Aid worker’s airport disappearance stokes fear of repression after disputed Venezuela vote

- Share via

CARACAS, Venezuela — It’s been a week since anybody’s heard from Edni López. The 33-year-old political science professor and award-winning poet was preparing to board a flight to Argentina to visit a friend when she texted from the airport that something was wrong with her passport.

“Migration took my passport because it’s showing up as expired,” she wrote her boyfriend in the message shared with the Associated Press. “I pray to God I don’t get screwed because of a system error.”

What happened next remains a mystery — one contributing to the climate of fear and repression that has engulfed Venezuela after its disputed presidential election, the most serious wave of human rights abuses since Latin America’s military dictatorships in the 1970s.

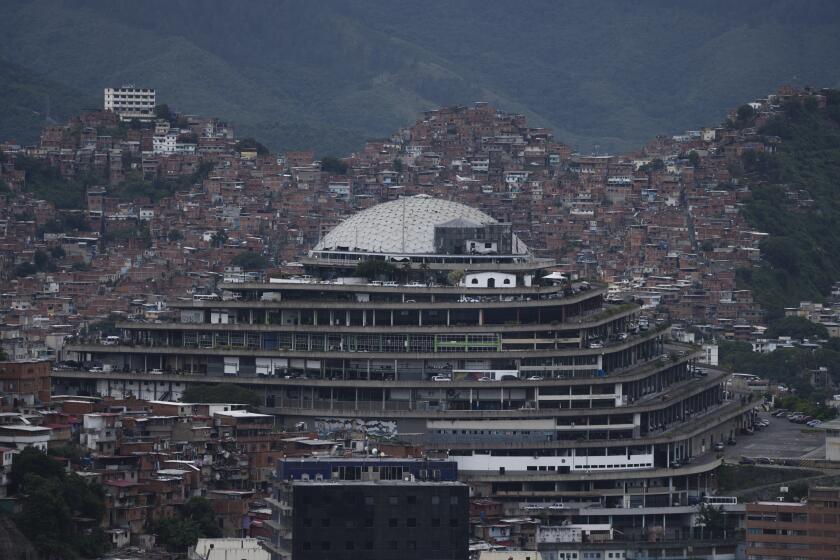

When López’s mother, Ninoska Barrios, and her friends learned she didn’t board the Aug. 4 flight, they started frantically combing detention centers. Finally, on Tuesday — more than 48 hours later — they learned she was being held, incommunicado, by Venezuela’s feared military intelligence police on unknown criminal charges, unable to see an attorney or speak with her family.

Opposition leaders said they obtained more than 84% of the vote tallies, which show opposition candidate Edmundo González won the election.

“Please, give back my daughter,” a sobbing Barrios pleaded Tuesday outside Venezuela’s top human rights office in a video that went viral on social media. “It’s not right that a Venezuelan mother has to go through all this.”

López’s arrest isn’t unique. Since the July 28 presidential election, security forces have rounded up more than 2,000 people for demonstrating against President Nicolás Maduro or casting doubt on his claim he won a third term despite strong evidence he lost the vote by a more than 2-to-1 margin. Twenty-four people have been killed, according to local human rights group Provea.

The detentions — urged on by Maduro — put Venezuela on pace to easily surpass the number of people jailed during three previous crackdowns against Maduro’s opponents.

Venezuela prosecutor opens criminal probe of opposition leaders González and Machado after they call on armed forces to ditch Maduro amid election crisis.

Those arrested include journalists, political leaders, campaign staffers and an attorney defending protesters. Others have had their Venezuelan passports annulled trying to leave the country. One local activist livestreamed her arrest by military intelligence officers as they broke into her home with a crowbar.

“You’re entering my home arbitrarily, without any search warrant,” Maria Oropeza, an opposition campaign leader in rural Portuguesa state, said in the livestream that abruptly ended after three minutes. “I’m not a delinquent. I’m just an average citizen who wants a different country.”

The repression, much of it seemingly random, is having a chilling effect, said Phil Gunson, a Caracas-based analyst for the International Crisis Group.

The Biden administration recognized Venezuelan opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia as presidential election winner, discrediting Nicolás Maduro’s claims.

“It’s not just discouraging protests. People are scared to go on the streets, period,” said Gunson, adding that parents of teenage boys are especially worried. “There’s a sense that police have a quota to fill and anyone can be stopped and carted away as a suspected subversive.”

The threats start at the top.

“They’re hiding rats, but we’re going to grab them,” ruling socialist party boss Diosdado Cabello said about several prominent opponents in an address to the Maduro-controlled legislature a day after the election.

Meanwhile, Maduro has called on Venezuelans to denounce election doubters via a government-run app originally created to report power outages and complaints about state-provided services.

He also ordered the nation’s telecommunications agency to block access to the social media site X, an attempt to suppress information sharing among people voicing doubts about his claim to victory.

Maduro said the government was refurbishing two gang-dominated prisons to accommodate an expected surge of jailed guarimberos — his dismissive term for middle-class protesters who barricaded themselves in the streets for weeks in 2014 and 2017. “There will be no mercy,” Maduro said on state TV.

But complicating efforts to crush dissent is the changing face of the government’s opponents.

Though demonstrations have been far smaller and tamer than during past bouts of unrest, they’re now more spontaneous, often leaderless and made up of youths — some barely teenagers — from Caracas’ hillside slums who have traditionally been a rock-solid base of support for the government.

“I don’t care how many people have to die,” Cleiver Acuna, a 21-year-old tattoo artist, said at one recent grassroots march in which protesters climbed up lampposts to tear down Maduro campaign posters. “What I want is my freedom. My homeland. I want to live in the Venezuela my grandparents once told me about.”

Maria Corina Machado, the opposition powerhouse who rallied Venezuelans behind a last-minute stand-in candidate after she was barred from running against Maduro, has urged restraint, reflecting the fear many feel.

“There are times to go out, times to meet, and demonstrate all our strength and determination and embrace each other, just as there are times to prepare, to organize, to communicate and to consult with our allies around the world, which are many,” she said in a recorded message posted online Tuesday.

“An operational pause is sometimes necessary.”

But the swiftness of the government’s clampdown does seem to be working. In just 10 days, security forces had rounded up nearly the same number of people as they did over five months in 2017, according to Provea.

“Operation Knock-Knock is a prime tool of state terrorism,” said Oscar Murillo, the head of Provea, referring to surprise, middle-of-the-night detentions.

In the low-income Caracas neighborhood of Catia, once a ruling party stronghold, no one talks politics these days. One woman closed her business and ran home when protests began nearby. Videos of the demonstration flooded her phone over the next several hours, but she deleted them for fear the government was tracking social media posts to identify critics.

“I could get arrested just for having them,” she said.

The sudden silence is a sharp break from the hopeful mood as emboldened opposition supporters confronted security forces who attempted to block anti-Maduro rallies. They served food, lent vehicles to opposition leaders and opened their businesses to them despite knowing they would suffer retaliation from the police or have their businesses shut down.

Even before the current unrest, Venezuela’s human rights record was under intense scrutiny. Maduro is the target of an investigation by the International Criminal Court over allegations of crimes against humanity committed previously.

The government of Venezuela has rejected a report by independent experts working with the United Nations’ top human rights body.

Maduro’s tactics have been likened to those in Central and South America in the 1970s when military dictatorships rounded up opponents and sometimes innocent bystanders. Many were killed, and in Argentina, some were even drugged and dropped from airplanes into the ocean, with no trace of ever having been detained.

Maduro’s alleged abuses may be different from those “dirty war” campaigns by state security forces. But the goal of instilling fear is the same, said Santiago Canton, an Argentine lawyer and secretary general of the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists, a watchdog group.

Canton said López’s case reminded him of the 1977 disappearance in Argentina of a female activist pulled off a plane bound for Venezuela and never seen again. At the time, oil-rich Venezuela was the wealthiest country in South America and a democratic refuge for exiles fleeing military governments across the region.

“What happened 50 years ago is unlikely to occur again,” said Canton, who previously led the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. “But social media is a multiplier factor that didn’t exist before so you can be more selective with the use of force and achieve the same results.”

Machado tried Thursday to push other nations to help end the oppression. “I feel that there has been a lack of firmness from all governments, from all sectors, to demand an immediate end to the madness that is happening,” she told reporters.

Meanwhile, López’s friends and family are at a loss to explain why she was targeted.

Since 2020, she’s been carrying out relief work in poor communities, for which she was honored as one of Venezuela’s “100 Protagonist Women” by the Netherlands’ embassy in Caracas. The work is strictly humanitarian, and López doesn’t belong to any political movement. Her social media profile is void of any anti-government content, consisting mainly of whimsical drawings of butterflies, poems she penned and pictures of beaches and sand dunes from her travels across Venezuela.

Cristina Ramirez, who moved to Argentina from Caracas eight years ago, joining more than 7.7 million Venezuelans who’ve fled the country, said she bought a ticket for López in May so her friend could enjoy a much-deserved vacation.

The two were looking forward to catching up after a long separation and a difficult year for López, whose family is struggling financially. Ramirez worries that her friend, who takes medicine for diabetes, is suffering in prison without knowing what led to the nightmare.

“It was going to be her first trip outside Venezuela,” Ramirez said in a phone interview. “I’m still waiting for her.”

Garcia Cano and Goodman write for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.