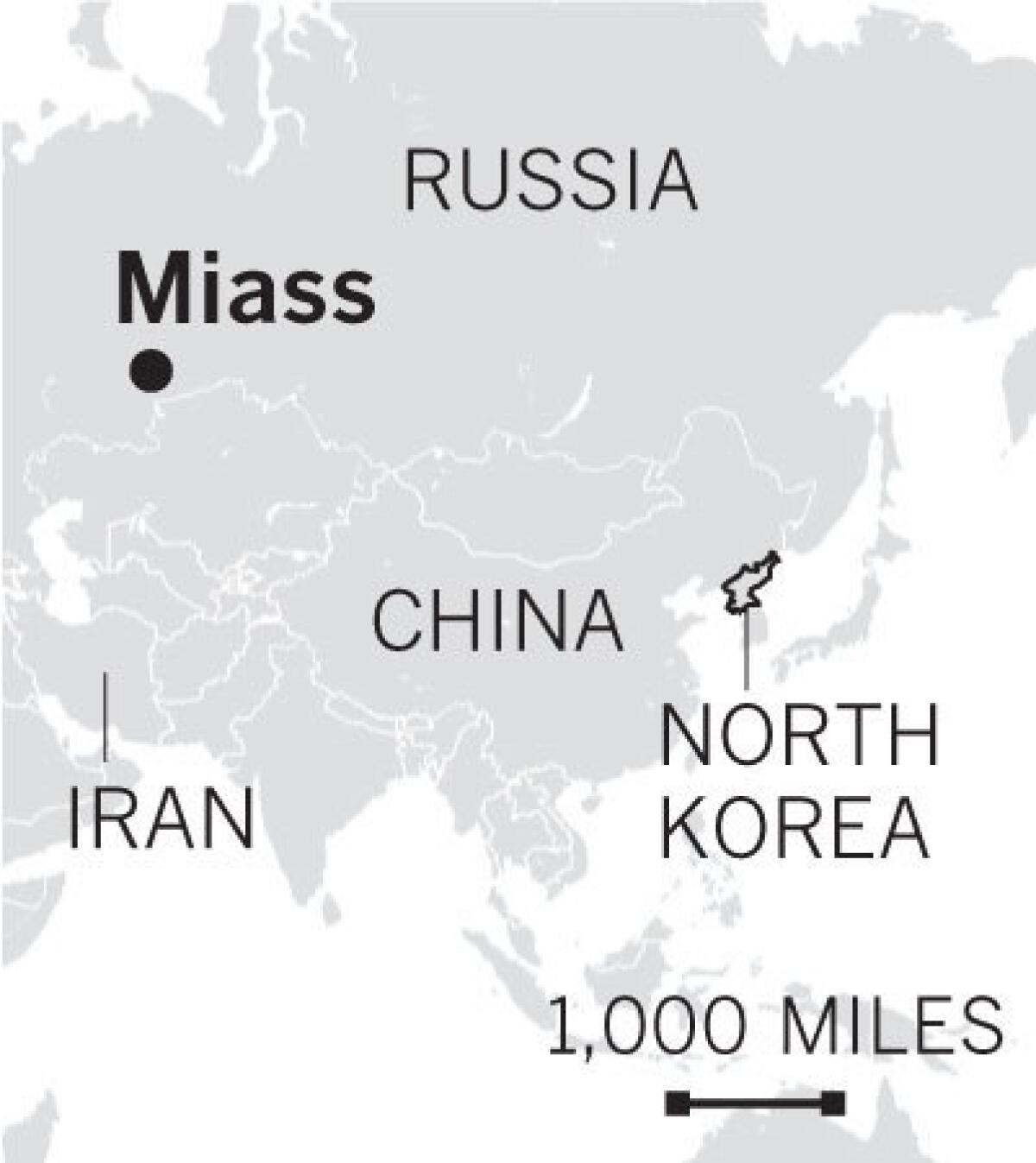

According to Schiller, founder of Germany’s Munich-based space and rocket consulting company ST Analytics, there is strong evidence that the early North Korean ballistic missile program was heavily supported by Russian engineers during and well after the 1991 Soviet Union collapse.

“At the time, giant transfers of missile systems and rocket components occurred,” he said.

Postol believes that Russian rocket engineers from the Makeyev institute in Miass, Russia, the organization that designed the most advanced Soviet rockets during the Cold War, migrated to North Korea during the Soviet Union’s economic collapse.

“The North Koreans were willing to give them money to sell them these components. This was a catastrophic hemorrhage of Russian rocket components that happened without the knowledge of the central Russian government,” he said.

The engines in North Korean missiles, including the Hwasong-12 and 14, are extremely complex. Though unable to manufacture and engineer much of the technology on its own, North Korea adapts and modifies Russian designs to build its arsenal.

“A modern world where very advanced pieces of technology like rocket engines can be adapted for different purposes creates an environment that allows for the serious proliferation of long-range missiles from North Korea,” he said.

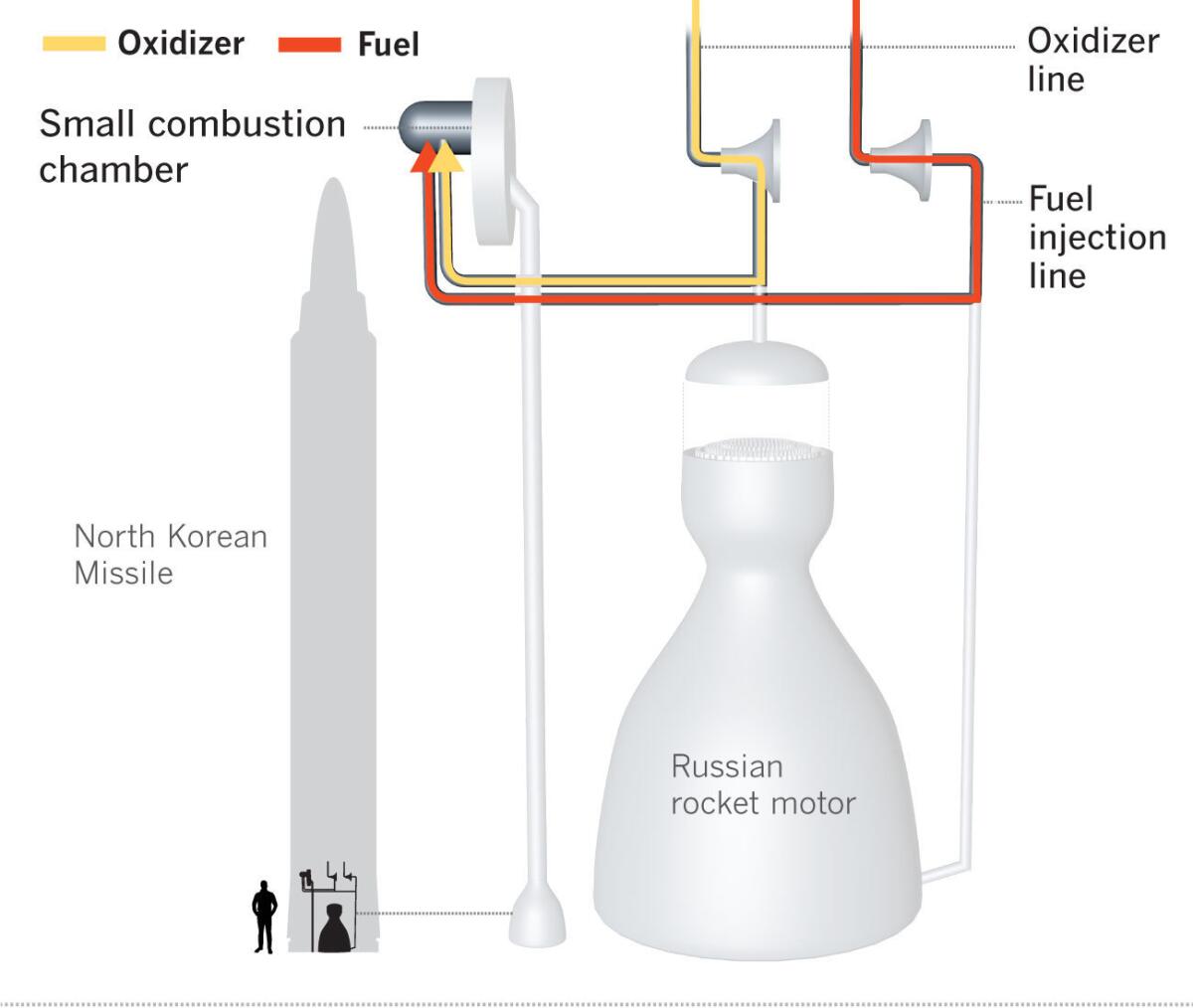

How Russian rocket engines work

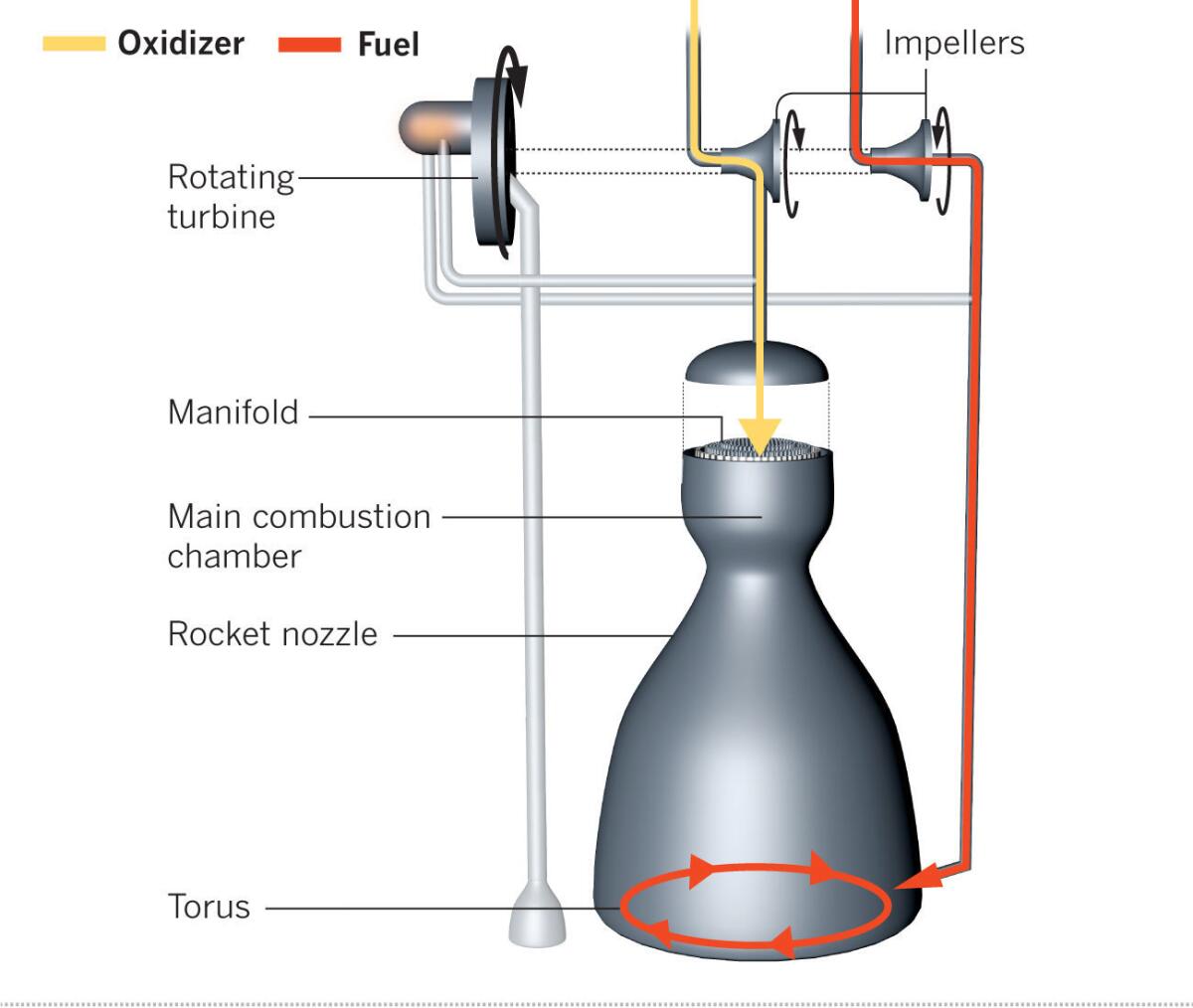

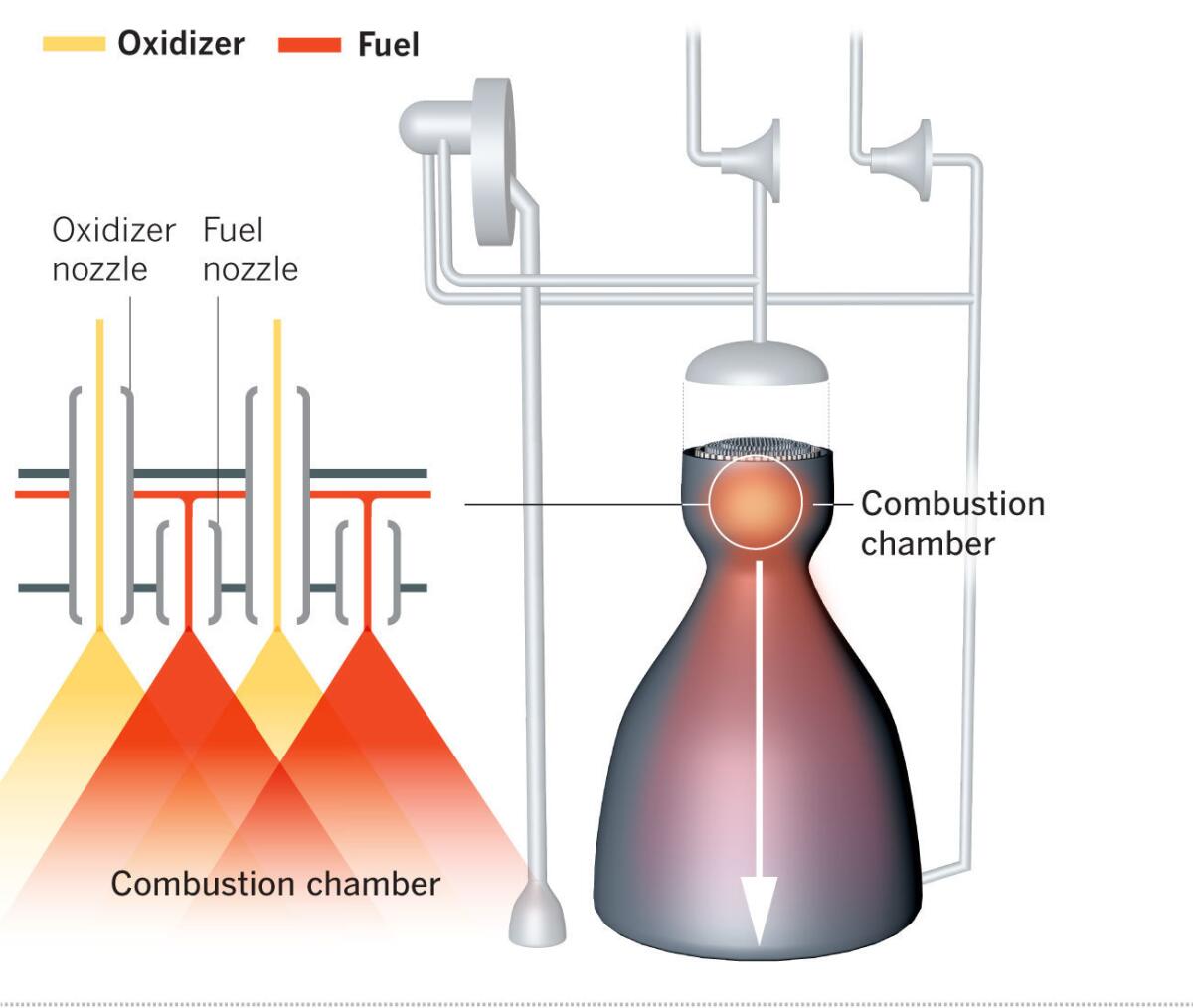

Fuel and nitrogen tetroxide, an oxidizer that enables combustion, is forced into a small combustion chamber.

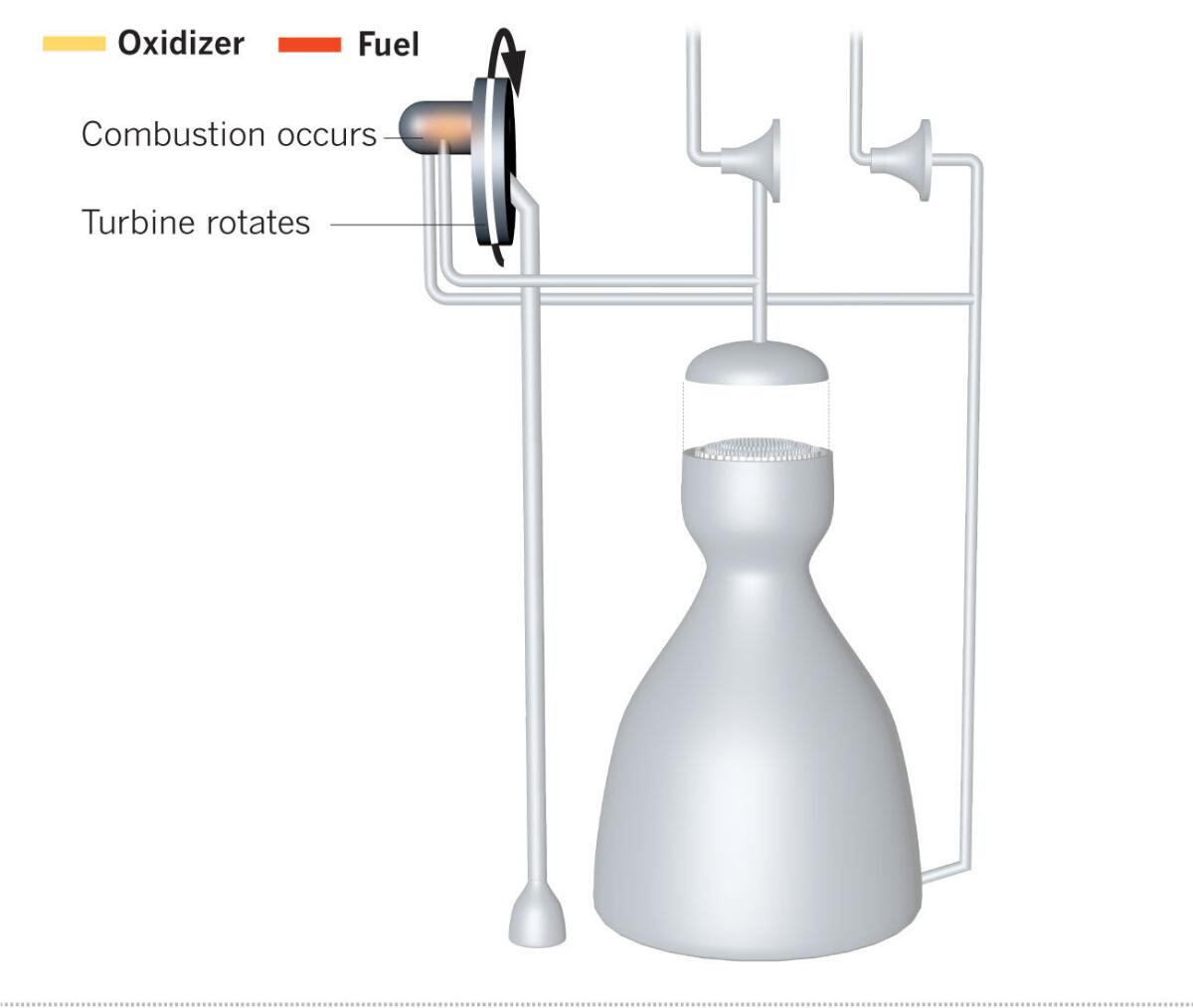

To start the rocket motor, fuel and oxidizer combust in the small combustion chamber, powering a turbine that makes 10,000 to 30,000 revolutions each minute.

The turbine powers “impellers” — propellers that suck fluid in and accelerate it outward at high pressures. Oxidizer is pushed to the top of the cone-like rocket nozzle, while the fuel is forced into a circular tube — known as the torus — at the bottom of the rocket nozzle.

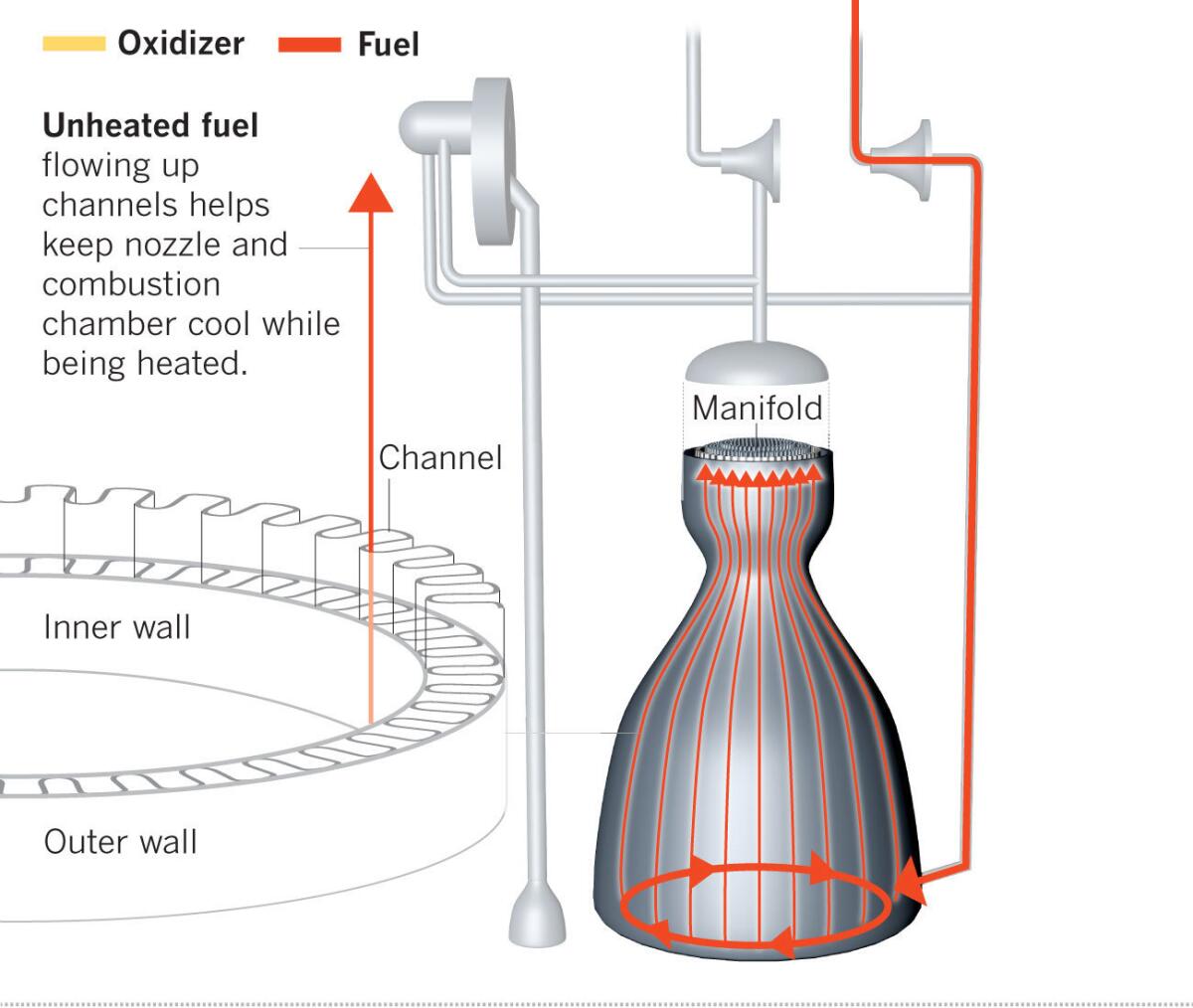

Unheated fuel is injected at high pressure into bottom of the rocket nozzle and funneled up channels of corrugated metal between the nozzle’s inner and outer walls. The unheated fuel flowing up channels keeps the nozzle and combustion chamber from melting. The fuel is heated as it travels upward. Once it reaches the top, it is pushed into the fuel manifold.

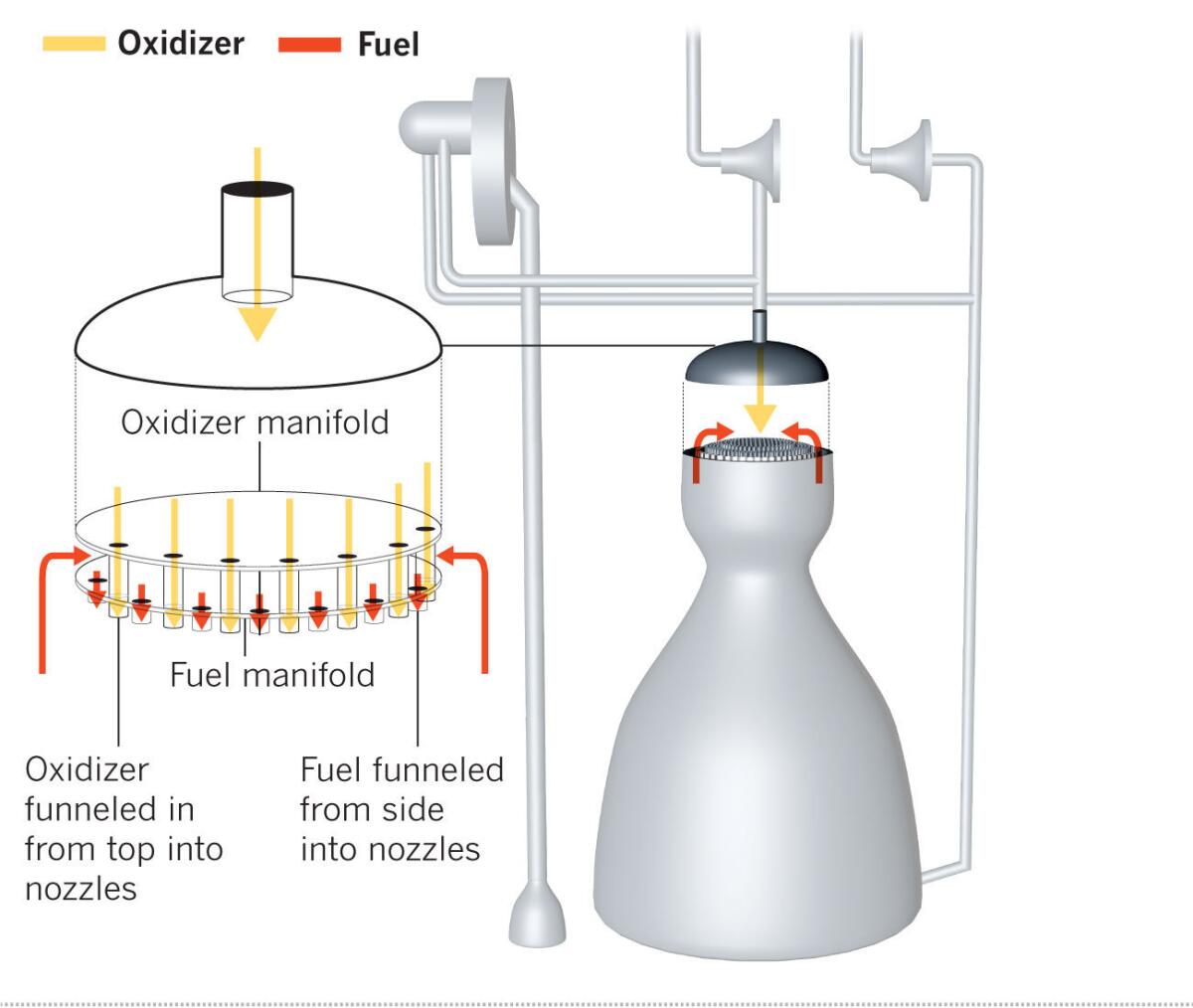

Fuel and oxidizer are sprayed into the combustion chamber at angles designed to maximize mixing. Combustion occurs instantly.

Key to the rocket’s success is the precisely controlled mixing of rocket fuel and oxidizer. Do it even slightly wrong, and the rocket can explode prematurely.

Fuel and oxidizer are pushed into the manifolds at 25 gallons per second. Between 250 and 1,000 nozzles within the manifolds keep fuel and oxidizer separated to prevent premature combustion.

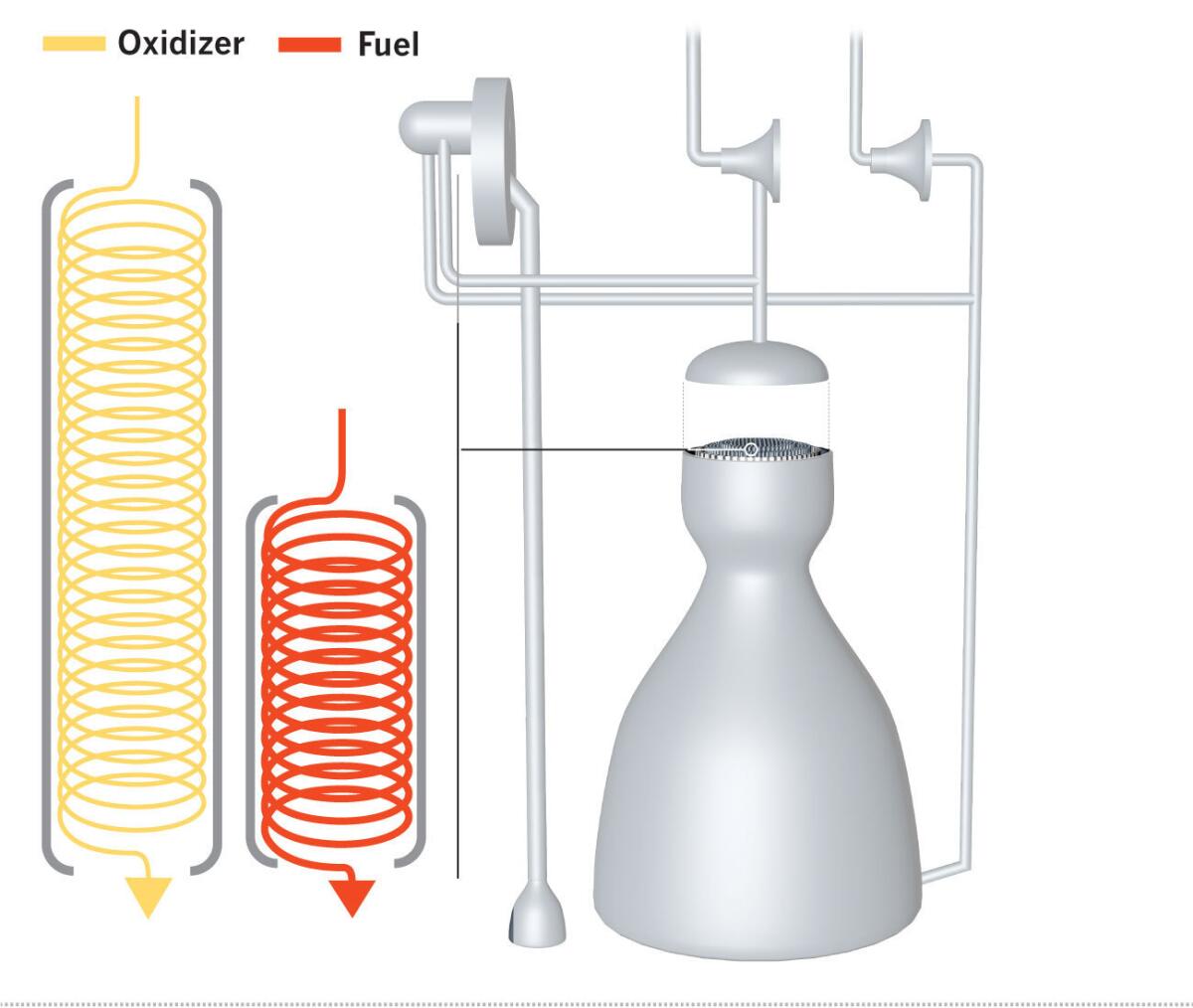

Inside the nozzles, fuel and oxidizer are forced into a spiral motion to increase the lateral pressure and velocity.

Fuel and oxidizer are sprayed into the combustion chamber at angles designed to maximize mixing.

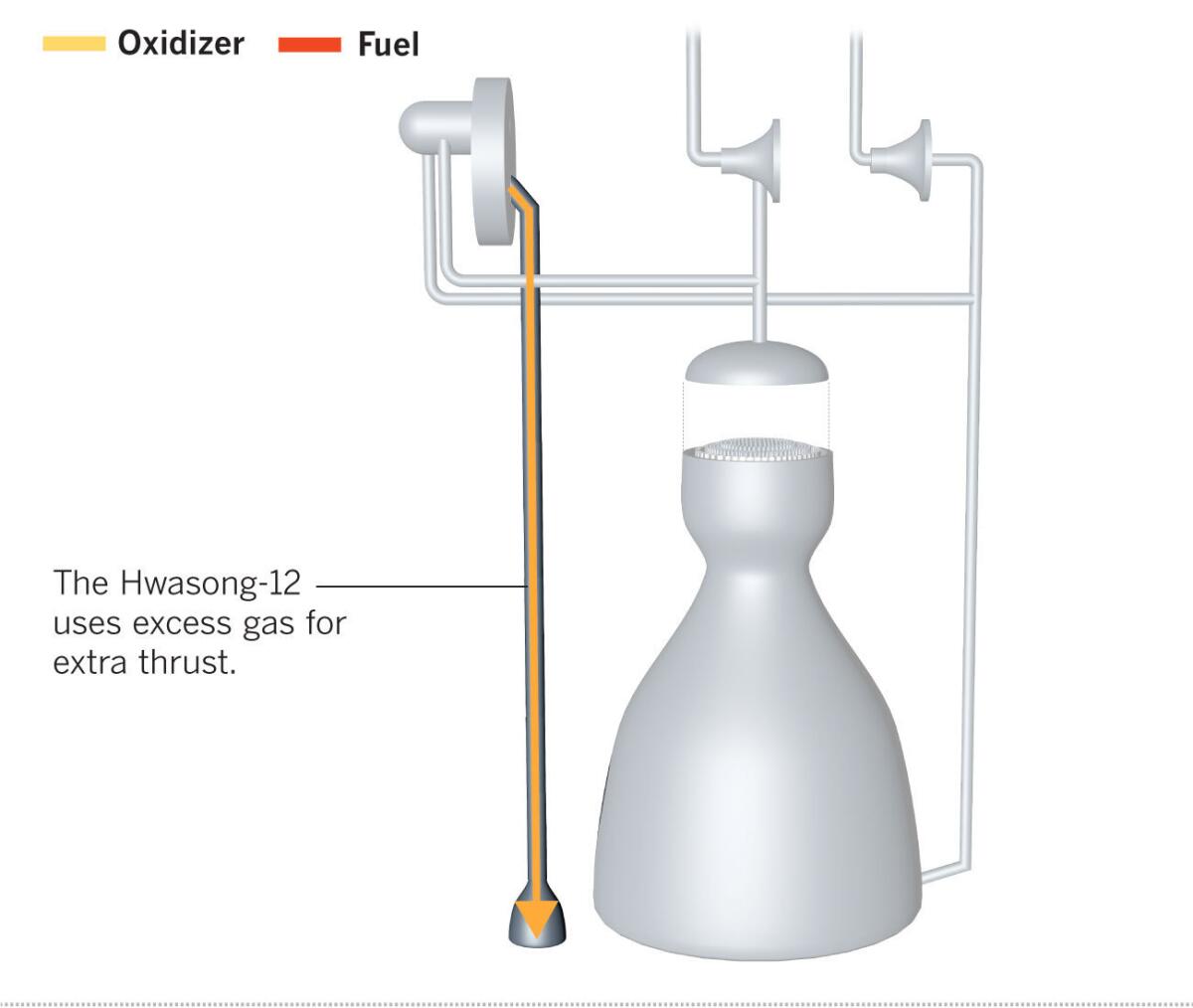

Excess gas from the small combustion chamber is expelled into the environment and adds to the motor’s thrust.

Failures and recent successes

North Korea has had some notable failures in its missile program. The Musudan missiles failed nearly all of their flights.

“We would see North Korea moving Musudans around,” said Postol. “They hadn’t been tested though. Once they started to fly it, it failed almost all the time.”

“They made a bad design choice in this case and had a large number of failures,” he said. “Maybe they hoped to get their manufacturing ability to a higher level. They were wrong.”

The Hwasong-12 and 14, unlike the Musudan, have been very successful. Out of eight launches, there have been only three unconfirmed failures.

These recent increase in missile launches — and the apparent higher performance of these missiles — seemingly indicate a vast improvement in North Korea’s nuclear missile capabilities.

However, Schiller agrees with Postol that these capabilities could not have occurred without Russian motors.

“For a first-generation rocket, dozens of launches and over 10 years of development are typically required. At least five more years of development and 10 more launches are usually needed to verify a weapon is ready for war,” he said.

“North Korea’s highest priority is to survive as a state,” said Postol. “They are abundantly aware that the U.S. has a history of trying to destabilize countries that the U.S. doesn’t like. They’re saying, don’t try it with us.”

“They want to look dangerous to deter any foreign interference,” said Schiller. “That’s all they really want.”

Additional sources: Robert Schmucker, Schmucker Technologie, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

ALSO

A Somalia bombing killed hundreds; officials figure it must have been Shabab extremists — again

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.