Amid a crackdown, Afghan refugees in Iran fear the ‘unthinkable’: Being sent back

- Share via

TEHRAN — Unlike most of his compatriots, Jamal Papoli didn’t have to worry about being stuck in Afghanistan when the Taliban sped to power in August. Papoli had quit his homeland years ago to set up shop as a stonemason here in neighboring Iran, just outside Tehran.

But instead of relief, what the 30-year-old father of two feels these days is fear. As one of hundreds of thousands of undocumented Afghans in this country, he’s frightened of getting snared in one of the growing number of sweeps by Iranian authorities and sent back to his native land, where an uncertain fate awaits — especially for him as an ethnic Uzbek in a Pashtun-dominated, Taliban-run society.

After all the previous times Papoli was arrested and deported, he simply waited until he could sneak back in again. But Afghanistan’s new regime and Iran’s intensifying efforts to tighten the border mean that that’s not a viable option anymore.

“It’s no longer like it was in the past. If I get caught again, I would be given to Taliban forces at the border crossing” — an “unthinkable” outcome, Papoli said. “I’ve already gotten my wife and two children smuggled into Turkey.

“I have no option but to earn some money and get out of here myself. … I would rather die en route to Germany than get deported to the Taliban.”

Papoli’s plight offers another twist on the prevailing political realities since the Taliban’s surprise return to governing Afghanistan, 20 years after the radical group’s first attempt at it from 1996 to 2001. As countless residents continue to seek ways to flee the country, many of the more than 3 million Afghans who have already found safer haven in Iran are grappling with the fear of being shipped back by a government in Tehran that finds their presence increasingly burdensome.

That, in turn, could become a headache for the West, particularly Europe, if large numbers of refugees in Iran feel threatened enough to strike out for other nations. Human smugglers report a jump in demand for their services in helping people migrate farther west.

Several thousand Afghans continue to make their way across the border into Iran every day, even though the Iranian economy is in a tailspin because of crippling U.S. sanctions. Since Kabul fell to the Taliban in mid-August, 400,000 Afghans are estimated to have streamed into the Islamic Republic, often negotiating vertiginous mountain passes and other treacherous terrain to escape Afghanistan’s new-old rulers, its racking poverty or both.

That figure is three times the number of Afghans whom U.S. and other NATO nations’ forces airlifted out of Kabul in the chaotic days after the Taliban seized control of the capital. Indeed, Iran currently hosts the equivalent of 10% of Afghanistan’s entire population.

“Now that many Afghans see the dream of returning home gone for good, thousands of them have pinned their hopes to better living conditions in Iran,” said Abbas Hosseini, a veteran Afghan journalist who is the director of the Tehran-based AVA news agency.

The countries lying closest to Afghanistan have competing agendas in the new Taliban era.

The great majority of the refugees here are members of the Tajik, Uzbek or Hazara ethnic minorities, who are routinely discriminated against — or worse — at home. Hazaras in particular, as Shiite rather than Sunni Muslims, are despised by Afghanistan’s ruling Pashtuns; they have long been the targets of mass killings and other atrocities, which have continued under the Taliban, rights groups allege, despite the new rulers’ smiling pledges of a tolerant pluralism.

Zabih, a young Hazara man who gave only his first name, recalled the clenching fear that overtook him recently as he tried to elude authorities who, he thought, would deliver him to certain oppression or even death in Afghanistan if they laid hold of him.

“I was screaming at the top of my lungs and running like a sprinter for my life that night. … I was jumping over fence after fence and rolling down muddy, steep hills in the dark, hoping the chasing officers would give up,” said Zabih, who has been living in one of Iran’s northern cities.

Like Papoli, Zabih has been caught and expelled from Iran several times before, and has always managed to steal back in.

“But having heard the stories and rumors about what the Taliban has been doing to Hazaras and Tajiks, I couldn’t risk being easily busted this time and sent back,” he said.

Afghans eager to escape persecution, poverty or persistent conflict have taken flight to Iran for decades; shantytowns full of refugees line the outskirts of Tehran and cities such as Mashhad and Isfahan. About 850,000 of the more than 3 million migrants are undocumented, Hosseini said.

Every day, hundreds more arrive overnight, often getting dumped by smugglers in Tehran’s famous Azadi Square and left to fend for themselves. Hosseini said that smugglers’ fees have quadrupled, to about $500 to $600 per person, as Iranian authorities have stepped up patrols of the 560-mile border with Afghanistan.

This year, Iran had sent back 1.15 million Afghan migrants by Nov. 28 — a 47% increase over the same period last year, according to the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration. The government, led by newly elected hard-line President Ebrahim Raisi, is in talks with the Taliban on strengthening controls at the border.

Human Rights Watch says the Taliban has killed or ‘disappeared’ more than 100 former Afghan police and intelligence officers since taking power.

The Afghan Embassy in Tehran is no help for its citizens who have made it through: The pre-Taliban ambassador left the country immediately after the fall of Kabul.

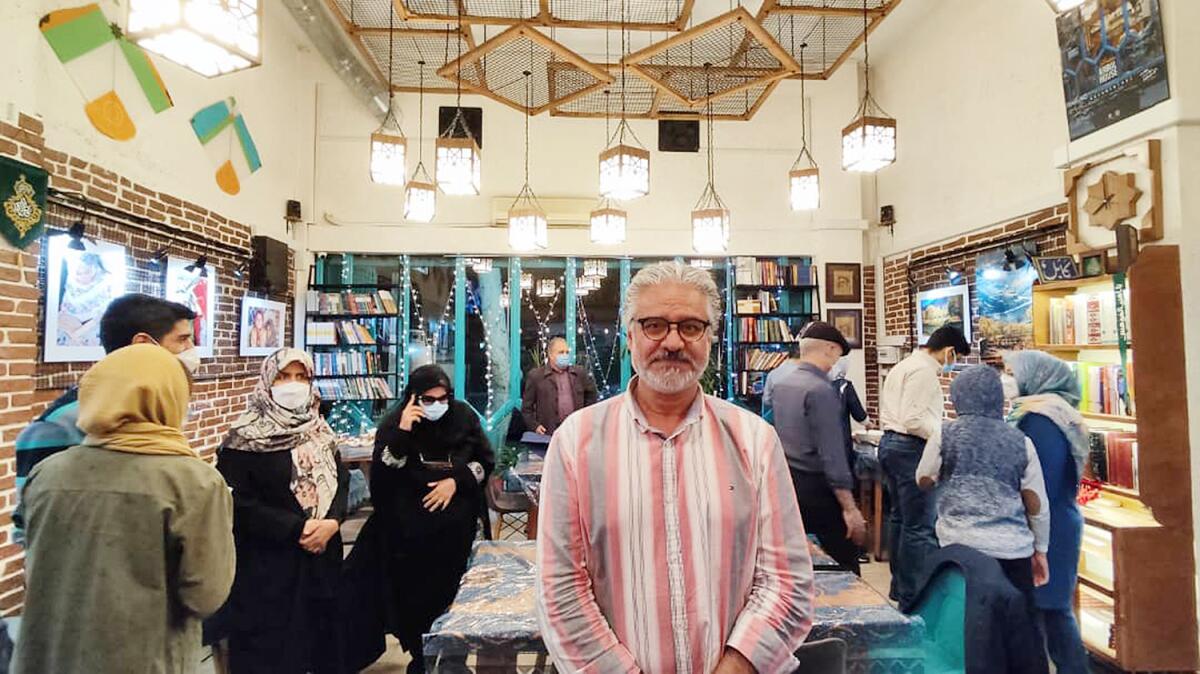

Mohammad Musa Akbari, a veteran Afghan photographer and longtime resident in Iran, is trying to fill the gap. He’s turned his cozy restaurant in busy downtown Tehran, Khaneh Kabul (House of Kabul), into a gathering place that serves up Afghan food and cultural events for the homesick, and assistance for those in need, including children unable to afford books and school supplies.

Akbari’s three children were born, raised and educated in Iran, but have no path to Iranian citizenship under current laws. His daughter is married to an Iranian social activist who has taken up the refugees’ cause.

At the same time, Akbari doesn’t think Iran can afford to host any more of his former compatriots. He blamed false warnings of mass displacement or ethnic cleansing in Afghanistan for the latest wave of immigration, even though human rights groups have reported recent killings of Hazaras.

“Many rumors are circulating,” Akbari said. Recently, “I raised $5,000 to $6,000 and personally went to Afghanistan to help. But there are unknown sources who are spreading these baseless rumors.

“Iran cannot take in more refugees,” Akbari said. “This is a fact.”

Abdolhakim Mahdi would be perfectly happy for another Afghan to take his place in Iran. The 22-year-old is here legally on a temporary visa and, like many other immigrants who hold documents, was able to commute freely between Iran and Afghanistan when the U.S.-backed government still held sway in Kabul.

Now, with the Taliban in power and Iranian authorities deporting more Afghan migrants, who risk punishment by the new regime, Mahdi’s dream is no longer to return to his homeland after getting a degree; safety and opportunity lie elsewhere.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s absolutely out of the question now to go back to Afghanistan under the rule of the Taliban,” he said. “I’m desperately applying to universities everywhere.”

He’s been waiting in long lines outside the German Embassy in central Tehran. Video posted on social media show similar scenes outside the diplomatic missions of other nations.

“Everybody is on the move now,” Mahdi said.

Special correspondent Khazani reported from Tehran. Staff writer Chu is based in London.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.