Charlie Hebdo shooting: The victims

- Share via

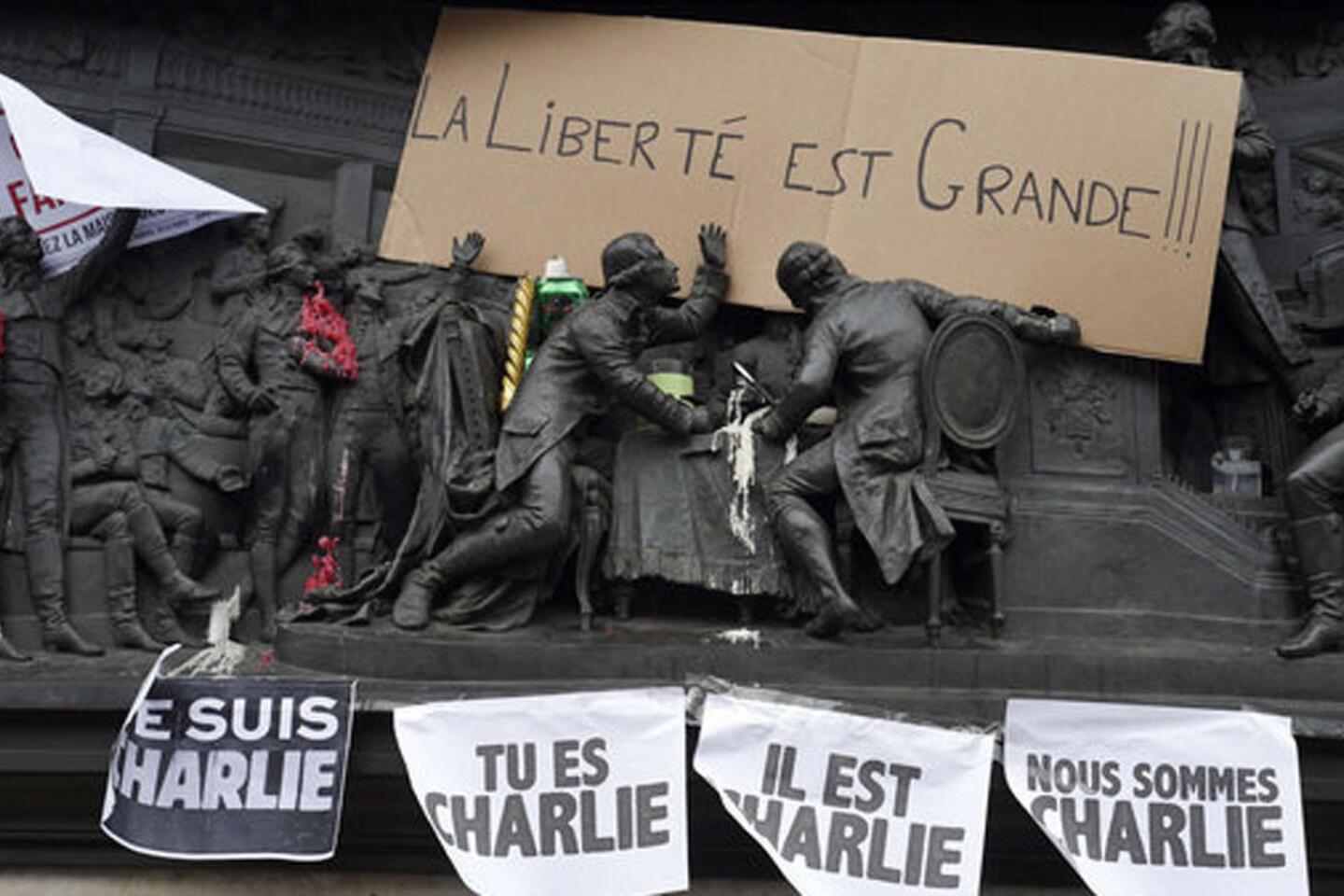

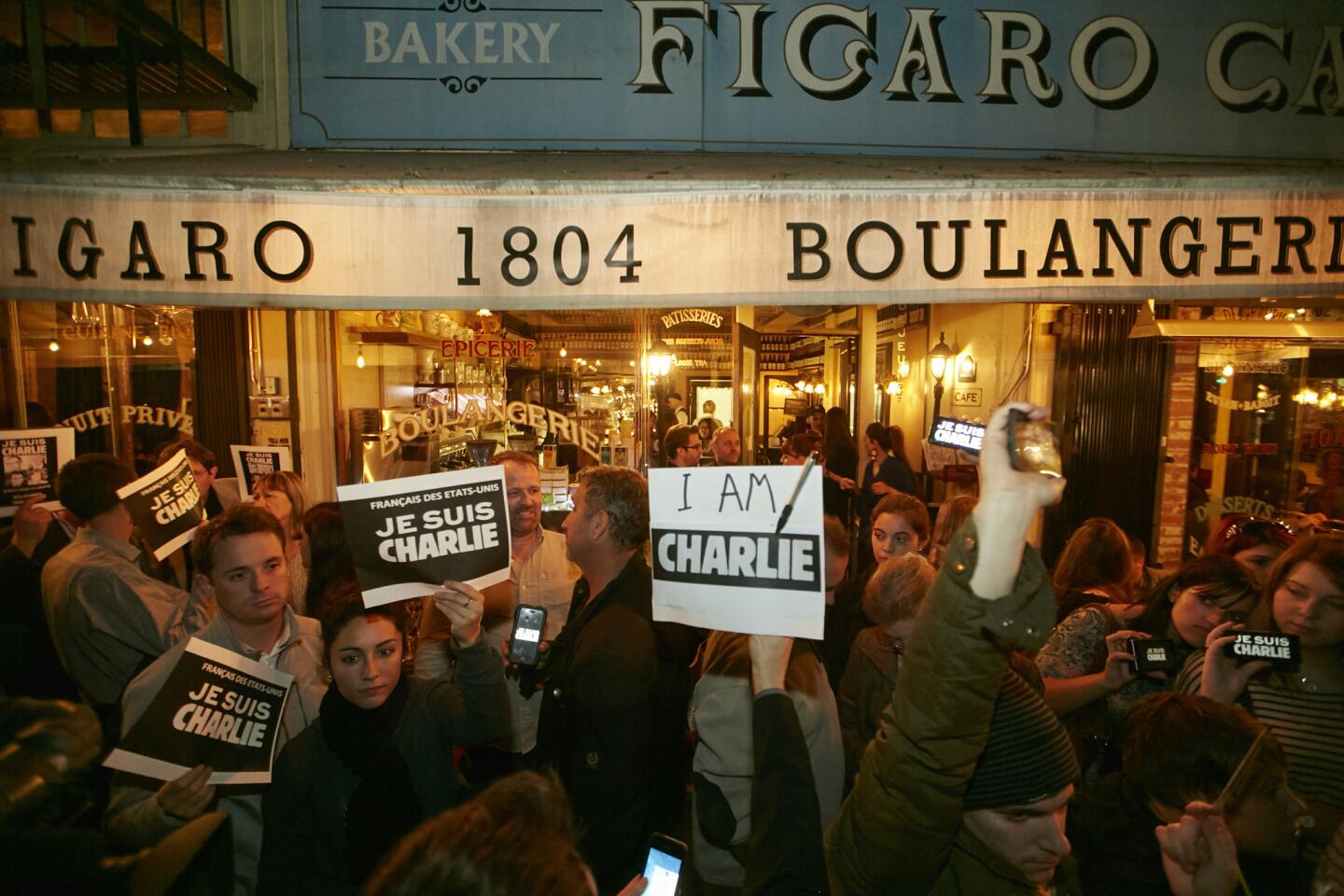

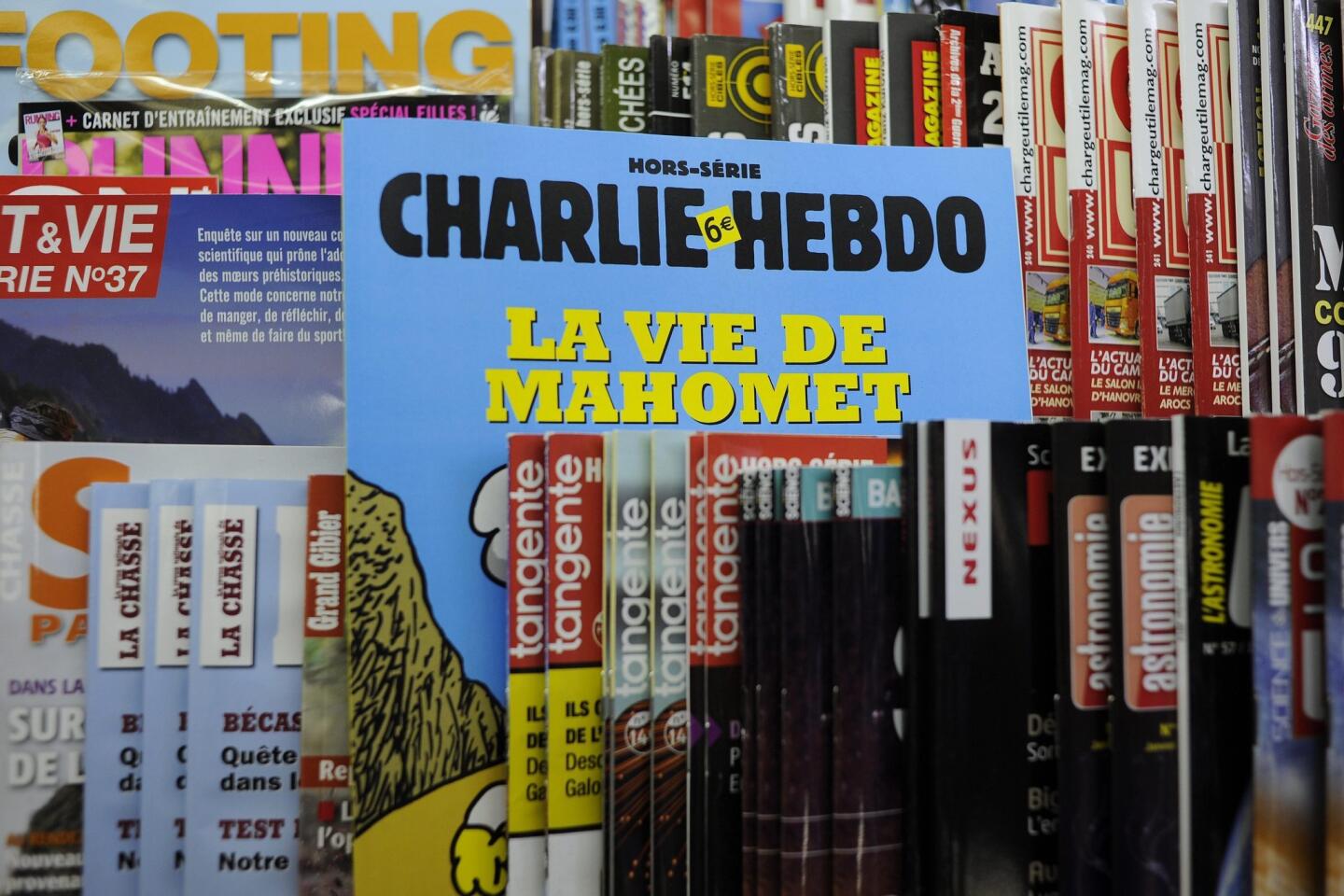

Twelve people were shot and killed Wednesday in the center of Paris after masked gunmen stormed into the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which has published controversial depictions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

The dead included eight staff members of the magazine as well as two police officers, a visitor and a maintenance man. Among the victims was the magazine's editor, Stephane Charbonnier -- widely known by his pen name Charb, according to police.

Here are profiles of the confirmed victims so far.

More coverage

Franck Prevel / Getty Images

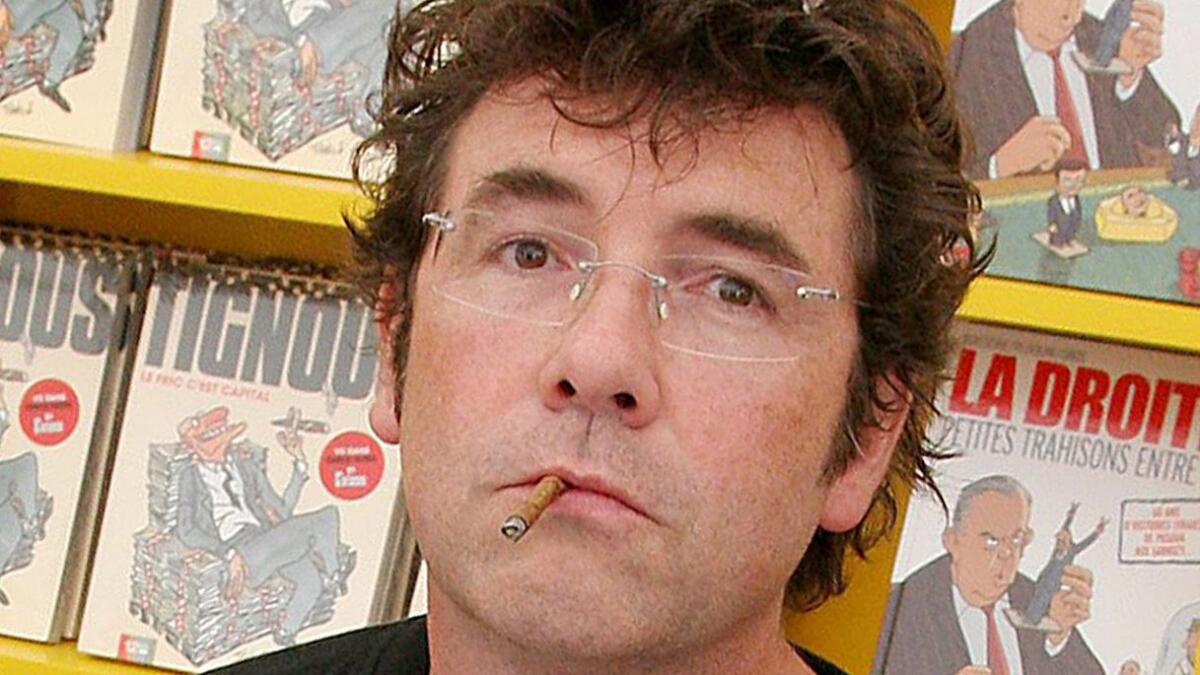

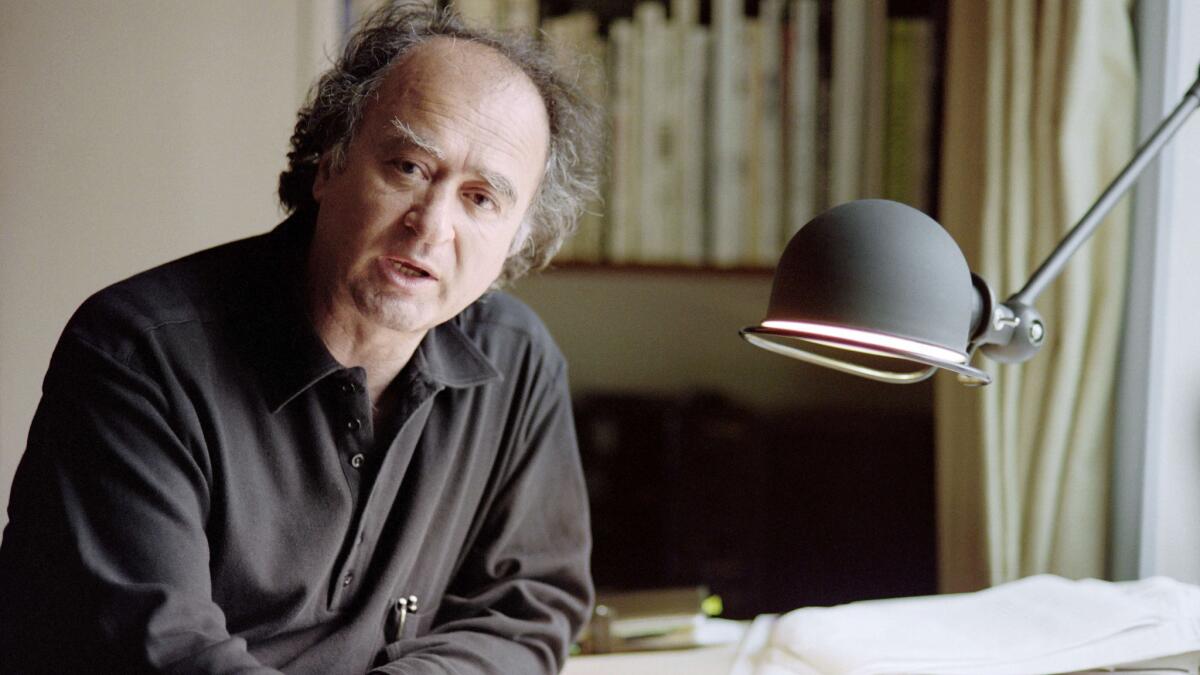

Stéphane Charbonnier, the soft-spoken editor of Charlie Hebdo and a cartoonist popularly known as “Charb,” has held his position since 2009.

“It just so happens I'm more likely to get run over by a bicycle in Paris than get assassinated,” Charbonnier said in a 2013 interview with the Los Angeles Times at his office in Paris, which lacked signage after a series of threats and attacks against the left-leaning paper.

Charbonnier conceded that it would be harder to do his often-incendiary work if he had a family to worry about. But he stood on principle.

“If one person is injured or killed, it doesn't mean all of France will be put on its knees,” Charbonnier told The Times. “It's not Islam attacking France, it's one person attacking another person, that's all.… If a small group of terrorists, however small it is, starts to dictate its law to newspapers in France or elsewhere, that would really be a shame.”

Charbonnier added: “It's not exactly our drawings that have power, it's our stubbornness — a stubbornness to continue doing what we feel like doing, through drawing.... It comes from the fact that I have nothing else. The only thing we have is our freedom of speech. If we give up on that, we'd need to change fields. Do other things.”

Frederic Boisseau was a maintenance worker at the Charlie Hebdo offices. He was in the reception area when gunmen stormed into the building Wednesday, Le Monde newspaper reported.

His death was confirmed by his employer, Sodexo, which provides janitorial and other services to the 11th arrondissement building where the publication is headquartered.

Boisseau was married and the father of two children, ages 10 and 12, Le Figaro newspaper reported.

He had worked for Sodexo for 15 years. “We all share the feeling that it's intolerable that one of our colleagues has lost his life in such tragic and unjust circumstances,” Sodexo Chief Executive Michel Landel said in an email shared by the paper on its Twitter account.

Franck Brinsolaro was a police officer assigned to protect Charlie Hebdo’s editor, Stephane Charbonnier.

A member of France's Protection Service, which provides security for important people and institutions, Brinsolaro held the rank of brigadier, which is equivalent to a sergeant.

His wife, Ingrid, is the editor in chief of L'Eveil Normand, a weekly news publication in the northwest of France. They have two children, according to a report from the French radio station Tendance Ouest.

Brinsolaro was shot and killed inside the Charlie Hebdo offices, authorities said.

Joel Saget / AFP / Getty Images

Jean Cabut, known as Cabu, was born Jan. 13, 1938, in Châlons-sur-Marne, a small town east of Paris, according to the Bibliotheque Centre Pompidou, a public library in Paris.

“I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember,” Cabut said, according to the library’s biographical sketch. He began his work at least as early as age 13, when he drew for his school paper and local daily paper, L’Union, for whom Cabut worked until 1961.

Cabut served in the military in the 1950s during Algeria’s fight for independence from France. The brutal conflict later fed his “anti-militarism,” Cabut told the French magazine L’Edition du Soir. The artist would base one of his characters on an official he met during the war.

After leaving Algeria, Cabut went on to draw for various publications, including the controversial and highly offensive French satirical magazine “Hara Kiri”—named after a Japanese form of suicide that involves plunging a knife into the stomach—from 1962 to 1972. From 1977 to 1987, he worked on the youth-oriented TV show “Récré A2.”

Cabut helped to relaunch the Charlie Hebdo title with some friends in 1992, according to the library’s biography of the artist, who continued work for a satirical publication called “Le Canard enchaîné,” the chained duck.

The French newspaper Le Monde said Cabut’s death “leaves a gaping void in the world of cartoonists” and that Cabu was “one of the giants of the genre.”

Elsa Cayat, the only woman among the 12 victims, was a psychoanalyst and a columnist for Charlie Hebdo, French news reports said.

She wrote a book on gender relations called “One Man + One Woman = What?” and another with an unprintable title about sex and desire.

Richard Brunel / EPA

Philippe Honore was a veteran cartoonist who tackled topics including foreign affairs, popular culture and sports.

He drew for Charlie Hebdo for more than two decades and was published in other prominent French papers, including Le Monde and Liberation.

His was the last illustration tweeted by Charlie Hebdo before the attack. The cartoon, posted Wednesday, is a satirical depiction of Abu Bakr Baghdadi, leader of the extremist group Islamic State.

Born in the central city of Vichy, Honore was a self-taught artist whose first works were published in Sud Ouest, a regional daily newspaper, when he was 16, according to Le Monde.

He developed a signature style that often consisted of a single panel in black and white, with minimal captions.

In the thick of the doping scandal that hit the world of competitive cycling, Honore created a cartoon showing a couple on an old-fashioned tandem bike captioned: “In that era, it was without doping.”

Noted for his white hair and beard, Honore was regarded as a genial, low-key personality among France's media elite.

Christophe Abramowitz / France I / EPA

A noted Keynesian and political maverick, he was a widely read public figure who also appeared frequently on French television and radio, debating about economics and politics. He was a regular contributor to Charlie Hebdo.

Maris’ political beliefs could be difficult to pigeonhole. He was sometimes categorized with “alter-globalization” advocates, who believe in some forms of global cooperation but oppose many of the effects of economic globalization. At the same time, he was lumped together with environmentalists and the Green party. He was also a member of the governing board of the Bank of France.

He told Le Monde in September that French President François Hollande "is perhaps still on the left, but he's no longer socialist. The socialist dream, which consisted of prolonging the great revolution of human rights and freedom on a social scale, has vanished with him."

He added, "If it's not dead, the left is quite sick."

Maris' many interests also included the novels of the controversial French author Michel Houellebecq, on which he recently published a book exploring the economic dimensions of the novelist's body of work.

"Capitalism is a system based on immaturity and it can't last forever," Maris told the Nouvel Observateur last year. "It's only been 200 years, after all. That's nothing on the timeline of mankind."

Ahmed Merabet served at a police station in Paris' 11th arrondissement, the neighborhood where Charlie Hebdo’s offices are located, French news reports said.

His death was captured in video broadcast on French television and widely shared on social media sites. The video shows one of the gunmen shooting Merabet outside the magazine offices, then approaching the writhing victim to fire a fatal shot at point-blank range.

He leaves behind a girlfriend.

Mustapha Ourrad, a native of Algeria, was a copy editor at Charlie Hebdo.

An orphan, he immigrated to France when he was 20 and went to work in the publishing industry, according to Le Monde.

A self-taught man, Ourrad was known for his erudition – he was a Nietzsche fan -- and also for his self-mockery, the newspaper reported.

Roland Amadon / EPA

Michel Renaud was a founder of a travel festival in the Auvergne region in central France and was reportedly visiting the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris on Wednesday.

A former journalist for Le Figaro and Europe 1, he left the profession and became a travel expert. He helped to create Rendez-vous du Carnet de Voyage (Travel Book Rendez-vous) , a biennial expo of travel writers and enthusiasts who gather in the central city of Clermont-Ferrand.

Renaud was at the Charlie Hebdo office with a colleague to meet cartoonist Jean Cabut, who had previously been a guest of honor at the festival, France 3 TV reported.

Renaud’s colleague, Gerard Gaillard, survived the attack by hiding under a table, according to a report on the Radio France website.

Renaud also worked in local politics, serving as communications director for Roger Quilliot, a longtime mayor of Clermont-Ferrand, and as deputy chief of staff for Serge Godard, another city mayor.

Tim Somerset / EPA

The father of four drew his first cartoon when he was about 13, according to remarks published by the French Embassy in Colombia when Verlhac visited the country in 2010. His first published drawing was done for a striking labor union to which his father belonged.

“My father worked nights at the post office,” Verlhac said, according to the embassy. “He went on strike to warn about the destruction of public services, a fight that still exists today, and he wanted a poster.”

Verlhac went on to become a prominent satirist for Charlie Hebdo and other publications. “The best cartoons give rise to laughter, thought and set off a certain kind of shame,” Verlhac was quoted as saying.

Before his death, Verlhac was preparing to publish a new book about prisons with Dominique Paganelli, who called Verlhac a man of “extreme kindness” and “tremendous tenderness,” according to the French newspaper Le Figaro.

AFP / Getty Images

Georges Wolinski, a cartoonist at Charlie Hebdo, was widely known for his racy and sometimes transgressive illustrations that earned him admiration among French journalists and the public at large.

His drawings encompassed a wide range of subjects, but he specialized in contemporary sexual mores, with a focus on women, and current affairs. He was also a published author, with a new graphic novel, "Le Village des femmes," that was released in September.

Wolinski , or "Wolin" among friends, joined Charlie Hebdo in 1969 and later became an editor of Charlie Menseul, a monthly publication. He also drew for several other French publications, including Le Nouvel Observateur, L' Humanite, Paris Match and the Journal du Dimanche.

He once said when asked about death: "I want to be cremated. I told my wife: You will throw my ashes in the toilet, that way I will see your ass every day."

Born in Tunisia, Wolinski was Jewish and lived in North Africa until the age of 13.

"My job is to look for ideas," he told L'Humanite in 2011. "I've spent all my life looking for ideas like a pig looks for truffles. To search means being able to avoid thinking, re-assessing, being scared. It's reassuring to search."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.