- Share via

MYROLYUBIVKA, Ukraine — Sometimes, he visits her in dreams. In her waking hours — treading a muddy village byway, casting an eye across a desolate field — hope pulses in her like a beating heart: that she might somehow find him.

As Europe’s largest land war since World War II enters its third year on Saturday, Ukraine is full of wounded souls like Olena Kovalyk, caught in the quest for some trace of a lost loved one.

There are tens of thousands of these vanished: soldiers who disappeared into the maw of battle, children spirited away for adoption in Russia, civilian villagers like Olena’s husband, Oleh, her childhood sweetheart, who engaged in quixotic acts of defiance against a powerful occupying army.

For those left behind, grief and uncertainty swirl together, muddy rivulets in a vast tributary. The amorphous sense of loss echoes a larger national sense of pervasive not-knowingness: No one can say when, or how, this war might end.

But some, like Olena, have convinced themselves they will find a measure of comfort in confirming beyond any doubt that the worst has indeed come to pass.

To that end, she believes in patience. She believes in paying close attention. Perhaps the answer will come in her dreams.

“I know,” she said, “that eventually, he’ll tell me where he is.”

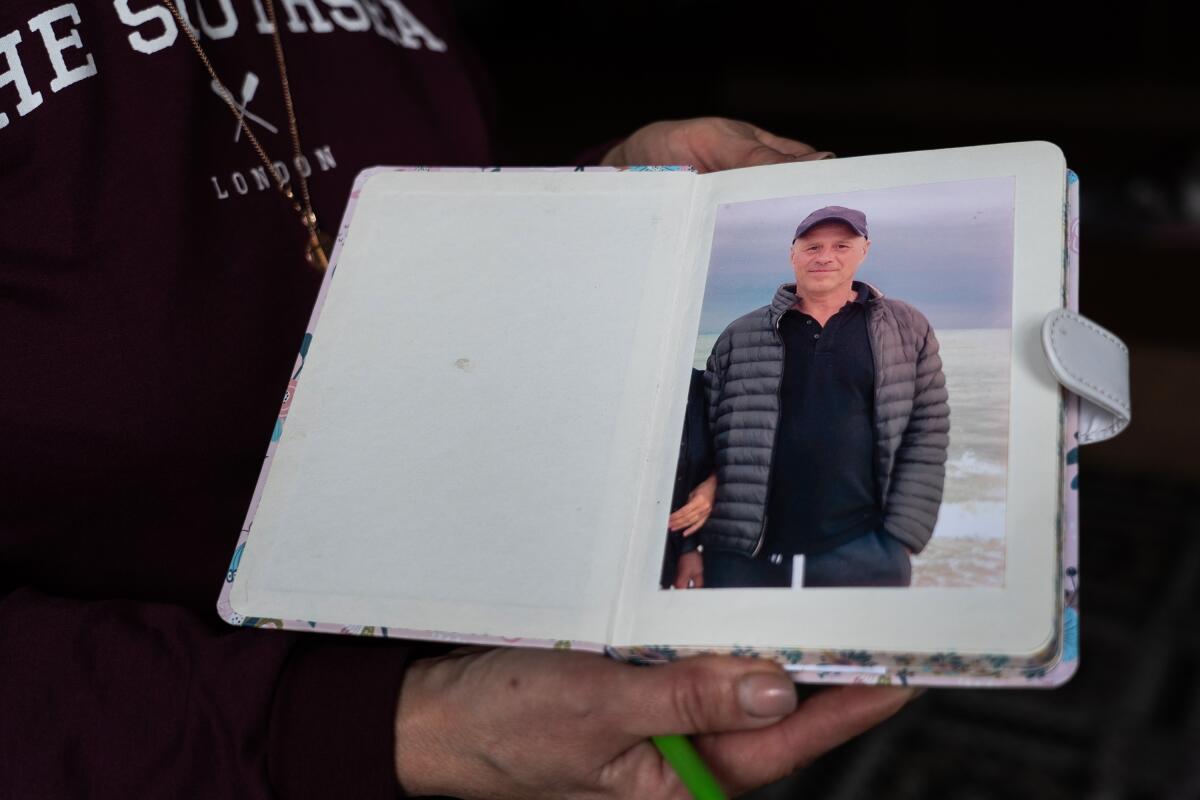

At 49, Olena has black hair, a sturdy build, and a face that can sometimes look much younger, or much older. She and Oleh grew up in these rural flatlands of southern Ukraine, where they ran a family farm and raised their two sons. They were married 30 years ago this year.

1

2

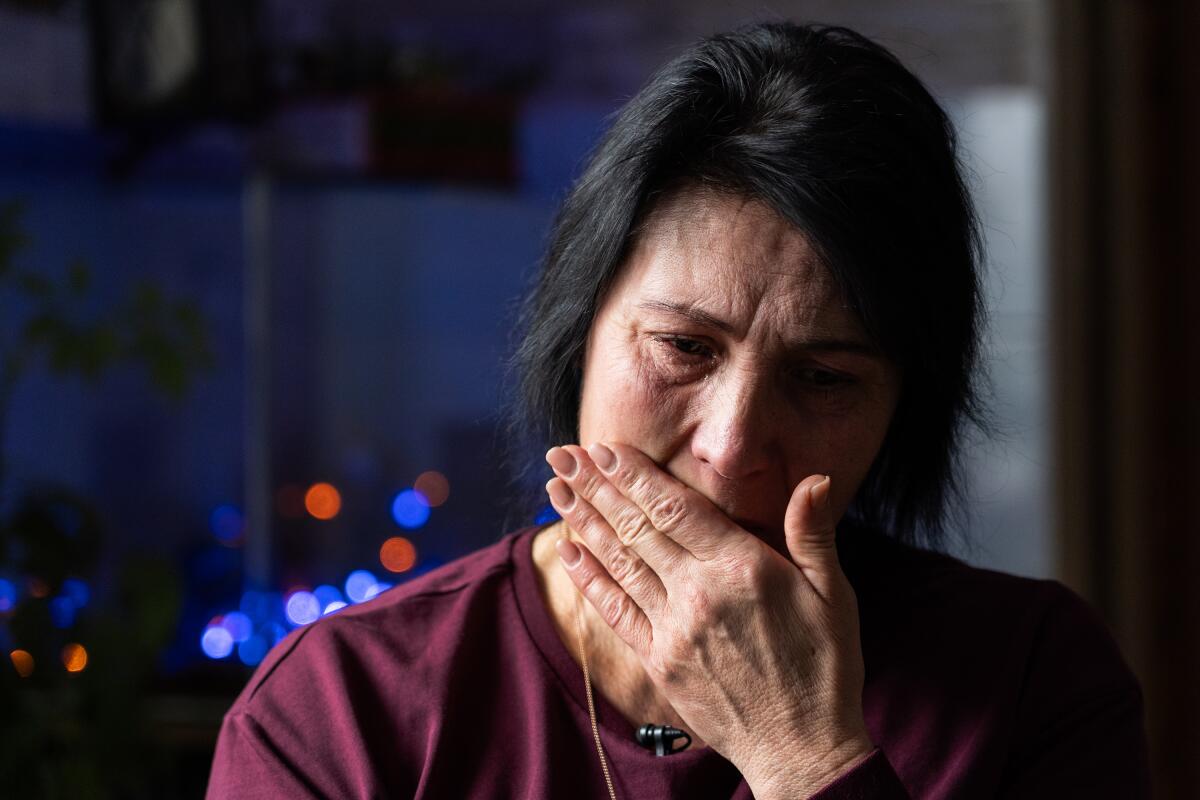

1. A picture of Oleh Kovalyk, Olena’s husband, who disappeared on April 9, 2022. 2. Olena holds back tears as she talks about her husband’s disappearance. (Anna Tsyhyma / For The Times)

The provincial capital, Kherson, about 100 miles to the southwest, fell to the Russians in the opening days of the full-scale invasion that began Feb. 24, 2022. Their village, Myrolyubivka, was swiftly overrun as well. Together, the couple made the risky decision to remain, watching over their property and hoping for liberation by the Ukrainian army.

During the first days of the Russian presence, Olena and Oleh watched from behind their gates as soldiers set up checkpoints, patrolled the streets in armored vehicles, dug trenches, took over empty homes.

Soon enough, the occupation turned personal: Armed troops repeatedly raided their home, insisting that weapons were hidden there. The Russians knew that one of their adult sons had served in the Ukrainian military, during the fight against Russia’s proxy militias in the eastern Donbas region that began a decade ago.

At their parents’ urging, both sons slipped away early in the occupation. But Oleh began taking more and more chances.

After Russian soldiers tore down the yellow-and-blue Ukrainian flag from the village council building in the center of the town, Oleh waited for a day when there were no occupying forces in sight. He found the discarded flag, brought it home and hid it inside a wall of the farmhouse, plastering over the hole.

Olena remembers him telling her then that if he wasn’t around when the village was liberated by Ukrainian troops, she should fetch the flag from its hiding place and hang it back up.

In Russian-occupied towns and villages, a small act of defiance like secreting away a Ukrainian national symbol could bring harsh punishment. But Oleh was only getting started; like many civilians in occupied towns and villages across Ukraine’s south and east, he began acting as a spotter for the Ukrainian military, relaying information about the movements and activities of the Russians and their proxies.

On April 9, nearly a month after the Russians took over the village, Oleh left the house after lunch with his cellphone, heading for an area where he thought he could get a signal.

He didn’t come back.

Olena’s search began the next morning.

With a friend, she went to a nearby agricultural enterprise known as the Valentina farm, where she thought Oleh had gone. There, they were met by an armed member of a Russian proxy militia, who warned them not to come back.

But perversely, the threat carried a glimmer of hope.

“If you see your husband,” the man told her, “tell him we are looking for him.”

Meanwhile, Oleh’s 78-year-old father, Stepan Kovalyk, went to the Russians’ local headquarters to ask after his son. Instead, he found himself detained.

The Russians threw a bag over the old man’s head, beat him and drove him to a neighboring village, where they spent hours interrogating him. Before dumping him back in Myrolyubivka, they offered a chilling coda.

“Your son is gone,” they said.

Oleh, his wife and father later learned, had been captured almost immediately after arriving at the Valentina farm buildings. This was frightening news, but Olena had heard that the Russians sometimes ransomed detainees for cash.

So she waited and hoped. But the situation quickly grew desperate.

Russian soldiers kept returning to the couple’s house, ransacking it for weapons, becoming more and more violently menacing when they found none.

After the 16th such raid, Olena decided it was time to seek shelter elsewhere, at least for now.

On April 29, she left the village through one of the only checkpoints left in the region, heading for the Ukrainian-controlled city of Kryvyi Rih, 60 miles to the northwest.

As Olena fled, the outside world was just beginning to learn of the horrors taking place in Ukrainian towns and villages under occupation.

That spring, as Russian troops broke off an attempt to seize the capital, Kyiv, the names of suburban communities like Bucha became synonymous with stories of Ukrainian civilians tortured and murdered.

In the south of Ukraine, the same bleak pattern was unfolding. In a village called Bilyayivka, a dozen miles from Myrolyubivka, the Russians turned a village school into a torture center.

Human rights organizations believe at least 20 Ukrainian prisoners were held at the school between April 2022 and the end of that September, when the village was liberated by Ukrainian troops.

It was July when two former prisoners from the school holding cell reached out to Olena. They had seen Oleh, they said. And they told her what they had witnessed.

On the second floor of the school complex, a tiny, windowless storage closet served as a holding cell. In what were once classrooms for preschool and elementary students, Russian troops administered beatings and electric shocks to prisoners’ genitals, and carried out mock executions.

Two Ukrainian groups, the nonprofit Reckoning Project and the Human Rights Center ZMINA, would later document conditions and events at the prison based on testimony from those who were held there.

According to those accounts, Russian soldiers brought Oleh to the upstairs holding cell and threw him inside. It was April 9, the same day he had been captured.

1

2

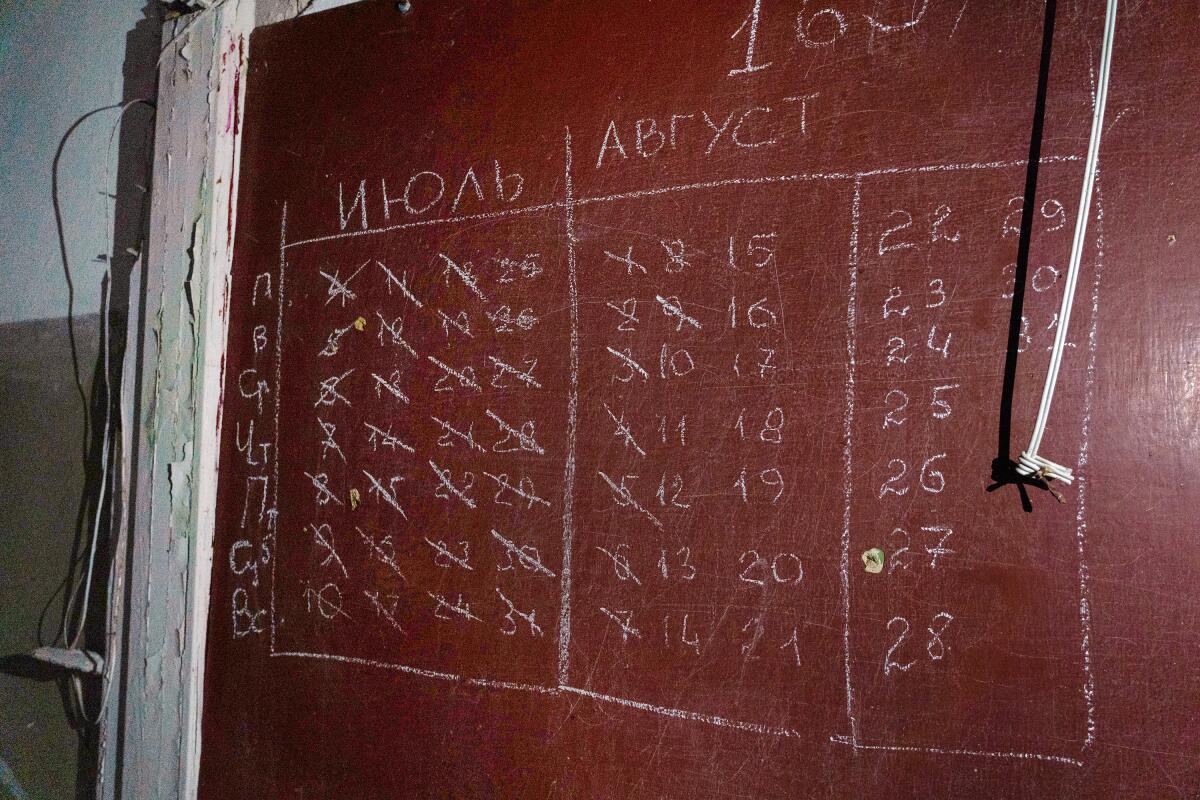

3

1. Bloodstains appear on the wall of a windowless room at the school-turned-prison in Bilyayivka. 2. An old handwritten calendar on a classroom chalkboard there. 3. Olena Kovalyk stands next to rickety wooden bunks at the makeshift prison. (Anna Tsyhyma / For The Times)

He was soaking wet, hands bound behind his back, his clothing torn. His sweatpants were cut away in the groin area. The Russian soldiers slammed the door shut, warning the 12 other men in the cell not to untie Oleh’s hands, or they would face a similar fate.

In their telling, he lay crumpled and moaning on the concrete floor, begging for water, mumbling that he had a burning sensation around his nose and mouth.

Oleh smelled strongly of strange chemicals, the witnesses recounted. They suspected Russian soldiers had sprayed a fire extinguisher into his face, a method of torture that has been documented in testimonies from other Russian-occupied areas.

At one point, a prisoner called out to guards that the bound man on the floor was dying. One of them replied that if he wasn’t dead by morning, a doctor would come.

It didn’t take until morning. According to the testimonies, it took about another half-hour for Oleh to die.

Through the haze of hearing this hammer-blow news, Olena seized upon the details that would galvanize her search in the months to come.

That next morning, surviving prisoners said, Russian soldiers opened the cell door and saw that Oleh was dead. They ordered two other prisoners to stuff the corpse into a big white fertilizer bag and heave it into a Russian armored personnel carrier.

Months later, those prisoners said their first thought was that they would be asked to bury the body. But then they heard one of the Russian soldiers say, “She’ll pay us for this.”

At the time, the witnesses took the Russians’ comment to mean they would try to extort money from the man’s widow.

In one sense, though, the captor’s prediction was correct: Olena would pay.

And pay, and pay.

Olena returned to her home in Myrolyubivka in late September 2022, just weeks after a Ukrainian military counteroffensive recaptured a swath of territory that included her village and the surrounding area.

By that time, more information was trickling out about the Russian torture chambers and prisons in the Kherson region. Olena was determined to speak to as many witnesses as she could. Any clue might help her find the body.

Time made those clues harder to come by. Of the dozen prisoners who were in the cell with Oleh, one hanged himself, and another died of a heart attack, according to the Reckoning Project. A third was killed in subsequent shelling. A fourth told her he could not bear to speak about what he witnessed.

Olena turned to the police and other security agencies to help with her search, but described the response as frustrating. One security officer, she said, urged her to concentrate on the bureaucratic task of obtaining a death certificate to collect widow’s benefits.

“What money?” she said angrily. “I said I needed his body.”

She described ordering the officer off her property, but only after demanding a thorough official search for Oleh.

“How can I find him myself?” she asked.

That task, as it turned out, became her life’s work.

About once a week, Olena returns to Bilyayivka, site of the school-prison, to walk the village pathways and look for any signs of disturbed earth that could indicate a burial site.

She follows every lead, no matter how small. Last year, she heard a rumor that during the occupation, bodies were buried in a walnut grove just outside a neighboring village.

But Ukraine is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world, and Olena knew it would be near-suicidal to venture into the orchard. She began agitating — so far unsuccessfully — for sappers, or de-mining specialists, to clear the grove.

She has tried to enlist allies wherever they might be found. Last September, she appeared on a war-crimes panel in Kyiv, with the prosecutor general, Andriy Kostin. She made an emotional appeal for his help; the regional prosecutor’s office is now involved.

“There are so many cases like this!” she said. “Maybe they would like to say they will solve it all. But it’s not realistic.”

The most frightening prospect, she says — one that she can hardly stand to contemplate — is that the Russians might have taken the body with them when they pulled back from the area.

Still, some help has materialized. Local Ukrainian journalists have published accounts of her search, which attracted the attention of volunteer and civil society groups. An organization called On the Shield, which specializes in searching for fallen soldiers, brought in dogs and handlers to comb the grounds of the school-turned-torture center.

Foreign nongovernmental organizations are stepping in to help Ukraine develop systems and methodology for searches like this one. But with at least 30,000 people unaccounted for, by Ukrainian estimates, the task is enormous.

“This limbo, yes — the United Nations has called it a form of torture,” said Kathryne Bomberger, executive director of the Hague-based International Commission on Missing Persons, which is helping Ukraine build a missing-persons tracing system to international standards.

Since the organization began its work during the Balkan wars of the 1990s, she said, there have been enormous technical strides including DNA matching, but the emotional backdrop remains an agonizing constant. People like Olena, Bomberger said, “have a right to justice, to truth, to knowing.”

Olena now has a companion in her quest: a Ukrainian civilian-military liaison officer assigned to the region. Tall and blunt-featured, his name is Serhiy, and in keeping with Ukrainian military protocol, he asked not to be further identified.

On a cold January day, he walked with her, retracing paths they had covered many times before: black earth, white patchy snow. Flickering in her mind’s eye was a white fertilizer bag.

When Olena recited a long list of nearby places she thought they should search as well, Serhiy listened, nodding.

Olena has talked to everyone in Bilyayivka who is willing to speak. She asks them all to turn their minds back to the days of occupation, to consider any obscure location where a body might have been dumped.

But for villagers still struggling to recover from their own ordeals from that time, it’s a big thing to ask. She knows that.

On this day, Olena led Serhiy to a large sunken concrete pit across the street from the school building. Such holding tanks, dating back to the Soviet era, are scattered throughout the village, probably originally used for collecting rainwater.

Before the war, the area abutting the school had been a little park, complete with burbling fountain. Now it was strewn with trash: empty bottles and cans, pieces of tattered Russian uniforms. One of the concrete pits was full of empty shell casings.

Isn’t it strange, she asked Serhiy, that the area is so covered in litter? As if concealing something?

He responded sympathetically, but didn’t give the answer she hoped for. The pits were deep, he noted, and clearing them would require special equipment. Moreover, they could very well be mined.

“Sometimes I ask myself: If I find him, will it get easier for me?” Olena said.

Even now, she cannot help envisioning him alive. He would be 51 now. Whenever there are televised scenes of prisoners brought home in exchanges, she studies the faces intently.

She pays close attention to her dreams. In one particularly vivid one, she saw Oleh descending a wide stairway with a green carpet. She recognized it immediately: the interior of the Bilyayivka village school.

Perhaps, she said, the prisoners’ recollection of Oleh’s death was all a mistake. Perhaps he will come home. She twisted a handkerchief, looked down at her hands.

“There are no miracles, I understand,” she said quietly. “But hope is the last to die.”

She still has the flag Oleh had rescued. Olena and her sons dug it out of the wall of her half-ruined home. She said she had promised her sons she would raise it as her husband had asked — but only after she found his body.

Times special correspondent Ayres reported from Bilyayivka and Myrolyubivka, and staff writer King from Berlin. Some of the reporting for this story was supported by the Reckoning Project, a consortium of Ukrainian and international journalists and researchers who record and verify witness testimonies of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.