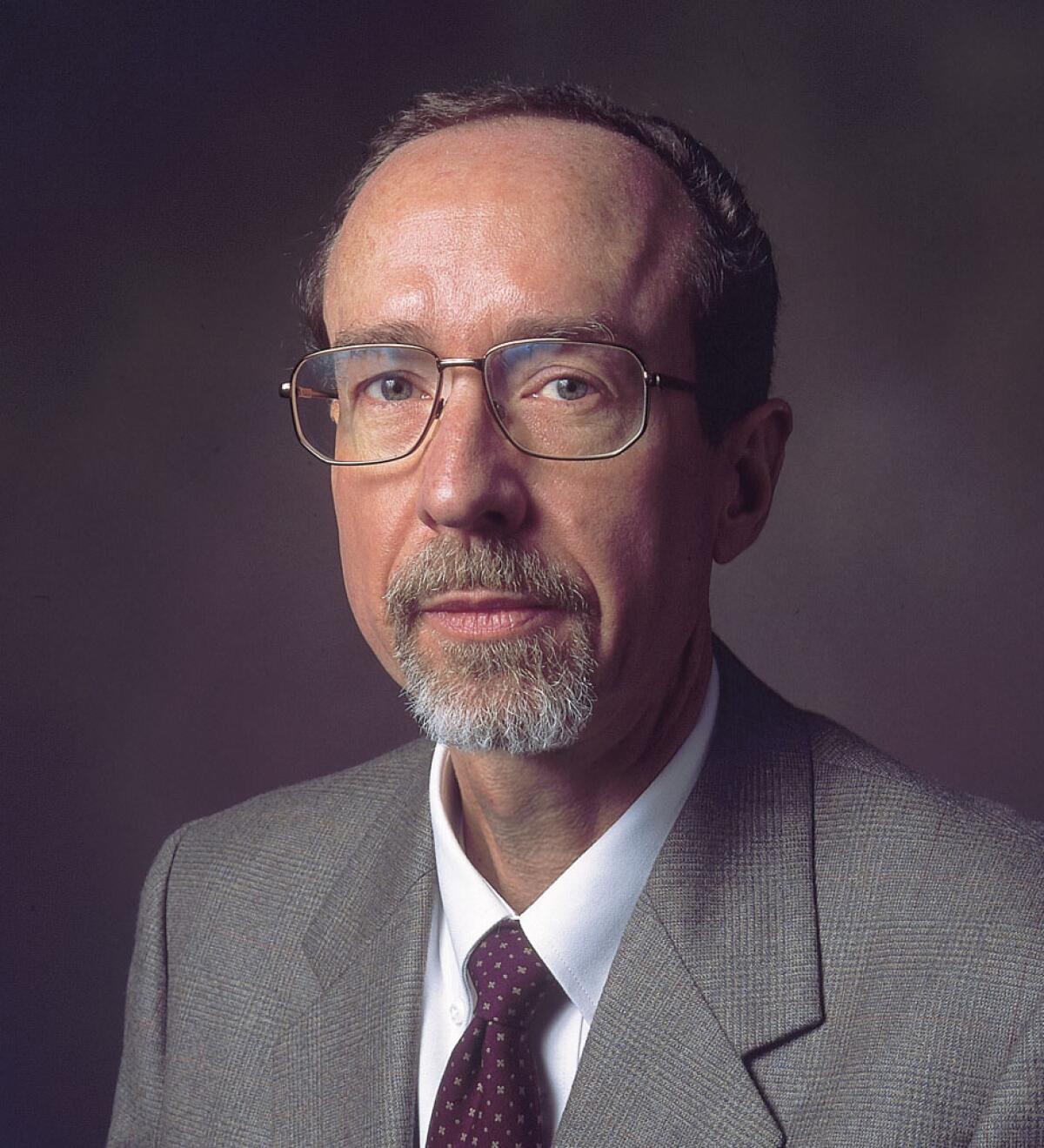

Foreign correspondent David Holley, who covered pro-democracy protests, dies at 74

- Share via

TAIPEI, Taiwan — In the early hours of June 4, 1989, Chinese soldiers — under orders from the country’s leader, Deng Xiaoping, to clear pro-democracy protesters from Beijing’s Tiananmen Square — opened fire, killing hundreds.

Times journalist David Holley watched from the window of a nearby hotel, using a phone in a coffee shop to report what he saw to colleagues in the Beijing bureau as gunfire crackled in the background.

Three decades later, in an article reflecting on what he saw and why it remains one of the most pivotal moments in China’s modern history, he wrote: “This Beijing massacre ultimately strengthened Deng’s control and froze into place his formula for China’s modernization: one-party dictatorship paired with market-oriented reforms. ... Over the last 30 years, China has grown stronger and more prosperous, but the formula remains unchanged.”

For the record:

5:35 p.m. Aug. 23, 2024A previous version of this article said Holley died at home in Nagano at 73. He died at a hospital in Tokyo and was 74.

Holley spent two decades as a Times foreign correspondent, covering pro-democracy street protests in nearly a dozen other countries before going into teaching. He died Aug. 4 in a Tokyo hospital at age 74. His cousin Frederick Holley said the cause was complications from a chronic health condition.

Former colleagues remembered Holley for his gentle personality and dedication to his reporting.

In the predawn hours of June 4, 1989, the Chinese army was bringing a bloody end to seven weeks of student-led protests centered on Tiananmen Square, Beijing’s historic center.

“Everyone will say he was kindhearted and generous and supportive, a person of integrity, a hard worker,” said Simon Li, a former editor at The Times who worked with Holley on the foreign desk.

Li added that Holley’s fluency in Chinese and Japanese enhanced his work: “David’s language facility was an advantage that adorned his coverage. He added a dimension to reporting from those two countries that perhaps we hadn’t had before.”

Holley grew up in Rochester, N.Y., the youngest of three siblings. An Asian studies class during his senior year in high school piqued his interest in East Asian languages. After obtaining a bachelor’s degree in Chinese from Oberlin College, he traveled around the world studying languages and working odd jobs, including at an ice cream parlor.

He met his wife, Fumiyo Asahi, while learning Spanish in Mexico. They were married in Japan, where he taught English for a few years.

Holley went on to earn a master’s degree in communications at Stanford University with the goal of becoming a foreign correspondent. After graduation, he worked for The Times in Southern California for seven years for before moving to Beijing in 1987.

“I wanted to go to all of the places where the most people lived,” Holley told one of his former students, Jin Young Lim, in a 2021 podcast. “I was very consciously trying to educate myself about the places that had a lot of people, with the idea that over the course of my lifetime, the places with a lot of people were going to become very, very important geopolitically, internationally, for American foreign relations.”

A growing number of Americans consider China an enemy whose influence should be contained, a Pew Research study finds

After Beijing, Holley served as a Times correspondent in Tokyo, Warsaw and Moscow before leaving the newspaper in 2007 to teach journalism, history and American politics at Waseda University and Keio University in Japan.

Lim, who graduated from Waseda University in 2018, said Holley has been the most influential person in his life.

After retirement three years ago, Holley took up farming in the Nagano countryside but kept in frequent communication via Zoom calls with his former students, his cousin Frederick said.

In the podcast, Holley said that as the relationship between the U.S. and China has turned adversarial, understanding the thinking of Chinese leaders and people is critical for American interests.

With growing mistrust between the the U.S. and China, an election between President Biden and Donald Trump looks like a lose-lose scenario for China.

“For the United States to come out ahead in a competition with China, it’s extremely important to understand why does China act the way it does,” he said. “If American foreign policy can be based on, ‘OK, we are going to work for what’s best for America, but we’re going to be smart about it, we are going to understand our rivals,’ that’s a big step towards making conflict less dangerous, and it’s also a big step to stop thinking of them as rivals, and starting to think of them as also us.”

Despite the world’s huge challenges, Holley said, he maintained a sense of optimism.

“Whatever the tensions may be between Washington, Beijing and Moscow, at least the leaders of these three great powers get together regularly at global summits where everybody is reasonably cordial to each other,” he said in a TEDx talk in 2014.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.