New Iowa law gives state authority to arrest and deport migrants

- Share via

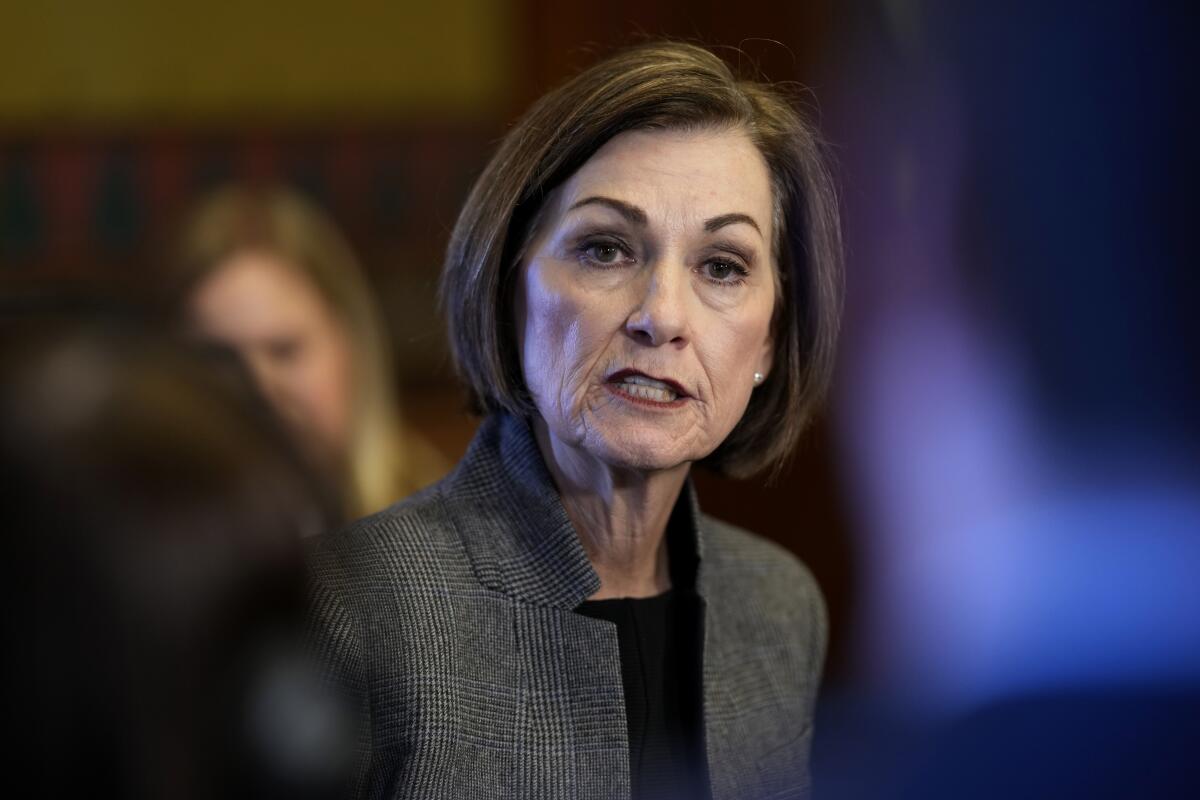

DES MOINES — A bill signed into law by Gov. Kim Reynolds this week makes it a state crime for a person to be in Iowa if previously denied admission to or removed from the United States.

The law, which takes effect July 1, has elevated anxiety in Iowa’s immigrant communities and has prompted questions among legal experts and law enforcement on how it will be enforced. It mirrors part of a Texas law that is currently blocked in court.

The move comes amid national fights between Republican states and Democratic President Biden over who should enforce the law at the U.S.-Mexico border and how to do it.

Louisiana this week also joined the growing list of legislatures seeking to expand states’ authority over border enforcement. Its GOP-led Senate advanced a bill that would empower state and local law enforcement to arrest and jail people in the state who entered the U.S. illegally, similar to the measures in Iowa and Texas.

In Louisiana, bills and policies targeting migrants suspected of entering the country illegally have been pushed to the forefront over the last four months under new conservative leadership. One bill looks to ban “sanctuary city” policies that allow local law enforcement to refuse to cooperate with federal immigration officials unless ordered by a court. Another would set up funding to send Louisiana National Guard members to the U.S.-Mexico border in Texas.

In Iowa, Reynolds accused Biden of not enforcing immigration laws and putting the “safety of Iowans at risk.”

Texas’ controversial immigration law is on hold again after court moves that confounded the Biden administration and spurred outrage from Mexico’s government.

Opponents argue such measures are unconstitutional, will not do anything to make the state safer, and will only fuel negative and false rhetoric directed toward migrants.

After the Iowa Legislature passed the bill, Des Moines Police Chief Dana Wingert told the Associated Press in an email in March that immigration status does not factor into the department’s work to keep the community safe. He said the force is “not equipped, funded or staffed” to take on responsibilities that are the federal government’s.

“Simply stated, not only do we not have the resources to assume this additional task, we don’t even have the ability to perform this function,” Wingert said.

Shawn Ireland, president of the Iowa State Sheriffs’ and Deputies’ Assn. and a deputy sheriff in Linn County, also said in a March email that law enforcement officials would have to consult with county attorneys for guidance on implementation and enforcement.

A bill in Iowa that would allow the state to arrest and deport some migrants is stoking anxiety among immigrant communities.

The Iowa legislation, like the Texas law, could mean criminal charges for people with outstanding deportation orders or who have previously been removed from or denied admission to the U.S. Once in custody, migrants could either agree to a judge’s order to leave the U.S. or be prosecuted.

The judge’s order must identify the transportation method for leaving the U.S. and a law enforcement officer or Iowa agency to monitor migrants’ departures. Those who don’t leave could face rearrest under more serious charges.

The Texas law is stalled in court after a challenge from the U.S. Department of Justice that says it conflicts with the federal government’s immigration authority.

The bill in Iowa faces the same questions of implementation and enforcement as the Texas law, since deportation is a “complicated, expensive and often dangerous” federal process, said immigration law expert Huyen Pham of Texas A&M School of Law.

In the meantime, Iowa’s immigrant community groups are organizing informational meetings and materials to try to answer people’s questions. They’re also asking local and county law enforcement agencies for official statements, as well as face-to-face meetings.

At one community meeting in Des Moines, 80 people gathered and asked questions in Spanish, including: “Should I leave Iowa?”

Others asked: “Is it safe to call the police?” “Can Iowa police ask me about my immigration status?” And: “What happens if I’m racially profiled?”

Fingerhut writes for the Associated Press. A Times staff writer and AP writer Sarah Cline in Baton Rouge, La., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.