For an Afghan boy, Muhammad Ali was the ‘man of steel’

- Share via

Reporting from Kabul — Growing up as an Afghan immigrant in California, there were only a few names that were instantly recognizable in my family.

There were the titans of the Cold War-era politics that had managed to turn our country into one of its main events — Gulbuddin Hekmetyar, our prime minister; the U.S. president, Ronald Reagan; Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union.

Then there were the Afghan and Iranian pop stars, whose music filled our house and our car rides to school — Ahmad Zahir and Googoosh. As the ‘80s and ‘90s wore on, it was the groundbreaking music videos of Michael and Janet Jackson and Madonna that first defined Western culture to my siblings and me.

But there was one name that seemed to connect both worlds. A name that sounded like mine but which I first heard in the United States, not Afghanistan.

Muhammad Ali.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

He was the icon that bridged my parents’ experiences in Afghanistan and the new life we all, but especially my siblings and I, would have to build in the United States.

To my parents, he was the Muslim sports icon whose golden age coincided with what they saw as their own nation’s golden age.

Initially, their lives seemed to be in stark contrast with one another — my parents started out as wealthy elites whose ethnicity meant they never had to face racism and prejudice in Afghanistan, while Ali, the grandson of a slave, grew up in Kentucky during the Jim Crow era.

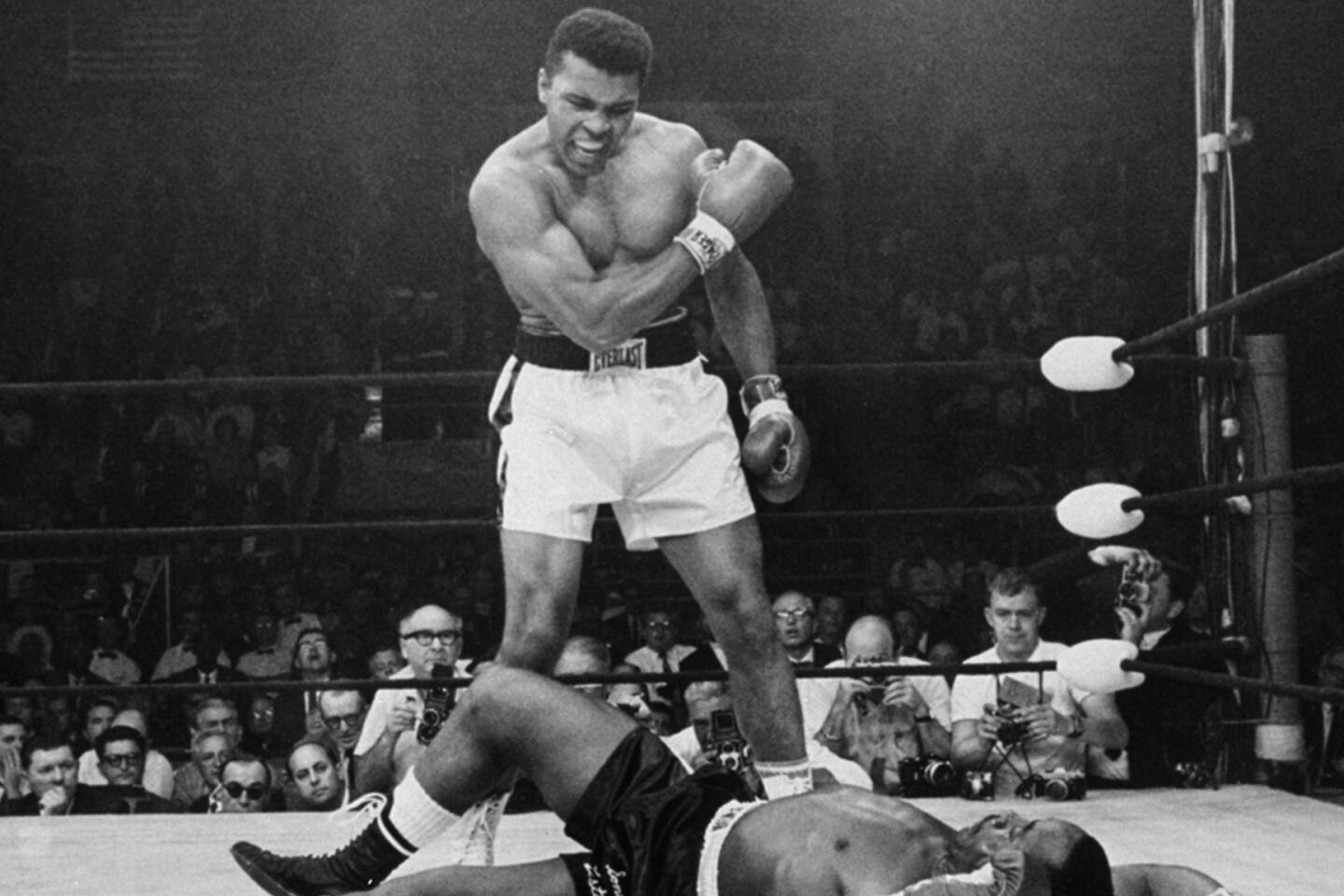

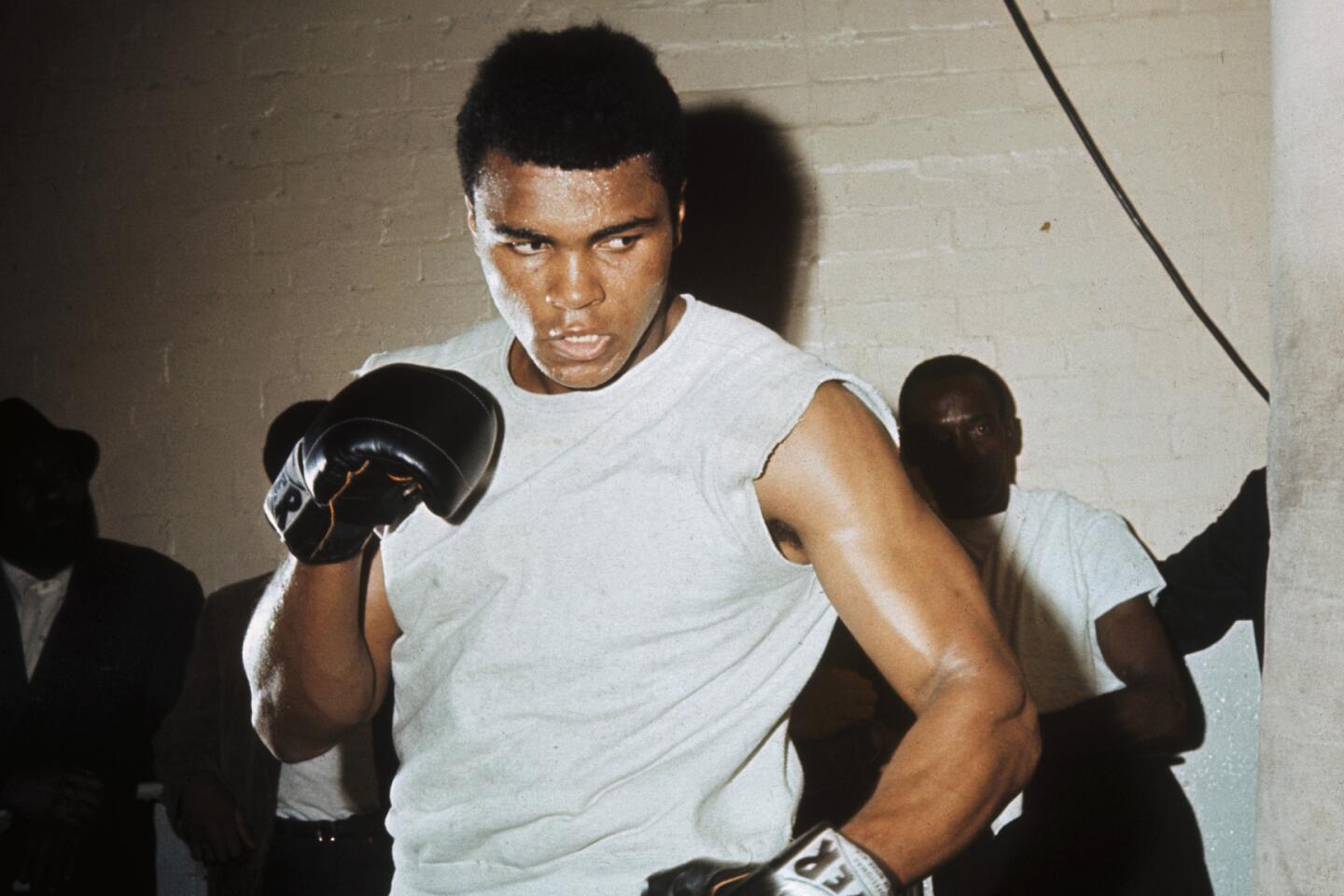

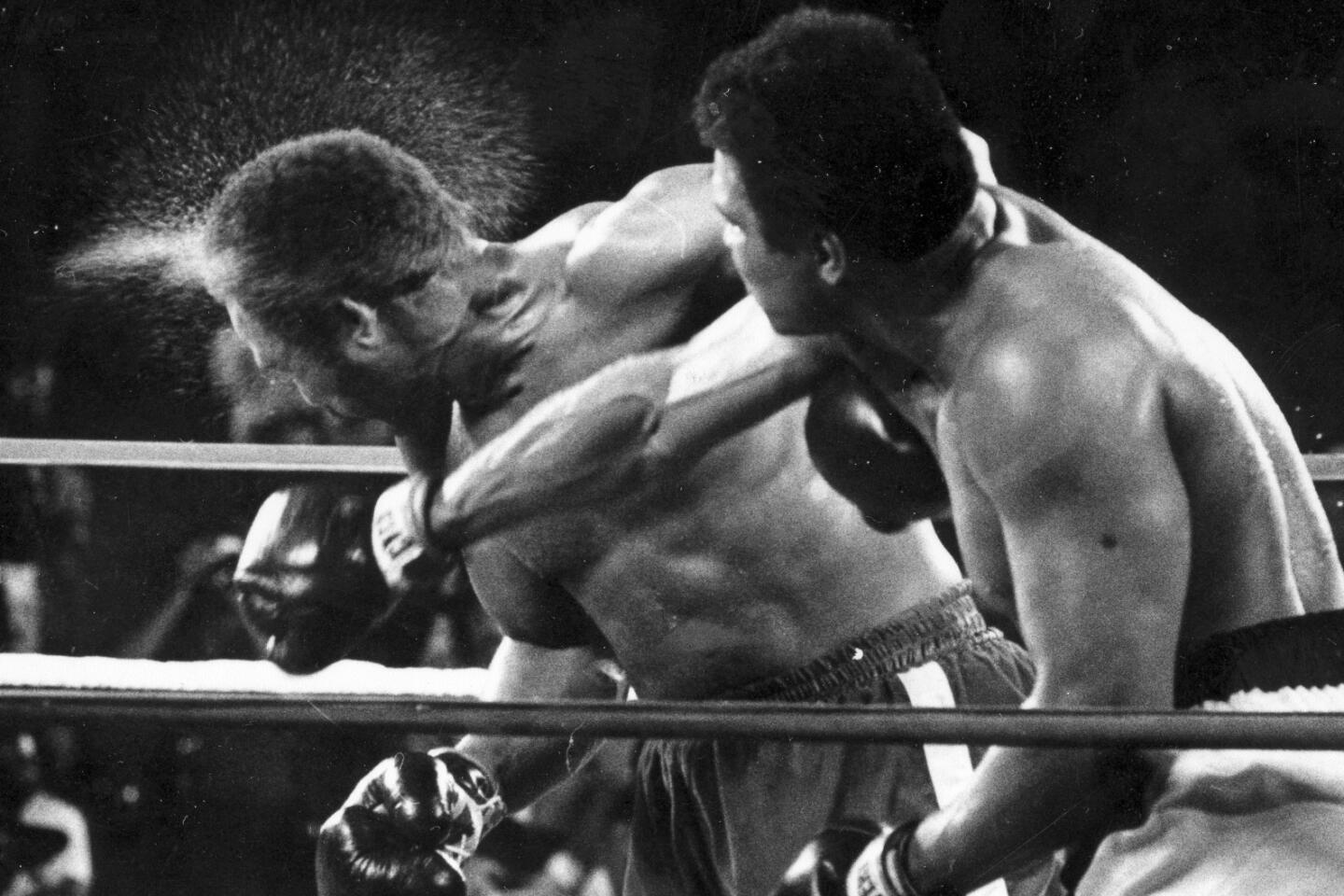

My parents were given nearly every advantage, whereas Ali had to fight, literally and figuratively, for everything he had.

As Ali’s boxing glory began to fade in the early 1980s, my family was forced to flee a Soviet-occupied Afghanistan and eventually settled in the Bay Area, where for the first time, they would face racism and economic hardship as they struggled to build a new.

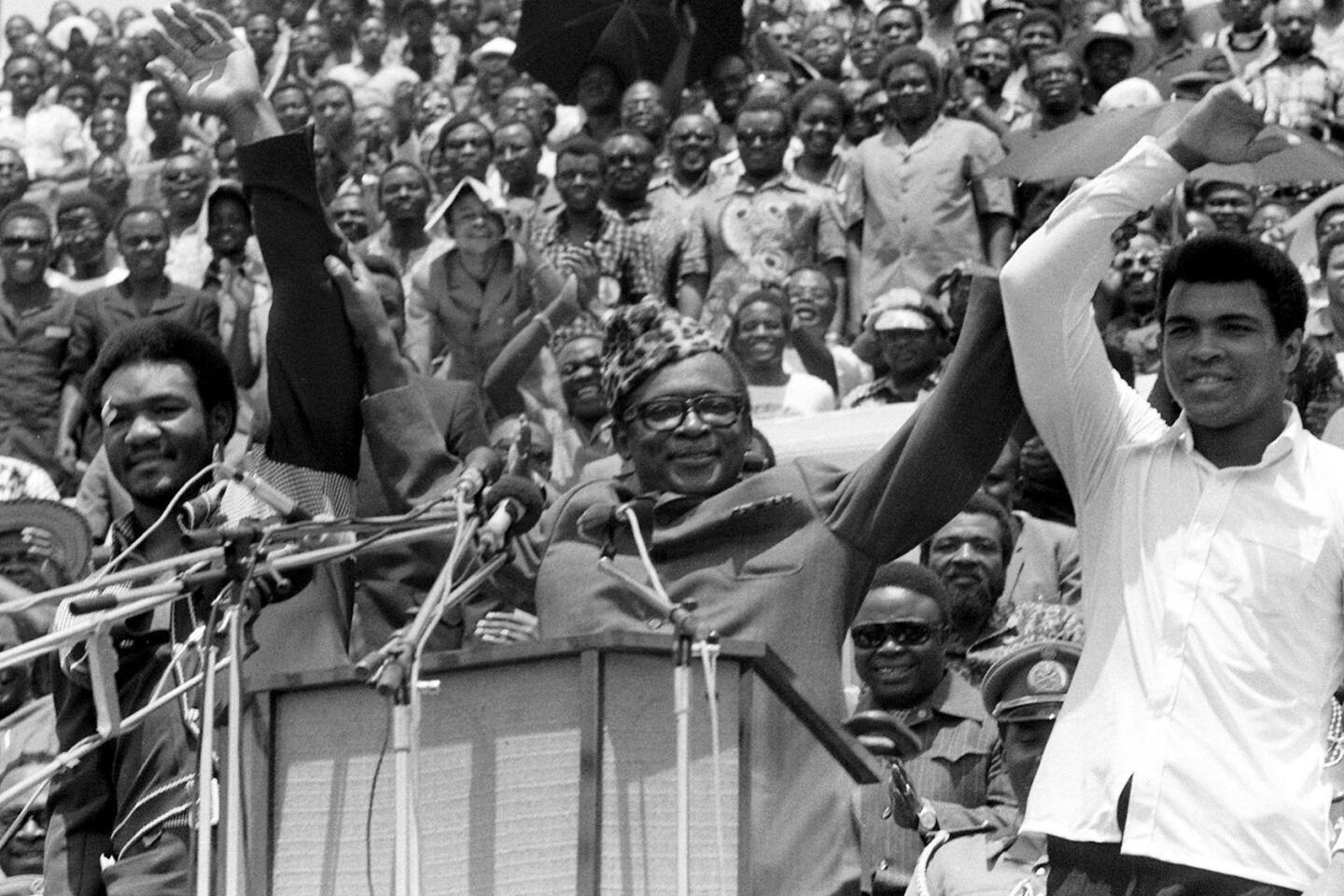

To me, Ali was a Muslim man who made it to international fame. A man who showed us what true global fame meant. As I grew older I understood just what it meant for Ali, a black Muslim, to rise to the heights of fame, first in the United States, and eventually around the world.

But I’m sure I’m not the only one.

Ali was an icon to hundreds of millions of other Muslims in the United States and the post-colonial world.

Even before he was jailed for his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War — citing his religious beliefs as one of the reasons he had “no quarrel with them Viet Cong” — Ali stood by his convictions.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big, powerful America,” he said years before the United States began its incursions into Afghanistan and Iraq.

In 1964, after he declared Cassius Clay, his father’s name, was “a slave name,” Ali did not capitulate to sportscasters who refused to refer to him by his new name, which meant “beloved of God.”

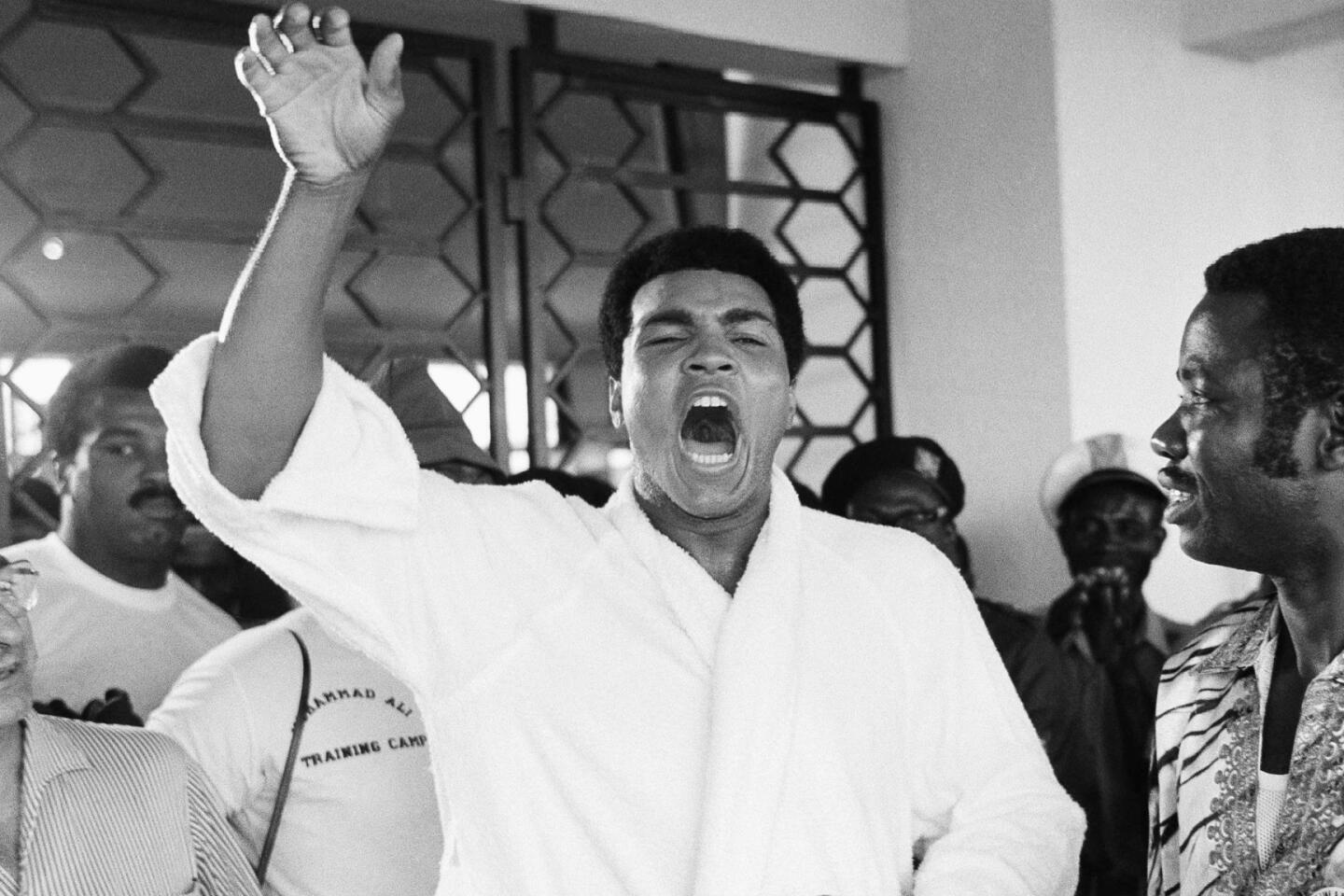

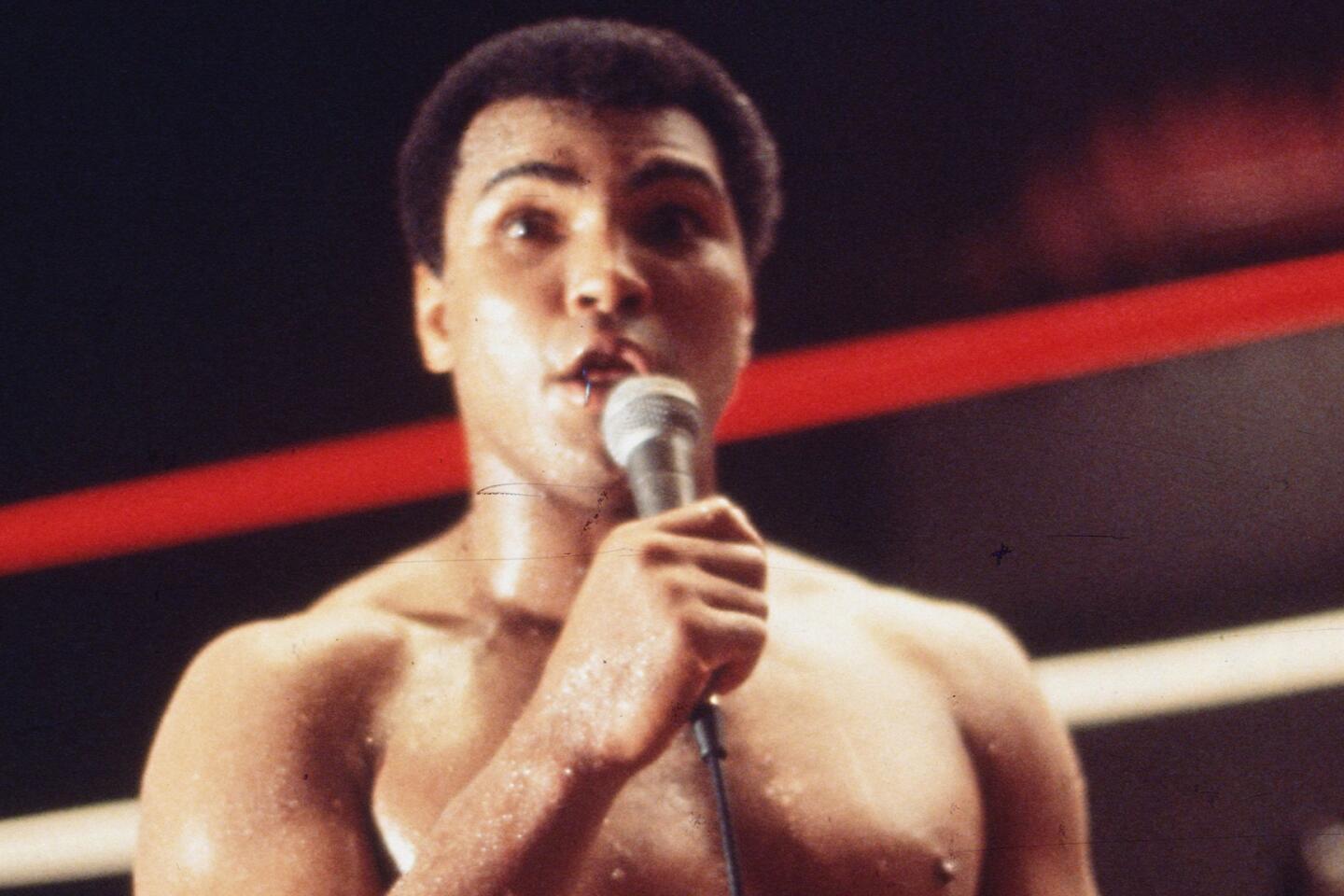

“I insist people use it when people speak to me and of me,” he said with all of the conviction and bravado that initially earned him the moniker the “Louisville Lip.”

He showed the world that he could be a proud American — in spite of his activism against the racism he faced simply for being a black man in the United States — and a proud Muslim.

This was decades before Barack Hussein Obama — a Hawaiian-born child of Hawaiian and Kenyan parents — was plagued with questions about his devotion to the nation due to false suspicions around his religion and place of birth, rooted in Islamophobic reactions to his name.

But Ali didn’t stop there.

In 1971, when British TV journalist Michael Parkinson asked Ali: “Do you have a bodyguard,” his response was simple.

While the studio audience laughed at the question, the heavyweight champ responded: “I have one bodyguard … That’s God. Allah. He’s my bodyguard, he’s your bodyguard,” Ali said only seconds after reciting Koranic scripture live on British television.

One of the most famous men in the world, a black man from the United States, had brought the Koran into millions of British homes at a time when few in the West had heard of Iran, Afghanistan or Iraq.

Before TV pundits devoted countless hours to debating Islam in often-vitriolic tones, Ali forced his millions of fans around the world to confront the image of a successful Muslim head on.

His refusal to go by any other name also helped make it safe for me as a Muslim immigrant with a strange name in the United States.

“Like Muhammad Ali,” people would say.

“Yes, my middle name is Muhammad,” I would respond.

He was the reason my coworkers at the Apple Store in San Francisco would chant: “Ali, Boma Ye!” when I walked into a workplace that could often be rife with barely veiled racial tensions.

Today, in an environment where the presumed Republican nominee for the U.S. presidency, Donald Trump, can call for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” there is a seeming dearth of universally accepted Muslim figures we can point to as an embodiment of a real Muslim, not the feared boogeyman espoused by Western media.

Yes, there are intellectuals and politicians like Reza Aslan, Arsalan Iftikhar and Keith Ellison, but none reached the globe-spanning universal fame of Ali.

Of course, Ali did take on Trump.

“I am a Muslim and there is nothing Islamic about killing innocent people in Paris, San Bernardino, or anywhere else in the world. True Muslims know that the ruthless violence of so called Islamic jihadists goes against the very tenets of our religion,” he said in response to Trump last year.

He did not “condemn” the attacks carried out by a small group as so many Muslims are expected to by a deeply Islamophobic global society. Instead, he told the world, and Trump, to see the vast majority of the world’s more than 1 billion Muslims as they see him.

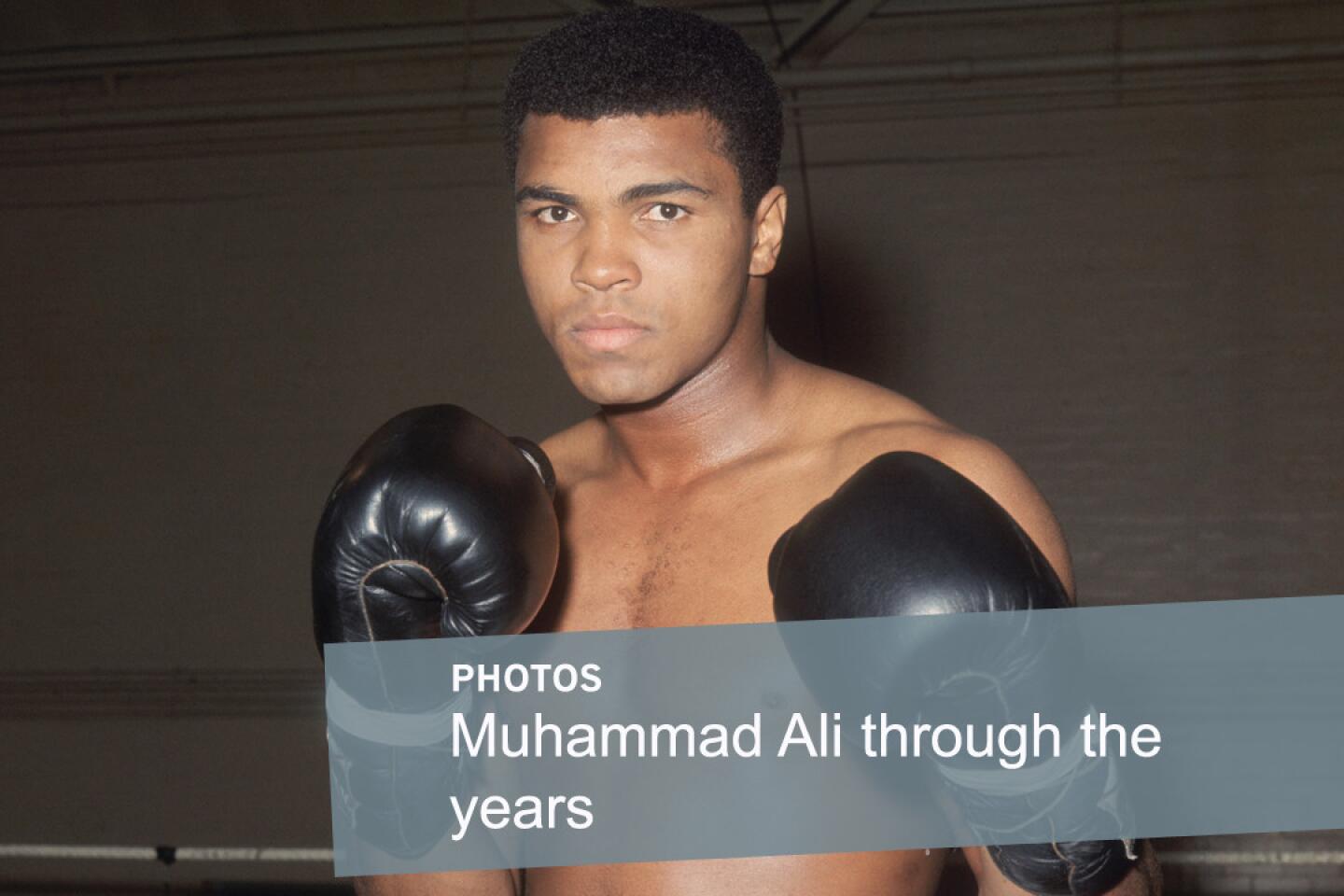

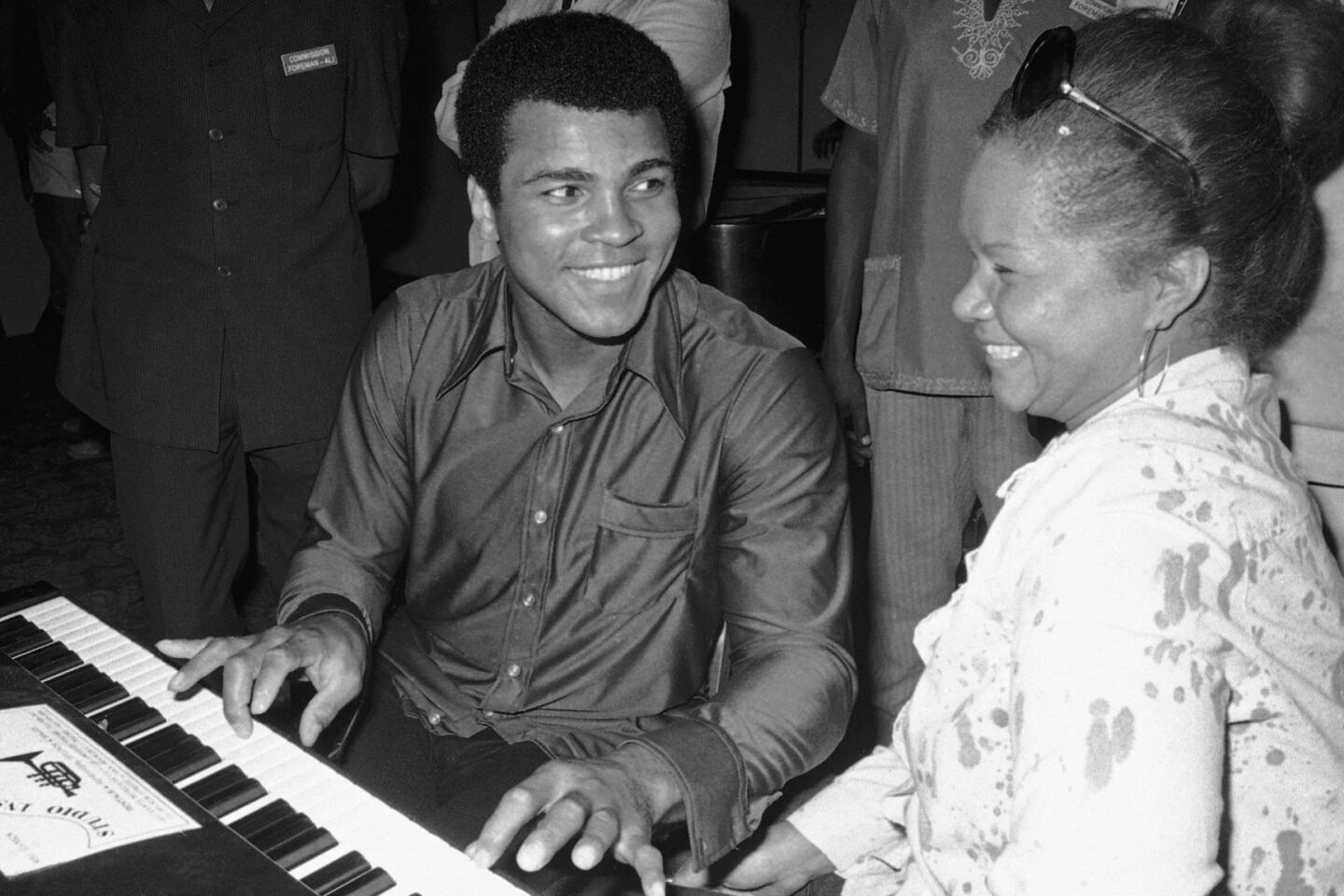

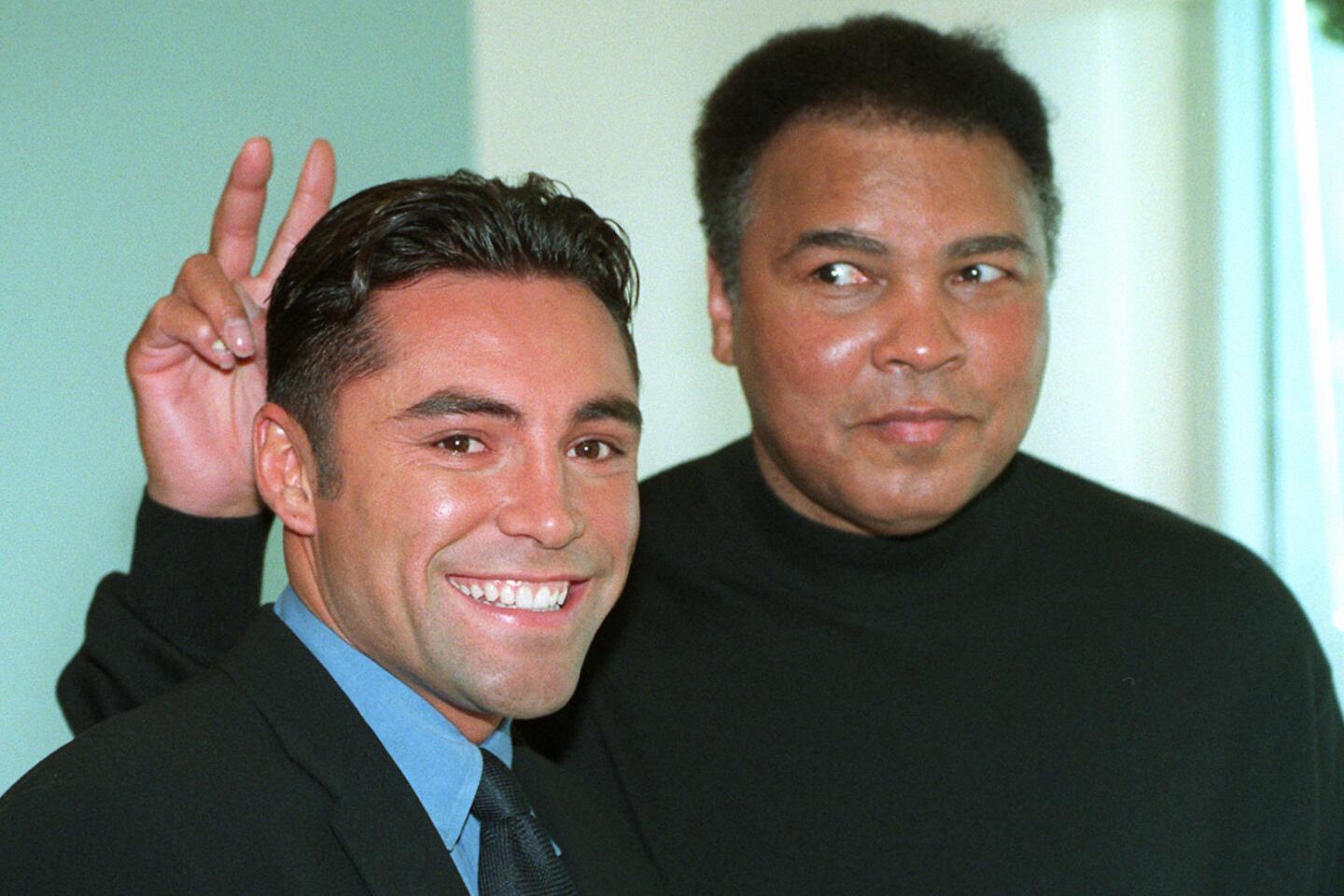

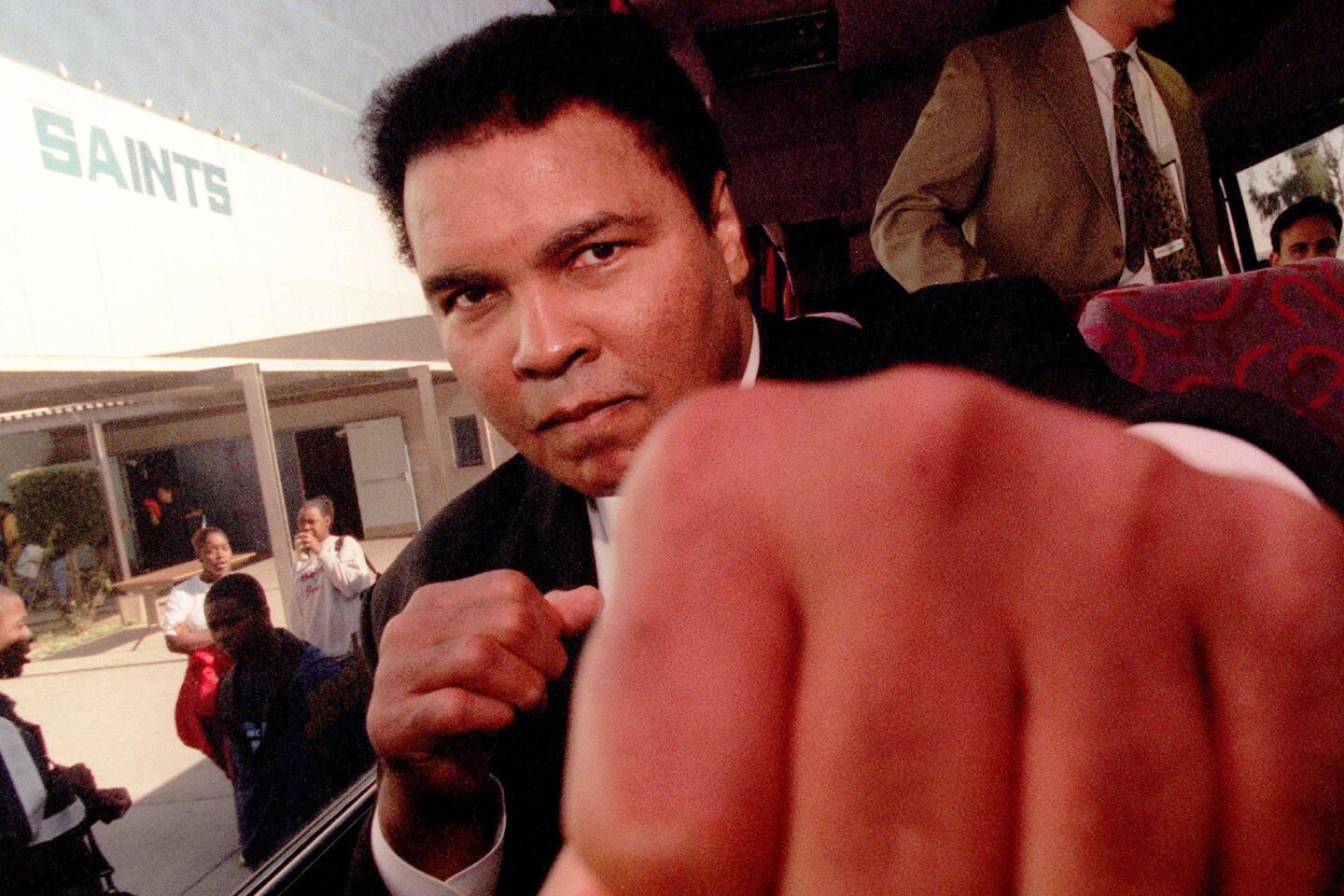

Throughout his 74 years of life, Ali managed to be many things to many people — a championship boxer, a showman, a black man and a Muslim.

I discovered Ali as an Afghan immigrant to a strange country and now, because of his accomplishments and his bravery, I write about him as a journalist for the United States’ fourth-largest newspaper after having returned to my country of birth.

For this, Ali, the man who has a name like mine, will always be my Muslim superhero — my man of steel.

Latifi is a special correspondent

MORE

Ali once talked a man out of jumping off a building in Los Angeles

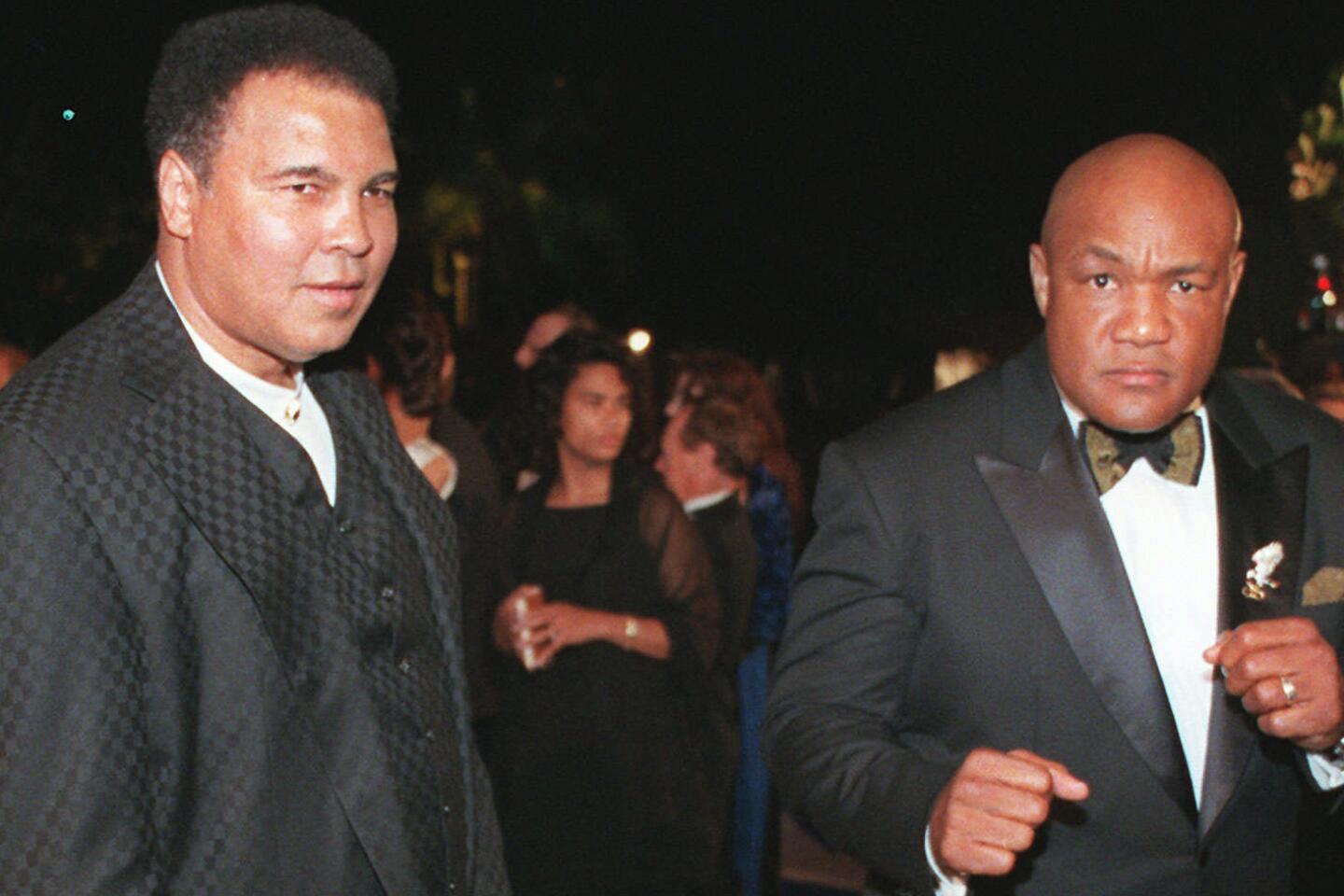

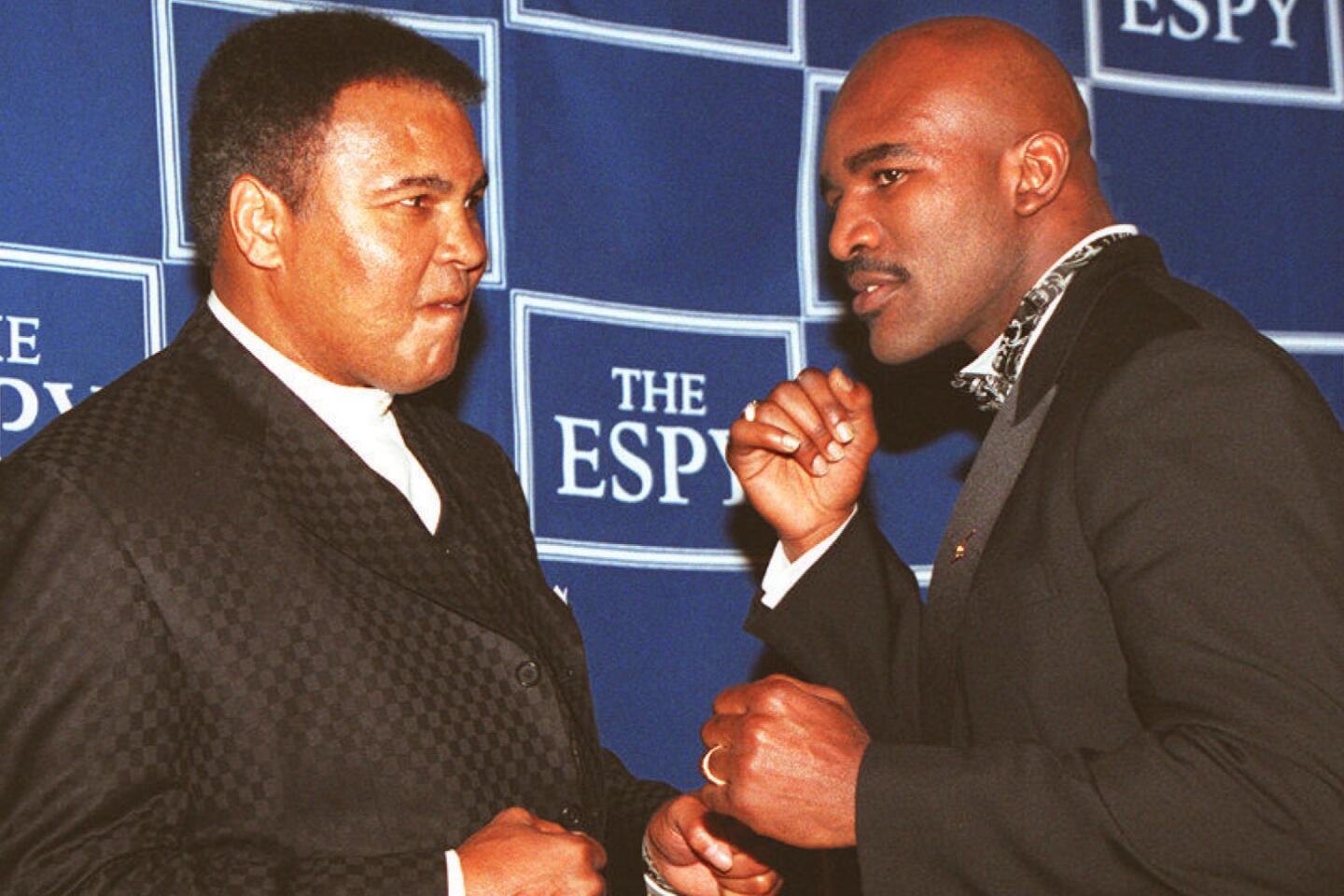

Muhammad Ali’s peers react to the passing of a legend

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.