Hindu nationalism is a threat to Muslims and India’s status as the world’s largest democracy

- Share via

GULAOTHI, India — Nasir Ali was selling tennis shoes in this small town east of New Delhi when a dozen men surrounded his street stall.

He instantly recognized them as the local goons: members of the Bajrang Dal, a Hindu nationalist group with a long history of violence and a rising profile.

They accused the 28-year-old Ali of insulting their faith, because one of the brands he carried was Thakur, which is also the name of a prominent Hindu caste. A rival shoe seller had tipped them off.

“How can you sell shoes with Thakur written on them when you are a Muslim?” one of the men shouted.

Ali explained that he meant no disrespect, that he didn’t create the brand, he just sold it.

Then the men called the police, who booked Ali for provoking unrest. He spent the next two days in jail, where he said he was beaten by officers in the presence of Bajrang Dal members.

“I was targeted because of my religion,” he said. “I live in fear that anyone can beat me up and there’s nothing I can do. It makes you feel helpless.”

Fueled by Hindu nationalism, encouraged by authorities and carried out with impunity, oppression of Muslims has become so pervasive in India that experts said it is undermining the country’s standing as the world’s largest democracy and raising doubts about its future as a secular state.

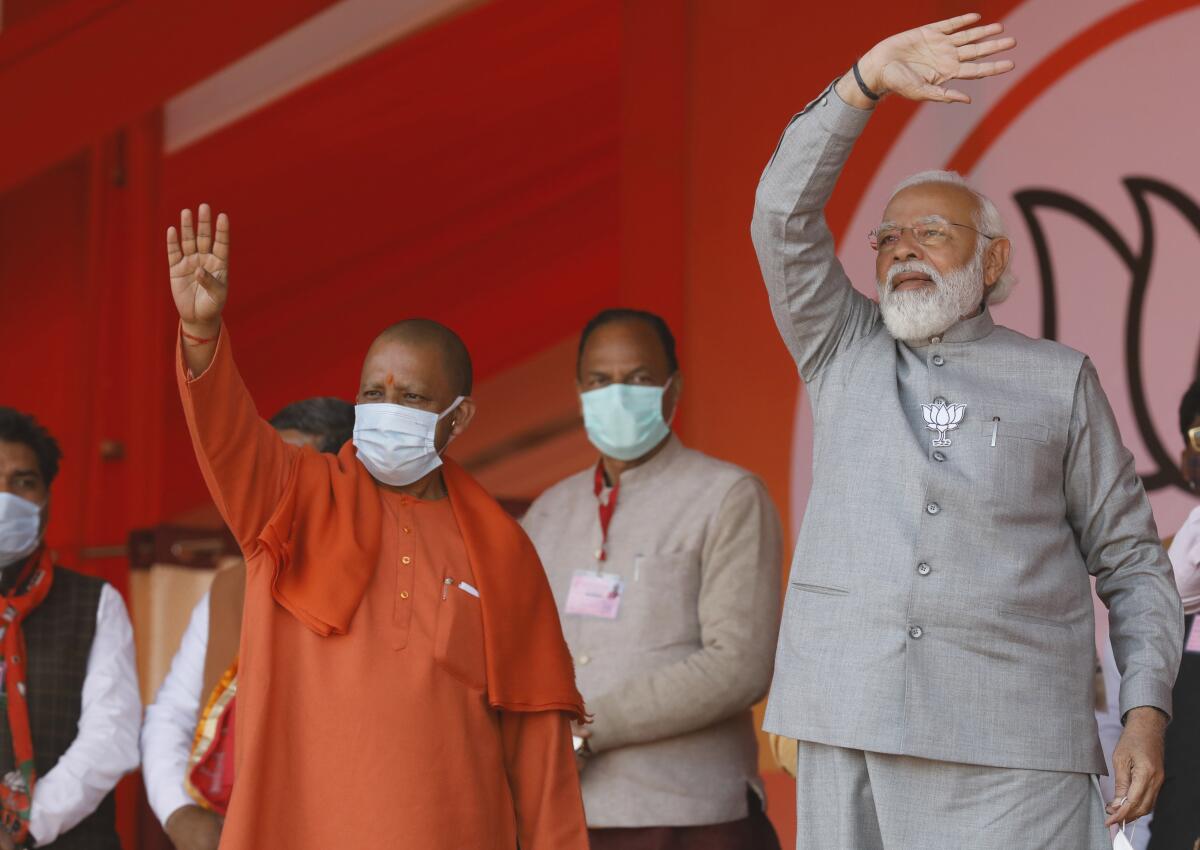

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, have long fanned anti-Muslim sentiment as part of a winning strategy to galvanize support from Hindus, who make up 80% of India’s 1.4 billion people.

But the violence and harassment have intensified in the run-up to assembly elections in five states this month and next. A decisive victory in the party’s stronghold of Uttar Pradesh could signal the continued political viability of Hindu nationalism and bolster Modi’s chances of winning a third term in 2024.

“The BJP has sent a message that it’s OK to go after Muslims,” said Aakar Patel, chair of Amnesty International India. “This is what makes them popular. This is why we’re seeing attacks and persecution on a wholesale level.”

As nationalists have amplified their calls for India to rewrite its constitution and forge a Hindu nation-state, mob rule has taken hold.

This month in the southwestern state of Karnataka, after Hindu nationalists hounded Muslim schoolgirls for wearing Islamic head scarves, authorities deemed the threat of violence serious enough to warrant shutting down schools and colleges for several days.

More disturbingly, radical Hindu leaders have reportedly called for the slaughter of millions of Muslims, with one extremist invoking ethnic cleansing in Myanmar.

“Either you prepare to die now, or get ready to kill, there’s no other way,” Swami Prabodhanand Giri, president of the far-right organization Hindu Raksha Sena, told supporters at a religious gathering in December. “This is why, like in Myanmar, the police here, the politicians here, the army and every Hindu must pick up weapons because we have to conduct this cleanse.”

::

The roots of India’s modern religious strife can be traced to 1947 when Britain — under pressure from Muslim political leaders who wanted a Muslim-majority state — redrew the borders of its colony.

Out of that partition of the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan was born. But because the new boundaries were drawn so hastily, it left many Muslims and Hindus on the wrong side of the border, unleashing a wave of violence and terror that killed 1 million people and displaced 14 million more.

Still, millions of Muslims stayed for India’s formation as an independent state, whose first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, suppressed Hindu nationalism in favor of a more egalitarian vision for the country.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that secularism began to erode. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her successor — her son Rajiv — began pandering to various conservative religious groups, setting the stage for the BJP to exploit religious tensions.

Life for Muslims would continue to deteriorate. A landmark 2006 study commissioned by the formerly dominant Congress Party found that Muslims suffered far higher rates of poverty than Hindus while lagging behind in literacy, employment and access to banking.

Attempts to act on the findings and deliver social programs to Muslims have stalled. One petition filed in the Supreme Court argued the report infringed on the rights of Hindus.

“If you ask most people today about secularism in India, many of them will tell you it’s a thing of the past,” said Gilles Verniers, a political scientist at Ashoka University just north of New Delhi.

“It’s an idea that has been rejected and become synonymous with the idea of an appeasement of minorities, which of course is not what the term was meant to mean in the first place,” he said. “The meaning has been transformed into a weapon that can be used against minorities in order to prevent them from expressing publicly their religious belonging.”

The struggle highlights the fragility of India’s healthcare system as another wave of the coronavirus fueled by the Omicron variant gathers momentum.

Modi has long understood the power of intolerance as a political strategy. In 2005, when he was the leader of the state of Gujarat, he was barred from entering the United States for failing to stop deadly riots by Hindus against Muslims.

Since he took office in 2014, his party winning in a landslide, he has presided over a democracy in decline. The Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index lowered India’s ranking to 46th from 27th, while the Washington-based Freedom House downgraded the country to “partly free” from “free.”

In a 2020 report to Congress, the U.S. State Department offered a grim assessment of India’s human rights record, listing a litany of abuses that included extrajudicial killings, torture and arbitrary arrests.

The backslide complicates the Biden administration’s approach to India, which it needs as a democratic counterweight to China and a security partner in the region now that U.S. forces have left Afghanistan.

President Biden has nominated a close political ally — Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti — to be the U.S. ambassador there.

Although democracies everywhere have faced setbacks in recent years — most notably the U.S. — experts said India’s situation reaches far beyond its borders.

“The fate of the world’s liberal democratic order is closely tied to India because of its sheer size as the world’s largest democracy,” said Niranjan Sahoo, a senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, a global think tank in New Delhi. “It’s precisely because of this and the potential to counterbalance China’s authoritarianism that the U.S. has invested so much in India.”

India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, rejected appraisals of India’s democratic decline, redirecting criticism at the U.S. and attempts by President Trump and his allies to overturn the 2020 election.

“You use the dichotomy of democracy and autocracy,” Jaishankar said last year. “You want the truthful answer? It is hypocrisy.”

::

Contrary to the headlines, moderate views persist in India. A Pew Research survey last year found 85% of Hindus agreed that respect for all religions was important to being truly Indian.

Yet their voices are often drowned out by right-wing nationalists.

Religious persecution has not been limited to Muslims. Mobs have burned effigies of Santa Claus and crashed Christian services, and nationalists have called for the massacre of Sikhs because of their prevalence in farm protests last year that forced Modi to scrap one of his signature policy initiatives, agricultural reform.

In December, a mob of Hindu nationalists stormed a Catholic school to prevent what they thought was a religious conversion ceremony in the central state of Madhya Pradesh.

But at 13% of the population, Muslims have been the most common targets.

In a new strategy to hurt Muslims, nationalist groups and Hindu religious leaders have advocated boycotting their businesses.

A video that was shot last month in the central state of Chhattisgarh and shared widely showed villagers pledging to never buy goods from Muslims or rent or sell land to them.

The annual tribute to India’s oppressed castes remains marred by the violence that broke out four years ago.

Nowhere has the persecution of Muslims been more vicious than in Uttar Pradesh, the most populous state in India and also one of its most impoverished.

The state is led by Yogi Adityanath, a right-wing nationalist Hindu monk considered a potential successor to Modi. Last month he described state elections as a lopsided communal contest between the “80” and the “20” — an allusion to the state’s respective population breakdowns for Hindus and Muslims.

Some of the violence against Muslims there has been high-profile. In May, an 18-year-old vegetable seller named Faisal Hussain was reportedly beaten to death by three police officers for violating COVID-19 restrictions.

“There were a lot of others selling vegetables,” said his sister, Khushnuma Hussain, 25. “Why did the police single him out? Would he be dead if he was Hindu?”

Three months later, a Muslim rickshaw driver was beaten and paraded in front of a mob chanting “Jai Shri Ram,” a nationalist mantra praising a Hindu god. Video of the attack went viral, showing the driver’s young daughter clinging to her father and begging the crowd to stop.

Then later that month, a Muslim dosa vendor was assailed after he was accused of concealing his religion to Hindu customers.

“His stall should have had a Muslim name. I was misled,” said Rajesh Mani Tripathi, who was part of the Hindu crowd that heckled the vendor. “Why are Muslims still here? They should go to Pakistan.”

Then there are incidents that have become so commonplace that they have simply become part of the fabric of daily life — like the case of Ali.

After his release from jail, he went into hiding and lived with relatives for fear of retribution by police and Hindu vigilantes.

“I didn’t speak to anyone,” he said. “I hardly got out of the house for two months.”

When Ali was arrested, his shoe business was still new.

He started it because his old job selling vegetables from a cart became untenable amid fears that Muslims were spreading the coronavirus. Hindu neighborhoods, where he made most of his money, would no longer let him in.

Even though the shoe business had doubled his income, Ali felt he had no choice but to shut it down. Reopening would almost certainly bring retaliation.

With money dwindling, and two young children to feed, he went back to selling vegetables.

Each day, he wakes up early and pushes his cart from village to village, swallowing his fear whenever he arrives in a Hindu community.

Special correspondent Parth M.N. reported from Gulaothi and Times staff writer Pierson from Singapore.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.