House passes reauthorization of U.S. surveillance program after days of upheaval over changes

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The House passed a bill Friday to reauthorize and provide sweeping reforms of a key U.S. government surveillance tool, without including broad restrictions on how the FBI uses this crucial program to search for Americans’ data.

The bill, approved 273 to 147, now goes to the Senate, where its future is uncertain. The program is set to expire Friday unless Congress acts.

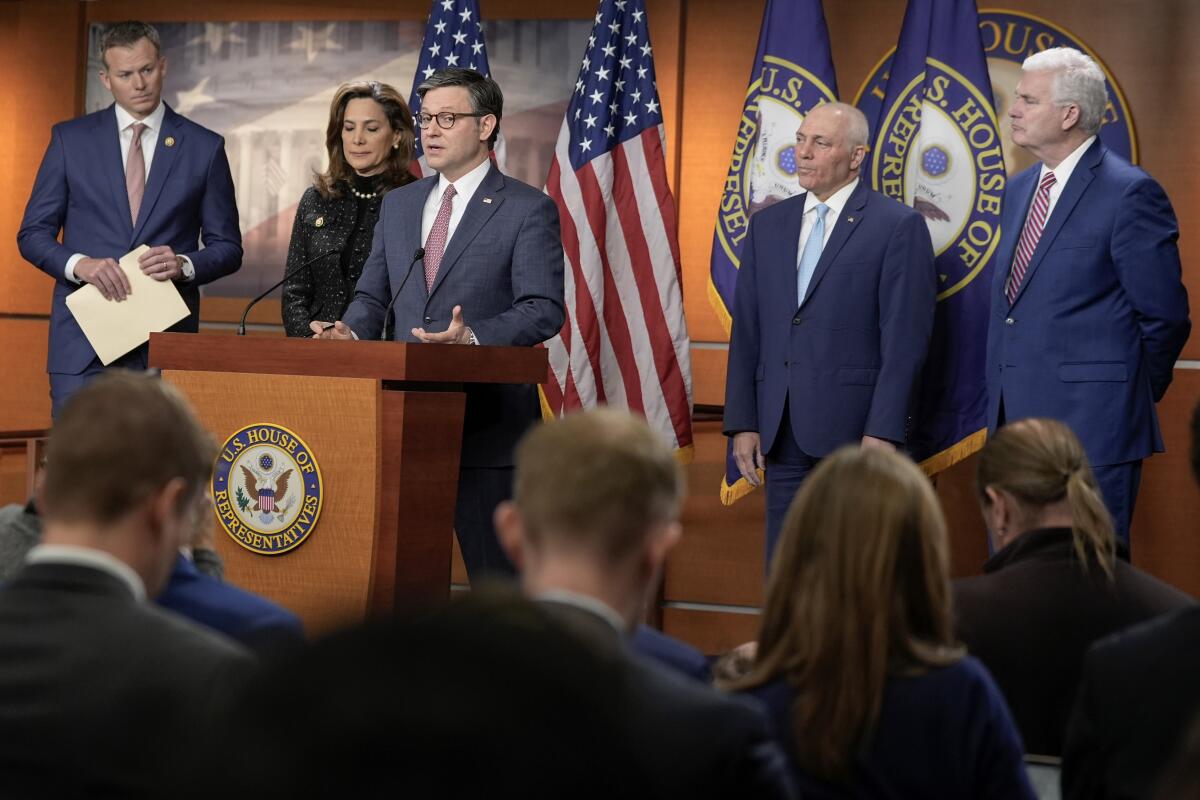

House Speaker Mike Johnson brought forward the revised proposal, which would reform and extend Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act for two years, instead of the five-year reauthorization that was first proposed.

Johnson (R-La.) hoped that the shorter timeline would sway GOP critics by pushing any future debate on the issue to the presidency of Donald Trump if he were to win back the White House in November.

A separate provision, ending warrantless surveillance of Americans, was also offered on the floor Friday but failed to get a majority of the votes required to pass the House, despite gaining support from strange bedfellows from the far right and far left.

Skepticism of the government’s spying powers has grown dramatically in recent years, particularly among those on the right.

Republicans have clashed for months over what a legislative overhaul of the FISA surveillance program should look like, creating divisions that spilled onto the House floor this week as 19 broke with their party to prevent the bill from coming up for a vote.

However, the revised proposal, with the shortened timeline, helped flip some conservative opposition to the legislation.

Could Ukraine lose the war? Once nearly taboo, the question hovers in Kyiv, but Ukrainians believe they must fight for their lives against Putin’s troops.

“The two-year time frame is a much better landing spot, because it gives us two years to see if any of this works rather than kicking it out five years,” Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas) said Thursday. “They say these reforms are going to work. Well, I guess we’ll find out.”

The legislation would permit the U.S. government to collect, without a warrant, the communications of non-Americans located outside the country in order to gather foreign intelligence. The reauthorization is currently tied to a series of reforms aimed at satisfying critics who complained of civil liberties violations against Americans.

But far-right opponents have complained that those changes did not go far enough.

The vocal detractors are some of Johnson’s intraparty critics, members of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus, who have railed against the speaker for several months for reaching across the aisle to carry out the basic functions of the government.

To appease some of those critics, Johnson plans to bring forward next week a separate proposal that would close a loophole that allows U.S. officials to collect data on Americans from Big Tech companies without a warrant.

“All of that added up to something that I think gave a greater deal of comfort,” Roy said.

Though the program is technically set to expire Friday, the Biden administration has said it expects its authority to collect intelligence to remain operational for at least a year, thanks to an opinion this month from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which receives surveillance applications. But officials say that court approval shouldn’t be a substitute for congressional authorization, especially since communications companies could cease cooperation with the government.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

First authorized in 2008, the spy tool has been renewed several times, as U.S. officials see it as crucial in disrupting terrorist attacks, cyber intrusions and foreign espionage. It has also produced intelligence that the U.S. has relied on for specific operations.

But the administration’s efforts to secure reauthorization of the program have repeatedly encountered fierce, bipartisan opposition. Democrats such as Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon who have long championed civil liberties have aligned with Republican supporters of Trump.

In a post Wednesday on his social media site, Trump stated incorrectly that Section 702 had been used to spy on his presidential campaign. A former advisor to Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was targeted for surveillance over potential ties to Russia under a different section of the law.

A specific area of concern for lawmakers is the FBI’s use of the vast intelligence repository to search for information about Americans and others in the United States. Though the surveillance program targets only non-Americans who are in other countries, it collects communications of Americans when they are in contact with those targeted foreigners.

In the last year, U.S. officials have revealed a series of abuses and mistakes by FBI analysts in improperly querying the intelligence repository for information about Americans or others in the U.S., including about a member of Congress and participants in the racial justice protests of 2020 and the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol.

Those violations have led to demands for the FBI to have a warrant before conducting database queries on Americans. FBI Director Christopher A. Wray has warned that this would gut the program’s effectiveness and would be legally unnecessary, given that the information in the database has been lawfully collected.

“While it is imperative that we ensure this critical authority of 702 does not lapse, we also must not undercut the effectiveness of this essential tool with a warrant requirement or some similar restriction, paralyzing our ability to tackle fast-moving threats,” Wray said in a speech Tuesday.

Amiri and Tucker write for the Associated Press. AP writer Kevin Freking contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.