‘Syrians will go!’ As Turkey’s election runoff nears, refugees face new threats

- Share via

ISTANBUL — In the mobile game “Zafer Tourism,” players catapult Syrian refugees scurrying into Turkey onto trucks to take them back from where they came.

“Protect your borders. Don’t let them pass,” says a description on the Google Play store.

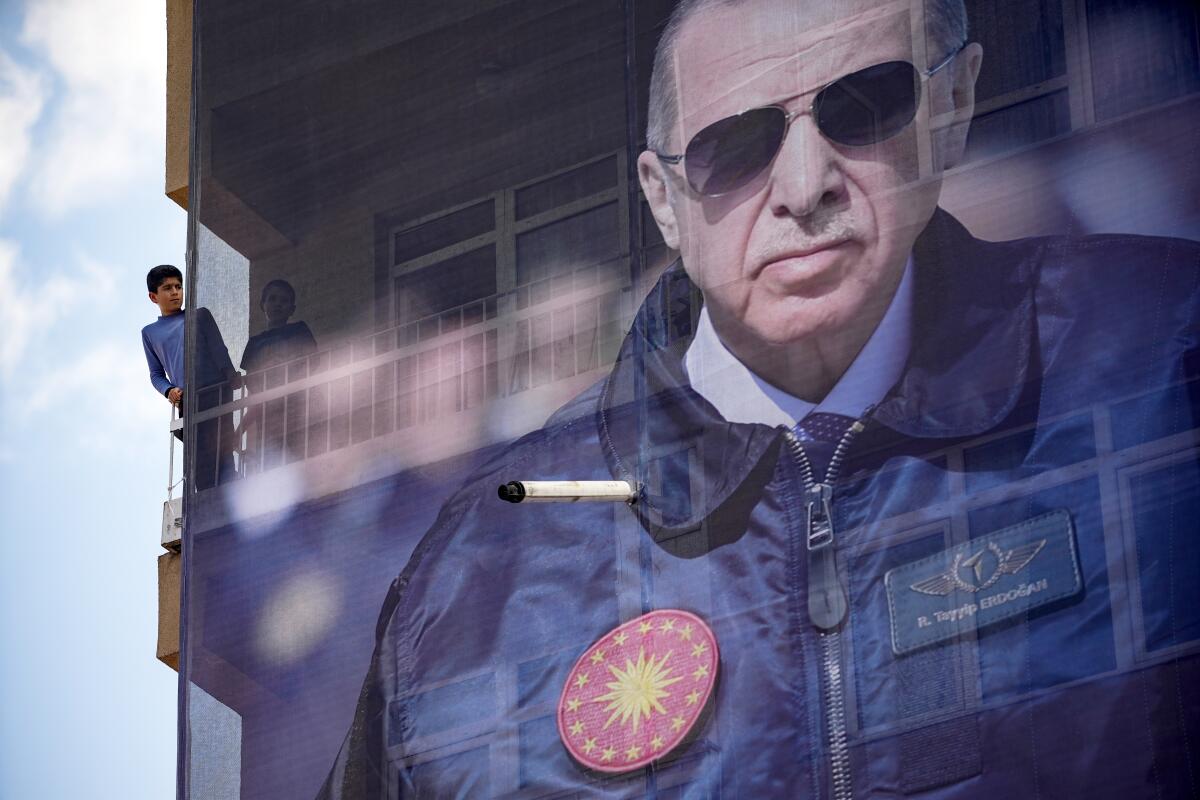

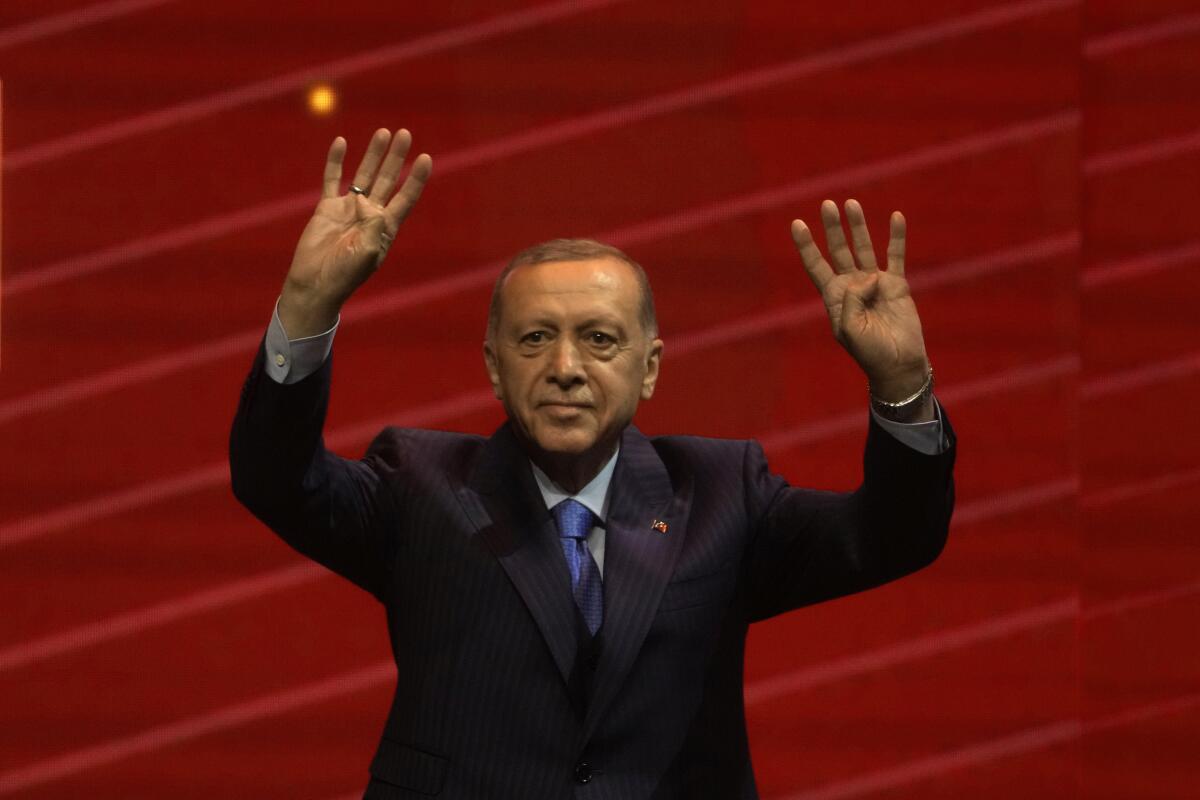

The game, whose name refers to an anti-migrant campaign by the Turkish far-right Zafer (Victory) Party, was released by Turkish publisher Gacrux Game Studio in September but has since gained attention amid the tight election tussle between longtime Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu. Sunday’s runoff is increasingly focused on the fate of the roughly 3.7 million Syrian refugees in Turkey.

The first round saw Erdogan get 49.4% of the votes while Kilicdaroglu received 44.96%; a third contender, Sinan Ogan, a hard-right figure who has made sending refugees back a central theme of his campaign, made a surprisingly strong showing with 5.17%.

Now, the two remaining sides spend the days to the runoff courting ultranationalist voters they hope will give them the push to victory.

For populist Erdogan, 69, this has meant a switch from terming calls to repatriate Syrians as inhumane and contrary to Islamic values to a statement on CNN Turk on Tuesday emphasizing that his government had already sent back more than half a million Syrians, with more to follow.

For the soft-spoken Kilicdaroglu, 74 — he was billed as Turkey’s Gandhi — it has meant replacing his nice-guy image with a sharp-elbowed persona meant to demonstrate how tough he can be on migrants.

“We will never, ever make Turkey a warehouse of refugees,” Kilicdaroglu said in a campaign speech Tuesday in Hatay, the earthquake-hit province on Turkey’s southern border with Syria, adding that people should act before “refugees take over the country.”

That followed a Twitter campaign video released Saturday in which he said, “As if 10 million Syrians aren’t enough, will you let 10-20 million more come?” (Before the first round, he had said the number of Syrians in the country was 3.7 million.)

Kilicdaroglu also vowed to repatriate Syrians as soon as he is elected — it’s unclear if it would be on a voluntary basis — and renegotiate a 2016 deal with the European Union in which it paid Turkey billions of euros to thwart refugees from reaching European shores. His campaign posters, meanwhile, announce, “Syrians will go!”

“There has been a radical change in Kilicdaroglu’s tone,” said Halil Nalcaoglu, a communications professor at Istanbul’s Bilgi University.

“He ran a positive campaign in the first round, but it just didn’t work. Refugees wasn’t the main agenda, but it has become so because of pressure from different circles, which means he has to sell the idea that he can be very harsh on refugee policy,” he said.

Since last week’s earthquake, refugees of Syria’s civil war living in Turkey have faced growing anger from those who see them as a burden and blight.

Omar Kadkoy, an expert on migration at the Ankara-based think tank Tepav, said the opposition had expected the country’s economic woes to have had more of an influence on voters.

“When you fail as a politician to convince potential voters from across the political spectrum with your own program — which focused on human rights and economic issues — then you have to resort to this populist discourse,” he said.

The tactics appear to have had at least some effect. On Wednesday, Kilicdaroglu won the endorsement of Zafer Party head Umit Ozdag, a hard-right figure who puts refugee figures at 13 million and has funded films that characterize the migrant influx as a “silent invasion” that will make Turks a minority.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

At the same time, third-place finisher Ogan — who had conditioned his endorsement on a more stringent policy against refugees and Kurdish groups he counts as terrorists — came out in support of Erdogan this week. It’s unclear what he asked of Erdogan, who is widely expected to win the runoff, in return for the endorsement, but the resonance of the anti-refugee rhetoric with eligible voters, nearly 90% of whom participated in the first round, has not gone unnoticed.

Erdogan, while changing positions himself, has taken particular aim at Kilicdaroglu’s about-face.

“If you want to define the lie, you have to look at Kilicdaroglu. On what basis do you say this 10 million [refugees]? He’s trying to save the day with hate speech,” Erdogan said.

When Syria first descended into civil war in 2011, millions fled the violence to neighboring countries including Lebanon and Jordan. But it was Turkey that took the lion’s share of refugees, granting privileges — the right to work, access to education and healthcare, among others — that were denied to them in other host nations. Turkey, under Erdogan, also supported Syrian rebel fighters, allowing them to use Turkish border cities as supply depots and staging grounds for attack on Syrian government forces. Erdogan also insisted Syrian President Bashar Assad had to step down.

But as the Syrian civil war stretched on and Assad — with Iranian and Russian help — remained in power, the welcome soured.

An ongoing economic crisis that began in 2018 has bred resentment against Syrians. Inflation peaked at 80%, though it has since fallen to slightly more than half that figure overall, and experts say it remains in the triple digits in large urban centers. Then came the devastating earthquakes in February.

Though Assad has clung to power, Syria remains fragmented, and a series of U.S., EU and United Nations sanctions are still in place that prevent rebuilding. He has also conditioned any talks regarding repatriating refugees from Turkey on Ankara pulling its forces from Syria’s north. For many like Ziyad, a 25-year-old from the Syrian capital, Damascus, the idea of being deported to Syria is untenable.

Polls show Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan facing the toughest reelection race of his career as the country prepares for an election Sunday.

“I have a work permit. A license. All from the Turkish government, and I’m 100% legal,” he said. Ziyad came to Turkey eight years ago and now works in an electronics store in Istanbul’s Fatih district, a neighborhood with one of the city’s largest Syrian communities. He gave only his first name to avoid reprisals.

“Every day, you see policemen here stopping people at random, asking them for documents,” he said. “They picked up a guy yesterday from the barbershop he owns. If they suspect any wrongdoing, they take you to a deportation center; 12 hours later you could be in Syria.”

That almost happened to the family of Lujain, 30, a woman from Damascus who came to Turkey in 2011 and received citizenship after university studies there.

Her family runs a hair transplant clinic, and a client had forgotten his passport, so her father offered to take the man back to his hotel to get his documents. But when police stopped the car, the officers accused her father of smuggling refugees. They sent him to a holding center and it took two lawyers, $9,000 and more than a week in detention for him to be released. Even so, the deportation order still stands, meaning he could be kicked out of the country at any moment.

The deadly earthquake that struck southeast Turkey and northern Syria has devastated areas that are home to millions of Syrians displaced by war.

“I try to believe nothing will happen to us here, that if I don’t harm anyone then no one will harm me. But at the same time, my father tried to do a small favor for someone and now we have this issue, so you know in this country that you’re never, ever secure, that anything can happen,” Lujain said.

The opposition has vowed to look into citizenship recipients like Lujain — raising the specter of Syrians like her losing their Turkish passports.

“For me, if I lose my papers, I’ll figure it out, but my parents are old and we have no one left in Syria,” she said. “We already had one nationality that lost value. Now this one could as well.”

As for the Zafer Tourism game, on Friday, a Google representative confirmed the app was no longer available on the Play Store since it violated Google Play’s policies on promoting violence and inciting hatred.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.