- Share via

KYIV, Ukraine — Tulle and taffeta, garlands and lace: Some nuptial trappings, at least, have survived the nearly 6-month-old Russian invasion that has upended virtually every aspect of life in Ukraine.

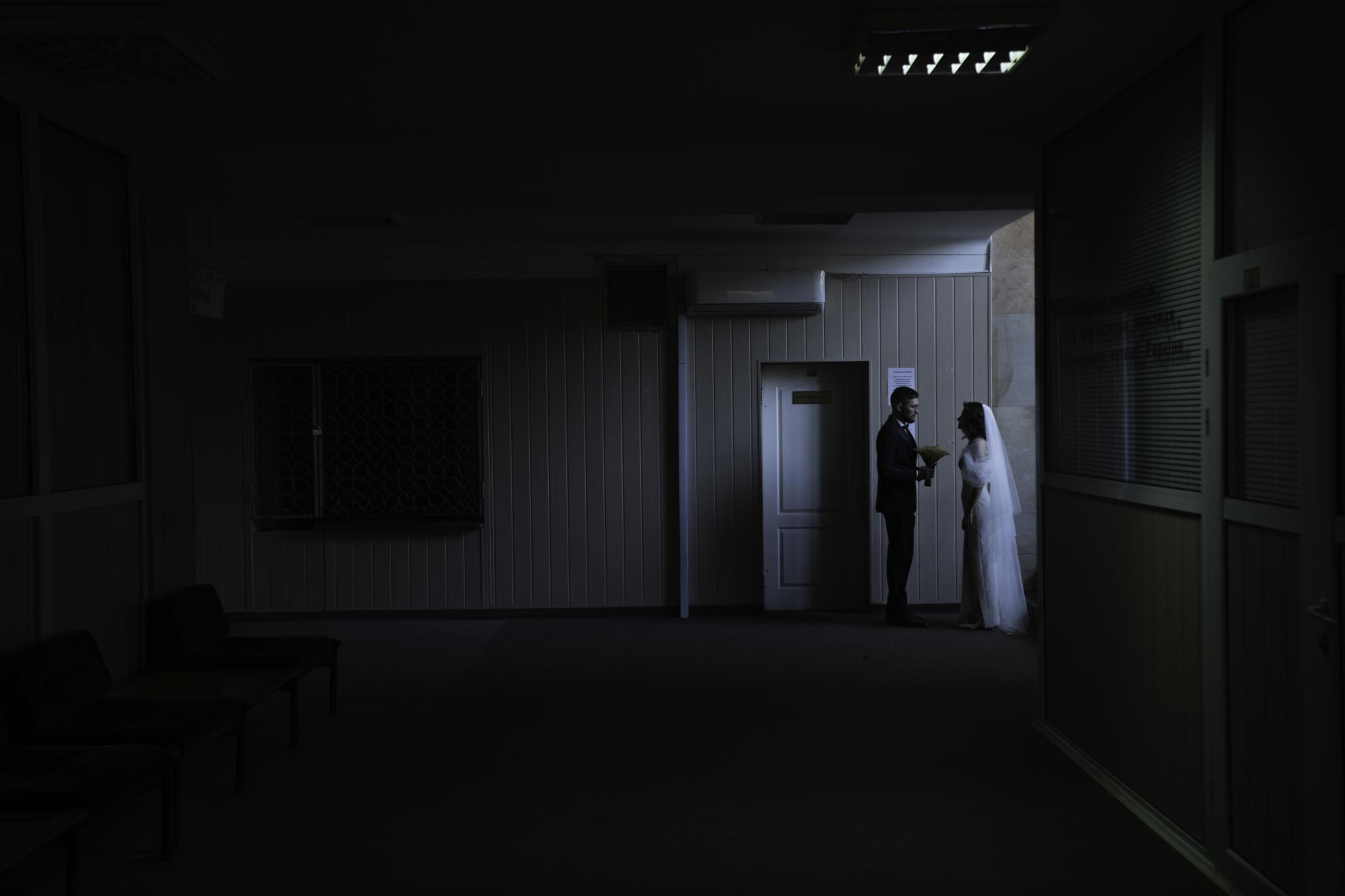

But the matrimonial scenes that unfold near-daily at Kyiv’s main Civil Registry office — their numbers swelling rapidly after a hiatus in the conflict’s first few months — are also an emblem of war’s vicissitudes.

For many couples, what might have been in peacetime a days-long extravaganza, with endless traditional toasts and a horde

of dancing relatives and friends, is compressed into a moment where a few family members witness a hasty exchange of vows and a kiss during a break from front-line duty.

“Even though this is a completely different event than it would have been otherwise, we didn’t want to postpone any longer, not even for a day,” said Inessa, a 26-year-old bride with long dark ringlets and a gauzy white gown. She and her new husband, Danyl, also 26, did not want their last name used because he was heading back to the battle zone in a few days, and his father is a high-ranking military official.

The seize-the-day ethos underpinning many wartime weddings is also galvanizing calls for Ukraine to move toward permitting same-sex unions. Following a petition drive that gained countrywide impetus when many serving LGBTQ soldiers became vocal in their demands to marry, President Volodymyr Zelensky said this month that government officials were looking into ways to ensure equal rights in civil partnerships, even though the country’s constitution, which designates marriage as taking place between a man and a woman, cannot be changed in wartime.

At the same time, martial law imposed at the start of the conflict opened the wedding floodgates by allowing couples, civilian or military, to quickly apply and marry on the same day.

At Kyiv’s main registry office, bureaucratic business — not only weddings, but other civil matters like registering births and deaths — was disrupted in the war’s first months, when the capital was under threat and some of its suburbs were seized and occupied. Russian troops penetrated the city’s western edge, not far from the landmark Soviet-era main registry building.

Operations have now rebounded beyond prewar levels, according to the office, with 9,120 marriages recorded at the main registry and satellite branches elsewhere in the capital in the first five months of the war — a more than eightfold leap from 1,110 in the same period in the previous year.

Almost daily, the starting point for this chaotic yet choreographed wedding march is the registry’s parking lot, which fronts a busy six-lane road. One after another, cars pull up and deliver brides in confectionary frocks, small flower girls with outsized bouquets, and grooms who are sometimes in tuxedos and other times in khakis, crisp shirts and blinding white slip-on shoes.

Inside, couples arriving for their designated time slots mill about, waiting to be moved from an airy anteroom with ornate wrought-iron light fixtures to one of several tapestry-lined wedding halls. Taffeta rustles, the scent of flowers mixes with aftershave. Piped-in pop songs like one titled “Hello Bride” — often derided as sappy in normal settings — are de rigueur in this context.

Clipboard in hand, Daria Ripa, a registry officiant for the better part of a decade, corralled the waiting couples, offering up admonition and instruction.

“Don’t forget your chalice!” she barked. “And your ryshnik!” — an embroidered Ukrainian wedding towel.

For all her air of martial efficiency, Ripa — who wore a pink garland headband and a ruffled white blouse, in a nod to the wedding pageantry taking place, paired with jeans and sneakers, for ease in bounding up and down the wide staircase — grew emotional when she paused for a moment to talk about the couples in her temporary charge.

“Some of them will go to war and not come back — right after, they might go to the front,” she said, dabbing her eyes. “So every day, we put our soul into every couple, into making them happy.”

Brightening, she added: “Marry all day long!”

For some couples, the war crystallized vague intentions of marrying one day into a decision to proceed — love is a marker when so much is uncertain. For others, elaborate existing wedding plans, even if they had been logistically possible to carry through, clashed too harshly with a war that has displaced millions and killed thousands.

From the invasion’s earliest days, front-line weddings have been regularly conducted by military chaplains. Kyiv’s mayor, Vitali Klitschko, attended the marriage of two members of the Territorial Defense Force, held at a checkpoint outside the then-menaced capital.

Some couples consider going ahead with wedding celebrations as a display of defiance in the midst of death and destruction. In the central city of Vinnytsia, after a devastating bombardment last month that killed at least 26 people, a bride named Dariya Steniukova posed in her wedding finery surrounded by rubble in a wrecked family apartment, and posted the pictures online. The attack, on July 16, came a day before her marriage.

“We are ready to get married, even with rockets flying over our heads,” she told the French news agency AFP.

The Russian invasion and the dizzying twists and turns that followed — Ukraine initially rallying in the face of widely expected defeat, the war settling into an ugly and bloody grind in the country’s east, a gathering confrontation as Ukrainian forces seek to retake part of the southern coast — made waiting, for some, seem like an impossibility.

“All of us have found ourselves in circumstances where we do not know what will happen tomorrow, and even today until the evening,” the deputy justice minister, Valeria Kolomiets, told Ukrainian radio in April, saying that war had spurred people to formalize relationships in case the worst happened to one of them.

At the Kyiv office, a pair of 24-year-olds, Maryna and Eugene, posed for pictures as they waited their turn. He, too, was a soldier soon to return to the front, and the two had security concerns about publicizing their full names.

“We can’t postpone life, because we don’t know how long life lasts,” Maryna said. “This way, love wins.”

Eugene smiled as his soon-to-be-wife adjusted the slit in her long white skirt to show some leg.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.