- Share via

MISSION, Texas — There was the teenager from Texas. The father from San Diego. The runner from Indiana.

They went for a day trip. Or a wedding. Or a winter vacation. But they all died after taking counterfeit pain pills purchased at drugstores in Mexico. And they all got those medications in the more than three years between the time the federal government learned of the threat and officials finally warned the public.

A Times investigation published last month showed that both the U.S. State Department and the Drug Enforcement Administration have known since at least 2019 that some pharmacies in Mexico are selling pills made of powerful drugs such as fentanyl and methamphetamine and passing them off as legitimate pharmaceuticals.

But the State Department didn’t post a health alert until after congressional lawmakers called for the move last month in response to reporting by The Times. The DEA has yet to take public action to combat the problem.

In the interim, travelers from across the U.S. overdosed after buying counterfeit versions of medications such as oxycodone and Adderall from mostly small, independent pharmacies in Mexican tourist towns and border cities. Some people who took the pills survived, and some — such as Ryan Bagwell — didn’t.

His mother, Sandra Bagwell, wishes she’d known about the risk.

“Why did they keep that information from us?” she asked during an interview at her Mission, Texas, home. At the least, she said, she could have warned her son, or ordered him not to go. “Maybe he would still be alive.”

A DEA spokesperson provided a brief emailed statement in response to a list of detailed questions about the deaths and the agency’s failure to notify the public sooner.

“Every life lost to a drug poisoning is tragic,” the statement said. “DEA investigates all leads and works with our federal, state and local partners to pursue

investigations ... and we continue our education and outreach efforts on this important issue to save lives.”

A State Department spokesperson also provided a statement via email.

“We generally publish information on health considerations for U.S. citizens abroad in our Country Information pages and not in our Travel Advisories,” the statement said, after noting the two advisories the department issued last month. “Our Country Information Page for Mexico has advised U.S. citizens to exercise caution when purchasing medication overseas for some time.”

The Times has found at least half a dozen troubling incidents, but the lack of reliable data makes it difficult to determine how many people have been harmed. It’s not always clear to investigators what pills people have taken, or where they came from. And drug market experts say Mexico’s mortality data vastly undercount overdose deaths — in part because the country’s high number of homicides has created such a backlog that many autopsies are conducted without advanced toxicology testing.

Pharmacies in several Mexican cities are selling counterfeit prescription pills laced with fentanyl and meth and passing them off as legitimate pharmaceuticals.

Lt. Christopher Olivarez of the Texas Department of Public Safety has been on the front lines of the fentanyl crisis as it has exploded in recent years. He said he “can almost guarantee” that there are numerous cases of travelers killed by fentanyl-tainted pills purchased from Mexican pharmacies that will never be known.

“A lot of these cases probably are happening or have been happening, and we don’t know about it because they’re not being reported,” he said. “And there’s no awareness and no education on it.”

It was Ryan Bagwell’s third time walking into Mexico. The 19-year-old and a friend were going to hang out across the bridge in Nuevo Progreso, a small border town just a 45-minute drive from the Bagwells’ home in Mission, a city of 80,000 in the southern tip of Texas.

Sandra Bagwell had hoped the family would get lunch together that afternoon, but when her son said he wanted to make a day trip across the border, she didn’t think anything of it. Though he could be a troublemaker, she said, he was generally a good kid.

Born on Christmas Eve 2002 in Las Vegas, Ryan had always loved to party. By the time he was in his mid-teens, his family had caught him sneaking out of his bedroom window at night. But he’d never gotten into serious trouble. And if he’d been using hard drugs, his parents had seen no obvious signs of it.

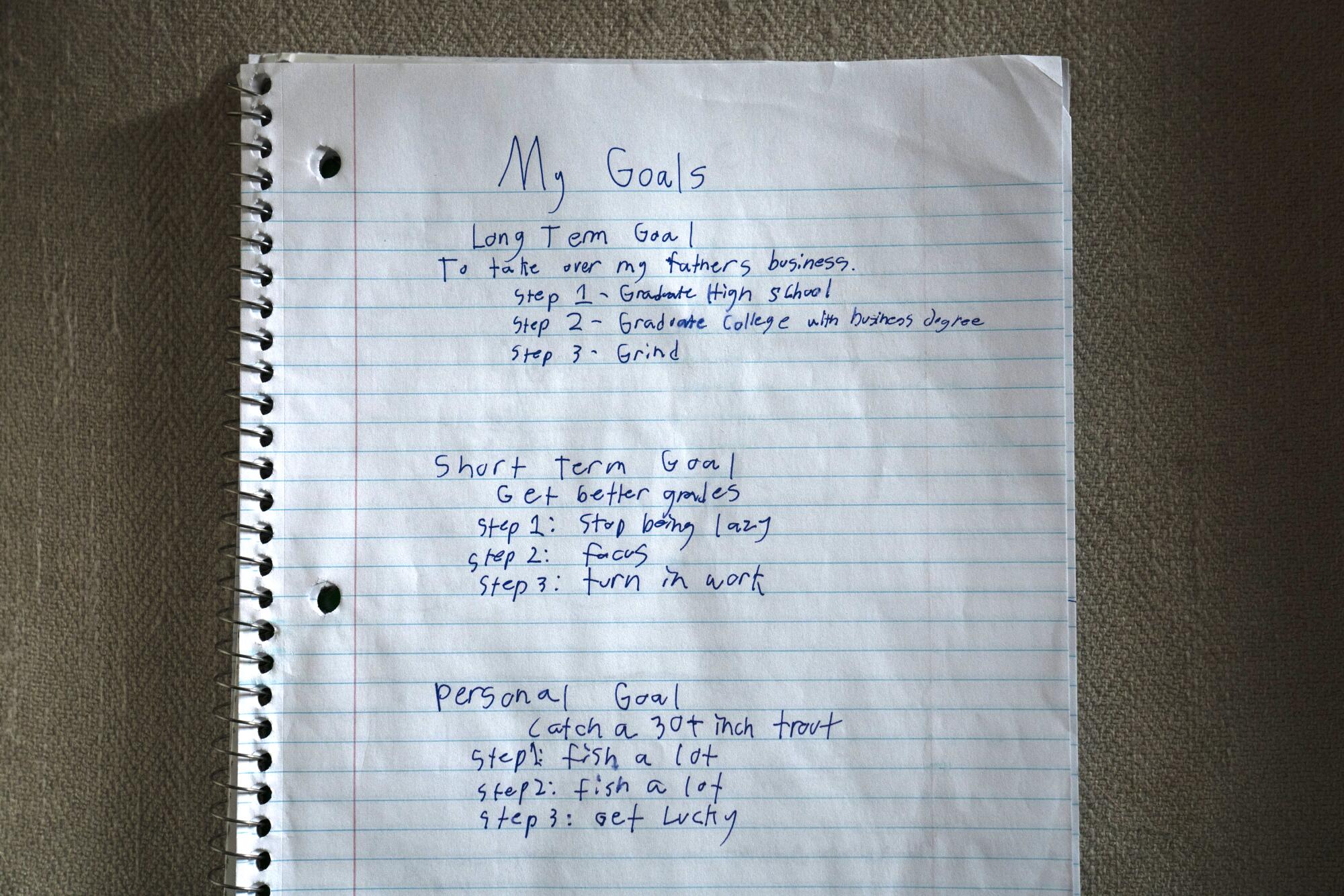

He had big ambitions. A list scrawled in blue ink on lined paper that his mother found among his belongings after he died identified three clear goals: get better grades, catch a 30-plus-inch trout and “take over my father’s business” selling manufactured homes.

Bagwell assumed that if Ryan spent a day across the bridge, he might grab a few tacos or take advantage of the lower drinking age to enjoy a beer or two.

But a little after lunchtime on April 3, 2022, he stopped at a pharmacy and picked up what he thought was Percocet. He shared a video of the white plastic bottle on Snapchat. He snuck the pills across the border and was back at his parents’ house by sundown.

“He came home that night in a great mood,” his mother said.

After a cursory greeting, he went up to his bedroom with some takeout dinner and shut the door. His sister texted him to see if he wanted to do something. He replied that he had a headache but suggested they hang out the next day. It was the last text he would send her.

Later that night, he shared a video on Snapchat of himself in his bedroom taking a yellow tablet.

The next morning, Bagwell realized there was something wrong when she found out Ryan hadn’t shown up for work at his father’s business. She wasn’t home to check on him, so she called their housekeeper and asked her to knock on his bedroom door.

“There was no answer, and at that moment I knew. I knew something horrible had happened,” Bagwell said. She rushed home, ran upstairs and pushed open her son’s unlocked door.

“He was there, laying on his side,” she said. “I knew he was gone. His face was swollen, there was blood and vomit coming out of his nose, he had the spots on his body already.”

It’s not just border cities that have seen deaths and overdoses from fentanyl-tainted pills bought in Mexican pharmacies.

Were you or someone you know harmed by pills in Mexico?

We want to hear from readers about their experience. Let us know by filling out this brief form.

The 2019 case that wound up on the DEA’s radar stemmed from a purchase some 600 miles south of the border, in the tourist town of Cabo San Lucas. There, 29-year-old produce broker Brennan Harrell and a friend visited a drugstore where they bought what they thought was oxycodone. It turned out to be fentanyl, and hours later the Ventura County native died in his hotel room.

Afterward, Harrell’s grieving family cooperated with the DEA, and investigators spent months looking into his death — but they did not tell the public. The U.S. State Department, meanwhile, added to its website only vague language about the prevalence of “counterfeit medication” in Mexico that didn’t mention pharmacies.

For nearly four more years, American visitors to Mexico remained unaware of the dangers. They visited pharmacies and bought medications. Sometimes, they died.

In late 2020, an Indiana man — whose family asked that he not be named — went to a pharmacy during a visit to Cabo. He was a runner, and Adderall helped him focus enough to balance his athletic pursuits with a grueling academic schedule.

But after he bought a combination of pills during his trip that December, he died of an overdose on the flight home. An autopsy found that a combination of fentanyl and methamphetamine had killed him.

In the late spring of 2021, a couple from Leimert Park visited Puerto Vallarta for a vacation. A few days after they arrived, one of the men — David Fitzpatrick, now 47 — got stung by a bee. It was the first time he’d ever been stung, and it developed into something far more painful than he expected. So he walked to a nearby pharmacy and asked the clerk for help.

“I told her I needed something for pain,” he told The Times.

A Times investigation found that some farmacias in Mexican tourist towns are selling prescription drugs laced with fentanyl and methamphetamine. The question is, why?

A few minutes later, he walked out with a blister pack of 20-milligram oxycodone tablets.

He and his husband, Eric Schab, work in healthcare, and Fitzpatrick had taken oxycodone before. So he knew what the pills normally feel like, and both knew what the usual effects would be.

But when Fitzpatrick took one of the pills the pharmacy had sold him, he blacked out. He had to be carried back to their hotel room, where he was belligerent and incoherent, at times rolling around on the floor, until eventually he fell silent.

“He was just completely out of it,” Schab said. “I have never seen anything like that before.”

As he struggled to figure out how to get help, Schab decided to get rid of the pills — and as soon as he dumped them in the toilet, they “started to effervesce like an Alka-Seltzer.”

Because he didn’t save any, he and his husband never got the pills tested and never reported to authorities what happened. But two years later, they’re both confident that the tablets Fitzpatrick took were something stronger than oxycodone.

Last summer, 39-year-old Matthew Kramer — a lawyer and father of two from Granada Hills — went to Ensenada, Mexico, for a wedding. On the way back, according to his family, he stopped at a pharmacy to pick up some medications.

He was found dead in a Carlsbad hotel room the next day.

His parents waited months for the autopsy and toxicology results. It wasn’t until this year that they learned there were methamphetamine and fentanyl in his system.

“I miss him so much,” his mother, Rosalinda Kramer, said. “There are so many people losing people they love — it’s devastating. It’s like there’s a pall of sadness over all of the parents in this situation.”

How many there are is impossible to tell. In addition to the Harrells and the families in Indiana and Texas, The Times reviewed cases of people in Colorado, Arizona and Orange County who believe their loved ones may have died from tainted pills purchased at Mexican pharmacies.

But their suspicions are tough to prove: Most travelers don’t carry around drug tests, and most grieving families never find out where a fatal dose came from.

The day Ryan Bagwell died, Mission police officers spent hours searching his room. According to his mother, they found weed and smoking supplies — but not the pills he’d posted on Snapchat.

It wasn’t until three months later that she found an unfamiliar medicine bottle while going through her son’s things.

She was surprised to discover that local police had missed it. But by that point, she said, they’d told her the case was closed. The police had done all the investigating they could, their probe limited by the fact that they were unable to get past the lock screen on Ryan’s cellphone.

The Mission Police Department did not respond to requests for comment via phone and email.

With new evidence in hand, Bagwell got creative. She had a friend whose husband was a retired Texas Ranger, and she hoped he could help bring in federal investigators.

“And that’s when the DEA took over,” she said.

After a Times investigation found medications in some Mexican pharmacies tainted with fentanyl and methamphetamine, officials call for action.

According to Bagwell, federal investigators spent months working to unlock her son’s phone and analyzing its contents. They conducted a series of interviews, she said, including one with the friend who’d accompanied Ryan to Nuevo Progreso, who told authorities they’d visited two pharmacies that day.

One of the two stores, Bagwell realized, had been the source of the unfamiliar bottle. It said “Percocet,” and most of the label was in English. But when she looked closer, she noticed that the expiration date was in Spanish.

Alarmed, she turned it over to the DEA.

“They tested the pills,” she said. “That bottle was fentanyl.”

Ultimately, she said, investigators told her what they thought had happened: Her son had stopped at two drugstores in Nuevo Progreso, picking up Xanax at one and Percocet at the other. While the Xanax may have been legitimate, the Percocet was not.

Toxicology testing did not show oxycodone in his system. Instead, there was fentanyl.

U.S. authorities have known for years that Americans have died after consuming counterfeit pills containing fentanyl purchased from pharmacies in Mexico.

But even though the investigators had figured out what had killed Ryan, they said there was not much they could do in response, according to his mother.

“I just feel like they could have done more,” she said. “Close that pharmacy. Stop other people from buying pills from that particular pharmacy. I know there’s pharmacies everywhere, but to me, that would be some kind of justice.”

At the very least, “there should have been a warning a long time ago,” she said. “It could have saved so many lives.”

The warning didn’t come until last month, when the State Department posted on its website a health alert notifying travelers that counterfeit pills containing fentanyl and methamphetamine “can be purchased at small, non-chain pharmacies in Mexico along the border and in tourist areas.”

By then, for the Bagwells and other families, it was too late.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.