Trying to find U.S.-Japanese harmony amid the discord of a death in Okinawa

- Share via

Reporting from Okinawa, Japan — Leah Siangco, a 34-year-old California native, and her husband, a pastor, put out a call recently to members of their congregation, Neighborhood Church Okinawa. Join us, they said, for a silent memorial along Route 58, a busy thoroughfare on the southern Japanese island where tens of thousands of American troops are based.

The couple felt moved to action by their faith, they said, disturbed by news that a former U.S. Marine-turned-civilian contractor had been arrested by Japanese police and acknowledged abducting and killing a 20-year-old local woman.

So they prepared some posters at the church office, with simple messages in English and Japanese like “We mourn with Okinawa,” alongside a heart formed by the U.S. and Okinawan flags. The idea was to stand by the road with the signs, heads bowed in prayer, to express their grief and solidarity with the local community.

Almost anywhere else, such a gathering would be considered a kind and natural — even routine — neighborly gesture after a brutal and senseless crime. But until they walked out to the highway, the Siangcos felt extremely anxious about how they’d be received. “I was super nervous,” said Leah Siangco, who hails from the city of Orange. “Almost sick to my stomach.”

Because Okinawa is not just anywhere. A diminutive tropical island paradise ravaged in the final months of World War II, Okinawa has long been a nexus for U.S.-Japanese cooperation — and conflict.

Following Japan’s surrender, Okinawa found itself transformed into one of the most extensive overseas U.S. military installations in the world. In 1972, Washington handed administrative control to Tokyo, but the islands have continued to host a vast network of bases used by the U.S. Army, Air Force, Navy and Marines as well as Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.

Over the last seven decades, Americans and Okinawans have worked together, worshiped together and wed one another, forging a codependent community even as politics have cycled through episodes of confrontation and collaboration.

But anti-base sentiment has been festering in recent years, fed by concerns over the environment, economy and crime, among other issues. In the aftermath of the homicide, many here are wondering whether the situation has reached a tipping point.

“We are at a new low,” said Robert D. Eldridge, an American scholar who has researched Okinawa extensively and served as a senior public affairs official for the Marines from 2009 to 2015. “In a nutshell, it’s unsustainable here ... operationally, strategically, fiscally and politically.”

The case has put Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, a staunch proponent of strengthening defense ties with Washington as China’s military flexes its muscles, in a tight spot.

U.S. officials have scrambled to try to contain the damage, with President Obama and Defense Secretary Ashton Carter offering apologies and Marine Lt. Gen. Lawrence Nicholson, the top commander in Okinawa, announcing a monthlong mourning period, a temporary curfew and new restrictions on drinking off-base.

Okinawa politicians, though, are not satisfied, passing a resolution calling for Marines to withdraw completely from the island prefecture. Anti-base activists, meanwhile, have ramped up their protests and stepped up pressure on Abe to cut, at long last, what they say is Okinawa’s disproportionate burden for hosting U.S. troops in Japan. They are trying to organize a large rally on June 19.

But many ordinary islanders — Americans and Okinawans — say the increasing polarization is in neither side’s interest. The swirl of events has left them wrung out, suspended in a matrix of frustration, sadness and uncertainty.

Christian Siangco, the pastor, said he fielded numerous phone calls warning him that his plans for a silent memorial could be construed as being anti-base, and suggesting it might be better to lie low.

“But I had just been preaching on standing firm in one’s faith,” said Siangco, a retired Navy chief petty officer. “Someone needs to stand up for hope.”

+++

Rina Shimabukuro vanished in late April while out for an evening walk. It took three weeks for police to find the young woman’s corpse, dumped along a bend in a wooded area in the village of Onna.

Authorities found the body after questioning Kenneth Shinzato, a 32-year-old ex-Marine who was working as a computer and electrical contractor at Kadena Air Base. Security camera recordings showed his car near the site where Shimabukuro disappeared. Local media reports say she was sexually assaulted.

The case has sparked incredulity not least because Shinzato, a civilian employee born Kenneth Franklin Gadson, seemed to personify the close relations in Okinawa between Americans and Japanese. Married to a local woman and the father of a newborn, he had taken his wife’s last name and lived off-base.

The case immediately dredged up memories of a litany of crimes committed by U.S. servicemen in recent decades, from the rape of a 12-year-old girl by three Americans in 1995, to robberies and a March incident in which a U.S. Marine pleaded guilty to raping a woman he found asleep in the corridor of his hotel. This past weekend, a 21-year-old Navy petty officer second class was arrested on suspicion of drunk driving after crashing her car into two vehicles while traveling the wrong way on Route 58.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

June 7, 6:28 a.m.: This article said that a U.S. Marine pleaded guilty in March to raping a woman he found asleep in the corridor of his hotel. The man was a U.S. Navy sailor.

------------

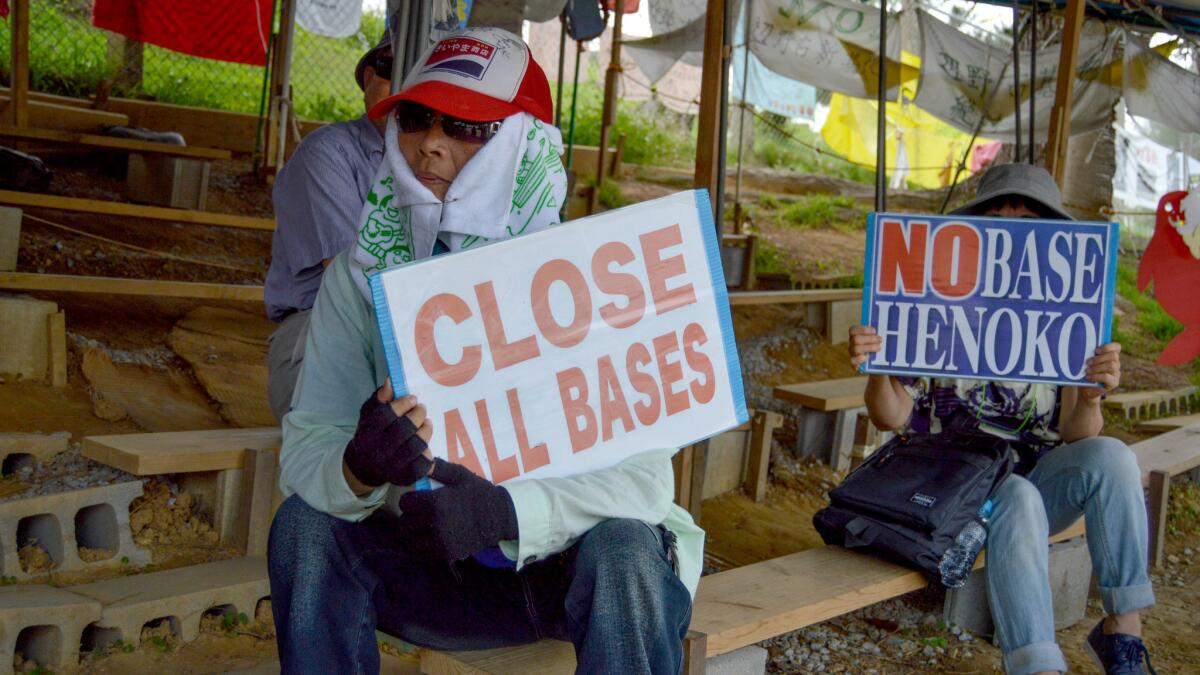

Though Shinzato was no longer a member of the military, that distinction matters little to many Okinawans. “He works on the base. Before, he was a Marine,” said Hiroji Yamashiro, 63, an activist who has spent 700 days protesting plans to expand the Marines’ Camp Schwab in the village of Henoko to allow the closure of Futenma Air Base, situated smack in the middle of Ginowan City. “It’s the same force.”

“Before, people didn’t think we should close all the bases,” Yamashiro added, sitting in a sweltering tent encampment across from Camp Schwab. “But after this incident, people are afraid, and really angry.”

On weekends, Yamashiro flies to one of Japan’s main islands and delivers speeches anywhere he can — at train stations, or conference halls — discussing what he sees as the onerous U.S. military presence in Okinawa. He has nothing but disdain for Abe, who has fought for the expansion of Camp Schwab and modifications to Japan’s postwar pacifist constitution. “I think Abe wants to start a war with China,” he said.

++

Eisaku Yara, now in his sixth term as a Naha City assemblyman, said it would be dangerous for all U.S. troops to be suddenly booted from Okinawa. Though anti-base forces have found an energetic advocate in the current governor, Takeshi Onaga, Yara believes “not even half” of Okinawans want all Americans gone.

“Personally, I’d be sad if they all left,” said Yara, who thinks a gradual reduction is the most prudent approach. “After 70 years, we are all family here.”

But Yara said more needs to be done to deepen understanding between Americans and Okinawans. Even as a local assemblyman, he said, he has scant substantive contact with U.S. military officials. Some come to the city’s annual holiday party, but there’s little follow-up after business cards are exchanged.

“As a junior high school kid, I remember doing a weekend home stay on one of the U.S. bases. I stayed with a black serviceman, his wife and two kids,” recalled Yara. “It was a chance to experience American culture, which I only knew from TV and movies.”

More such programs are sorely needed, he said. And Okinawans, he added, could do more to introduce Americans to Japanese culture and language.

Eldridge agreed. More needs to be done, he said, to publicize the good things Okinawa-based troops do, both on and off duty — from volunteering to disaster-relief missions after earthquakes, typhoons and tsunamis.

“If you get the community relations right, the politics fall in place,” he said.

Particularly unsettling to many locals are provisions of the Status of Forces Agreement that can shield U.S. service members, civilian employees and some contractors from prosecution in Japan if, for example, they are on duty when an alleged crime is committed, or if they hightail it back to base after breaking the law.

Shinzato’s case shows that base workers, to some extent, are indeed subject to the Japanese justice system. But Ryota Shimabukuro, a reporter who covers the U.S. military for the local newspaper Ryukyu Shimpo, said Okinawans increasingly feel that any exemptions at all may encourage service members to engage in riskier behaviors. “This creates a situation of moral hazard.”

+++

Back on Route 58, the silent memorial organized by Neighborhood Church Okinawa went ahead despite the Siangcos’ trepidation. The response, they said, made them feel all was not lost.

“People, not even church members, stopped their cars, parked and joined us,” said Sylvia Runyon, a 39-year-old photographer who was previously in the military. Local people pulled over to offer water and tea, and some motorists were even moved to tears. “It was overwhelming,” she said.

Pictures of the event went viral. Church members are now trying to think of ways to capitalize on their momentum. They are considering selling stickers with their heart logo and donating the proceeds to the victim’s family.

“There is a need to create a dialogue, to bring unity,” said Christian Siangco. “That is where God is challenging us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.