Coinciding with Biden visit to Poland, Russia signals scaled-back goals in Ukraine

- Share via

LVIV, Ukraine — As President Biden visited Poland on Friday in a show of support for NATO’s eastern flank, Russian military chiefs signaled a streamlining of war aims in Ukraine — a potentially face-saving path for Vladimir Putin to exit what has become a lengthy, grinding and increasingly deadlocked conflict.

Even as Ukraine continued to tout an emerging ability to launch counterattacks against a far stronger invading force, the start of the war’s second month brought fresh evidence of the horrifying toll in civilian lives. Ukrainian officials said Friday that at least 300 people had died in a Russian airstrike this month on a theater in the encircled port city of Mariupol — apparently the war’s worst single episode of civilian fatalities.

At the same time, after weeks of silence on the subject, Russia acknowledged Friday that more than 1,300 of its troops have died in the invasion. That number, while still more than double Moscow’s previously announced tally, is a fraction of most Western estimates of Russian combat losses. NATO has estimated Russian losses to be between 7,000 and 15,000.

In pushing ahead with a war that Putin had gauged would swiftly decapitate Ukraine’s government, the Russian military leadership, beset by supply, morale and logistical problems, said its focus was now on driving Ukrainian forces back from the eastern Donbas region, where the Kremlin fomented a separatist conflict eight years ago.

The Times’ Marcus Yam, no stranger to war photography, gives a first-person account from Ukraine.

Expanding the separatist region westward was among Putin’s pretexts for the Feb. 24 invasion, so if such a territorial gain were formalized in political negotiations with Ukrainian leaders, it could be a way for the Russian president to claim a measure of military success.

Despite a Russian failure to seize the Ukrainian capital or unseat Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, a senior Russian general told a briefing in Moscow that the operation’s first phase had been “mainly accomplished.” But Sergei Rudskoi, who heads the general staff’s operational directorate, pointedly refused to rule out an all-out assault on Kyiv or other major Ukrainian cities.

A senior U.S. Defense official, briefing reporters under Pentagon ground rules of anonymity, said indications on the ground matched up with the Russian general’s assertion that the Donbas region was a top priority, with less effort to gain ground elsewhere.

The official said the U.S. assessment is that Russian forces are trying to secure “substantial gains” in Donbas for negotiating leverage, but also to cut off Ukrainian forces in the east.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian government said that it had conducted its first prisoner exchange. Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk, in a message posted to Telegram, said Ukraine received 19 civilians and 10 soldiers and handed back 11 civilians — captured from a sunken ship near Odesa — and 10 soldiers to Russia.

The exchanges came against the backdrop of Ukrainian accusations that Moscow forced hundreds of thousands of residents — including from battered Mariupol — across the border to Russia, adding another layer to the humanitarian catastrophe of Russia’s aggression.

Lyudmyla Denisova, the Ukrainian ombudsman, said more than 400,000 people, nearly a quarter of them children, had been sent to Russia. Denisova accused Russia of wanting to use them as “hostages” in negotiating Kyiv’s surrender.

The Russian government verified the relocations but said they were voluntary and focused on people in Donetsk and Luhansk, eastern regions where pro-Russia separatists have fought in support of Moscow’s invasion.

The developments came as Biden, who attended emergency summits of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the Group of 7 and the European Council in Brussels on Thursday, arrived in Poland to cap off a three-day transatlantic trip focused on the war.

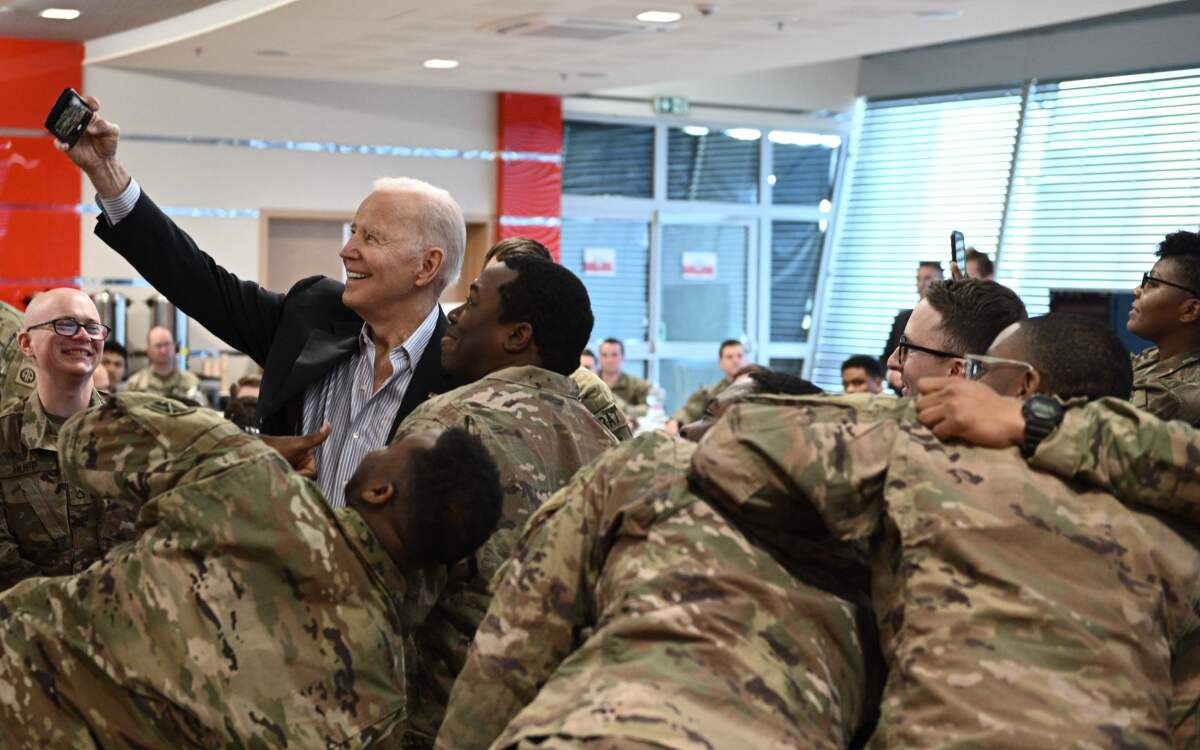

Biden visited Rzeszow, a Polish city near the Ukraine border that has become a hub for weapons going into Ukraine and refugees flowing out, where he gave a pep talk to U.S. soldiers from the 82nd Airborne Division who are stationed in Rzeszow as part of NATO forces.

The president told the troops that more than just a showdown between two nations, the war in Ukraine was part of what he sees as the growing clash between the world’s democracies and its autocracies.

A Holocaust survivor, killed by a missile strike on his apartment, is buried amid the devastation of the war in Ukraine.

“What you’re engaged in is much more than just whether or not you can alleviate the suffering of the people of Ukraine,” he said. “We’re in a new phase. ... We’re at an inflection point.”

He praised Ukraine’s resistance to Russian domination, saying that “the Ukrainian people have a lot of backbone, they’ve got a lot of guts, and I’m sure you’re observing it.”

On Saturday, Biden is scheduled to meet in Warsaw with Polish President Andrzej Duda, and separately greet Ukrainian refugees.

Anatoly Chubais’ resignation as Moscow’s envoy on sustainable development was not the first by a Russian official over the war with Ukraine.

Biden and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen also announced that the U.S. would substantially increase liquefied natural gas sales from the U.S. and other countries to the European Union to help its 27 member nations wean themselves off Russian energy imports.

Speaking in Brussels, Biden said the trade deal would hurt Moscow because Putin has used energy profits to “to drive his war machine.”

The Western push to apply a tighter financial squeeze on the Kremlin, despite dwindling options for doing so, coincides with reports from the Ukrainian government and Western intelligence groups that Ukrainian advances have been pushing Russian troops farther away from Kyiv and stalling the enemy in several other population centers.

“We are going on the counterattack,” Vadym Denysenko, an advisor to the Ukrainian interior minister, said on Ukrainian TV on Friday. “We are moving forward.”

However, in a sign of the challenge of obtaining accurate information on the war, especially in areas where few independent media are present, Ukrainian authorities said they had misidentified a Russian ship destroyed by the Ukrainian military. The ship was the Saratov, not the Orsk, a representative of Ukraine’s armed forces said on Facebook, adding that two other “large landing ships,” the Caesar Kunikov and Novocherkassk, were damaged.

Moscow’s war machine includes a popular TV talk show whose host, Dmitry Kiselyov, takes on anyone who contradicts Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Attacks and shelling have continued in southern and eastern areas, which have been hit hardest since the invasion began.

In the north, a regional official said Friday that Chernihiv was “surrounded” by Russian forces. “The city has been conditionally, operationally surrounded by the enemy,” said Gov. Viacheslav Chaus, speaking on TV and describing regular artillery fire hitting Chernihiv.

In central Ukraine, local officials said Russian missiles hit a military base in Dnipro, though no information on injuries or deaths was given.

In devastated Mariupol, the city council warned that “more and more deaths from starvation” were imminent. The 100,000 residents who remain — out of a prewar population of 430,000 — have little food, water and electricity.

The Times’ Marcus Yam, no stranger to war photography, gives a first-person account from Ukraine.

On Friday, the Ukrainian Defense Ministry acknowledged that Russia was “partially successful” in taking control of enough land around Mariupol to transport supplies and soldiers between Russia and Crimea, the strategic peninsula that Moscow annexed in 2014.

In Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, missile strikes have shaken the city for days and flattened residential areas. The city, which has undergone constant bombardment since the start of the war, lies only about 25 miles south of the Russian border, but has not been taken by Russian forces.

In the Moskovskyi district, east of the city center, plumes of smoke rose in the air Friday, the aftermath of attacks that have destroyed nearly half of the housing. Booms reverberated through the morning as vendors sold packaged sausages from the back of their vehicles and residents lined up at government buildings and churches for aid.

Western Ukraine has remained comparatively free of violence, though the occasional attack has hit suburban and rural regions, including a deadly assault on a military base outside Lviv this month. Still, as Biden visited NATO troops across the Polish border, air-raid sirens sounded in Lviv — a daily occurrence — though no new strikes were reported.

The Russian invasion has killed at least hundreds of civilians and spurred an exodus of more than 3.5 million people. Millions more, half of them children, have been displaced from their homes within Ukraine, according to the United Nations.

On Friday, refugees continued to flee, with hundreds lined up in Shehyni, a Ukrainian town on the Polish border. It was a scene that has been repeated daily for more than a month. Nearly all of those in line were women and children, because most adult men of fighting age are barred from leaving. The refugees carried suitcases, backpacks and duffel bags.

Darya, 27, held her shaggy dog, Lima, in her arms, and was accompanied by her 11-year-old son. She had traveled west across the nation from Dnipropetrovsk, a region in the southeast, and planned to stay with a former classmate who lives in Poland.

“We waited as long as we could, but then the shelling got too close and we decided the safe thing to do was to leave,” said Darya, who declined to give her last name out of concern for her safety. “It’s so difficult, though, to pack up one’s life and leave, not knowing what will happen.”

McDonnell reported from Lviv and Shehyni, Yam from Kharkiv, Kaleem from London and King from Washington. Times staff writer Noah Bierman in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.