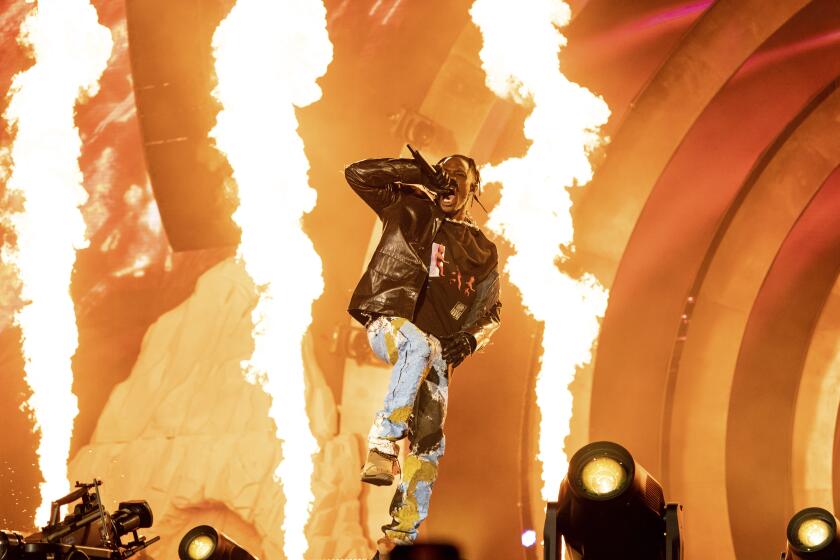

Travis Scott sought to uplift Houston. Did he let it down?

- Share via

HOUSTON — Playwright ShaWanna Renee Rivon was speaking at her alma mater — the University of Houston — a few months ago when a student told her he wouldn’t be able to attend her upcoming writing workshop: He was going to Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival.

“He was expecting something historical. I saw it on his face. It was just a sense of pride,” Rivon said.

When news broke that the Nov. 5 concert had turned deadly, ultimately claiming nine lives, Rivon scrambled to check on the student. He survived, she said, but was shaken. So were many Houstonians who had taken pride in Scott and his re-imagining of the Space City’s urban theme park that once stood next to the Astrodome and shaped childhoods across race and class lines.

AstroWorld was razed in 2006, when Scott — born Jacques Bermon Webster II — was 15 years old. But its memory loomed large for him and other Houstonians. In a nostalgic nod, he titled his 2018 album “Astroworld” and launched his two-day music festival of the same name at the theme park’s former site the same year, making the entrance gate a cross between his image and one of the iconic rides, the Texas Cyclone.

The roughly hundred-acre park opened in 1968 beside the Interstate 610 loop encircling downtown. Rides included the Texas Cyclone — a wooden roller coaster modeled on New York’s Coney Island Cyclone — and Thunder River, considered the world’s first river-rapids ride when it opened in 1980. It grew to include a water park and dance club, Studio A, that broadcast a show on local television, “Videocity.”

“When you got to a certain age, in the summer, we would get a summer pass. Your parents would take you up there and it was just a place to be,” said Rivon, 43, who recalled dancing at the club. “It was just a sense of freedom.”

The park’s Southern Star Amphitheatre hosted performers including the Beach Boys, the Grateful Dead and AC/DC, introducing many Houston youths — in an era before the internet and streaming music — to genres they’d never heard, said John Chiles, an adjunct professor in the University of Houston’s African American studies program.

Houston is a city carved into neighborhoods, from the mansions of River Oaks and Rice Village to the low-income apartments of Greenspoint and Sharpstown. It was also originally divided into wards, which often correlated with ethnic communities. The Fifth Ward was Latino; the Third Ward — where Scott’s grandmother lived and which he often references in his songs — was historically Black.

For many, AstroWorld transcended those divisions, Chiles said. Houstonians didn’t just grow up attending the theme park, which was eventually subsumed by Six Flags, he said; they worked there, often alongside people from totally different parts of town.

“AstroWorld is really woven into the Houston community,” said Chiles, 58.

After the deadly crowd crush at the festival during Scott’s set, Chiles said, “the citizens of Houston are heartbroken.”

“It goes back to AstroWorld being a positive experience for so many,” he said.

Chiles said Houstonians are not just following the unfolding investigation, led by police, but also “taking it personally.”

“There’s a great pride here, especially in the hip-hop community,” said Chiles, who teaches about Houston hip-hop legends, inviting local artists to speak to his class.

Beyoncé grew up in the Third Ward and name checks it in her songs like Scott does (he’s also been known to visit Frenchy’s Chicken and Shipley Do-Nuts, bringing girlfriend Kylie Jenner, who posted about the doughnuts on Instagram). Megan Thee Stallion also grew up in Houston and is expected to graduate next month from Chiles’ alma mater in the Third Ward, Texas Southern University, a historically Black school. But neither of them created a music festival the size of Astroworld, which debuted in 2018, returned in 2019, then was postponed last year due to the pandemic.

Unlike other “pop superstars,” Scott used his music, and the Astroworld Festival in particular, to attract artists of other genres to Houston, Chiles said: In addition to hip-hop standbys like Drake and Young Thug, this year’s lineup included Bad Bunny; Tame Impala; Earth, Wind & Fire; and SZA. Locals also noticed Scott giving back in other ways, to charities and especially youth, Chiles said. Mayor Sylvester Turner gave Scott a key to the city a year after his first Astroworld Festival.

“People that know Travis Scott know he’s a good person. He does a lot of things here quietly,” Chiles said, noting Scott joined his grandmother to dedicate one of eight Houston public school gardens his foundation helped build days before Astroworld.

Chiles, who has met Houston Police Chief Troy Finner, said he “came up from the ranks; he cares.” But he was troubled to see Finner and other officials blame Scott for not shutting down the concert (Finner stressed at a Wednesday briefing that Scott had the authority to stop the show).

“We have to look at the crowd’s willingness to be managed,” Chiles said. “This happened in Houston, but this is not a Houston issue.”

Many of Houston‘s hip-hop stars, including Paul Wall and Slim Thug, have been silent since the Astroworld disaster. Rapper Bun B, also known as Bernard Freeman, 48, went on Instagram Live from Houston on Monday to talk about the tragedy.

Houston Police Chief Troy Finner said there was no need to hand over the criminal investigation to an outside agency.

“The city dealing with a lot,” he said. “I wasn’t even there and I feel a certain way … extremely emotional about the situation.”

Bun B said his loved ones who were at the festival were safe, but he noted how much trauma everyone involved experienced. He said he flew from Houston to Los Angeles last weekend for ComplexCon with concertgoers who were returning to California after attending Astroworld, and one youth seemed particularly traumatized, wearing headphones in the plane, “trying to process it through Travis Scott’s music, which was his whole reason for going.”

“What are we not getting to as a community with this? We sent our children, and I mean collectively, from around the world,” Bun B said.

Houston disc jockey Michael Pierangeli, who attended all three Astroworld festivals, said the crowd was more intense this year.

“The anticipation was obviously higher because we’re in the middle of a pandemic, this is the first big event outside and it’s Travis Scott. You’ve got a lot of people flying in from all over,” said Pierangeli, 30.

Houston attorney Tony Buzbee, a former Republican mayoral candidate and River Oaks resident, grew up going to the AstroWorld park.

“There is that nostalgia,” Buzbee said. “Most of the people who went to that concert don’t know what AstroWorld was, but the people who run the city do.”

Buzbee said he let his teenage sons attend the festival in 2019, but they felt unsafe and didn’t return. Buzbee represents the family of one of those killed this month, 21-year-old Axel Acosta, and said they hold both the organizers and Scott responsible.

A 22-year-old college student who was critically injured at the Astroworld Festival in Houston has died.

“You can’t encourage people to riot. You can’t do those things as a responsible person, no matter how popular you are, no matter if you’re the genesis for it, no matter if the mayor gave you the key to the city and they stop traffic to give you a special place to park your Lamborghini,” Buzbee said. “Did he go to an after-party after this concert? I’m going to ask him when I depose him.”

Houston, the fourth-largest city in the U.S., is also considered by many the most diverse. That was reflected in the Astroworld crowd and the casualties, which included Black, white, Latino and Indian American attendees, ages 14 to 27.

Among them was Bharti Shahani, 22, whose parents had emigrated from India, settled in Houston, opened a clothing store and sent her to Texas A&M University.

“Houston is a diverse community of immigrants, people who are seeking better opportunities for the next generations,” said one of the Shahanis’ attorneys, Mohammed Nabulsi, as he stood beside them at a Thursday briefing. “Bharti played the role that first-generation oldest siblings play: They are the glue of the family, they are the liaisons, the mentors…. This is what not just the Shahani family has lost, but what our whole community has lost: a bright star.”

Lawyer James Lassiter, whose firm is representing the family, recalled going to AstroWorld as a child, how the park had “always been a symbol of family and all the good things about Houston.”

Lassiter said his 17-year-old son was also at the festival, and “I was blessed that he made it home that night.”

Ezra Blount, a 9-year-old who attended Astroworld with his father, remained in critical condition at a Houston hospital Friday after being trampled during the crush, said his grandmother Tericia Blount, who lives in the Houston suburbs.

Music festival goers recount the chaos of that day, when eight people died, two dozen were hospitalized and scores more were injured.

Blount, 52, a retired nurse, was at Texas Children’s Hospital, where she said doctors were trying to wean Ezra off medications that had kept him in a coma for a week as they addressed swelling in his brain and heart issues.

She said her son had taken Ezra to Astroworld because Scott billed it as a family event.

“He had face painting for the children, Ferris wheels and rides,” she said. “It was said it was a family event for all ages. So you would think we can all go, him and his son, bonding. And then your whole world is just totally capsized.”

Blount said the family, who have retained attorney Ben Crump, want to see everyone involved held accountable, including Scott.

“He could have stopped,” Blount said. “He saw things, but he just kept going.”

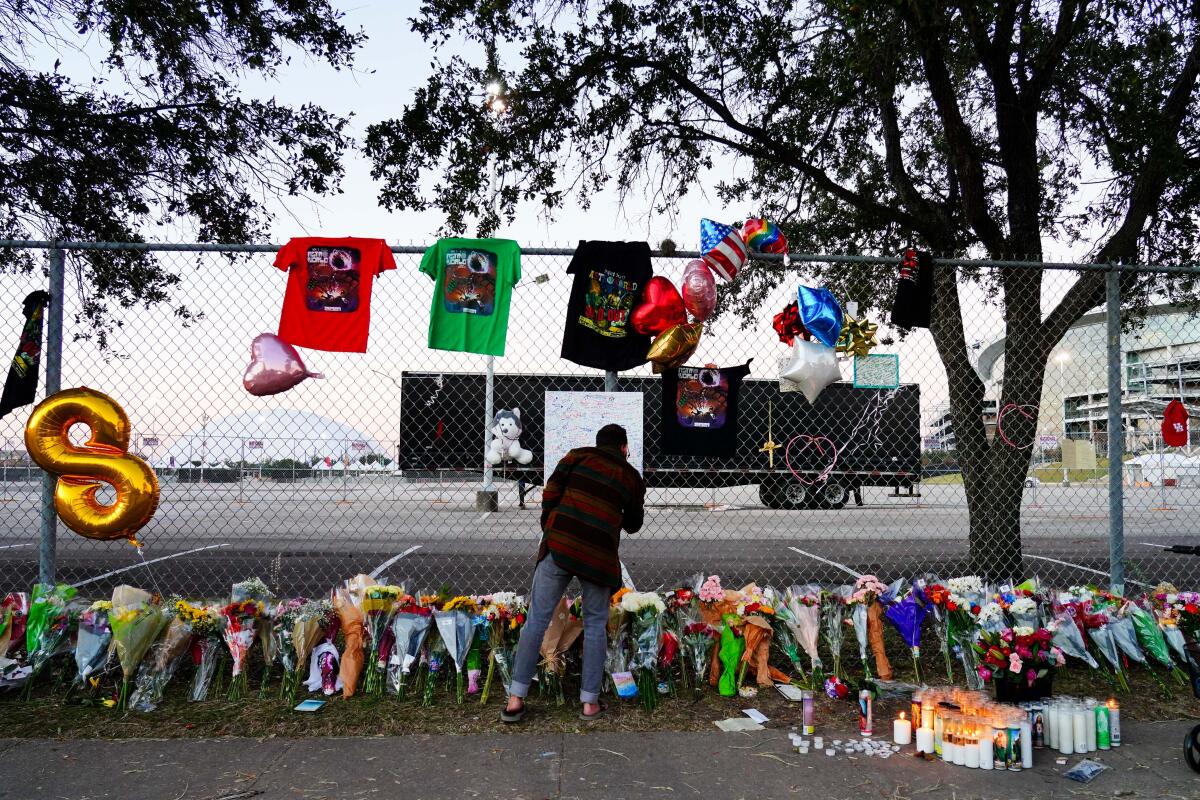

By Friday night, a week after the concert, a memorial at the Astroworld Festival fence had grown to include photographs of the dead, cards, balloons and hundreds of bouquets.

At dusk, Toni Tacorda was the only visitor. The University of Houston student said she had worked security at the concert and came to pay respects on behalf of her security team, who live across the state. She said one of them, an 18-year-old, had extricated the body of the 14-year-old concertgoer who died.

“We could only save so many people,” said Tacorda, 21. “We were doing our jobs.”

Tacorda moved to Houston from the Philippines at age 6 and considered it a welcoming place. She was heartened to see that the memorial had grown as people added tributes.

“That’s the thing about my city: There’s always somebody there for you,” she said.

She attended the last two Astroworld concerts and was inspired by Scott’s rise, but she didn’t think he could salvage the festival from such a tragedy.

“Astroworld is not going to happen again,” she said. “It’s going to be another disaster associated with Houston.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.