After jailing rivals, Nicaraguan president poised for reelection

- Share via

Dolly Mora’s hopes for fair presidential elections in Nicaragua quickly evaporated during the summer when, one by one, potential challengers to longtime President Daniel Ortega were arrested under a new treason law. Police also detained two of her friends, opposition activists still behind bars.

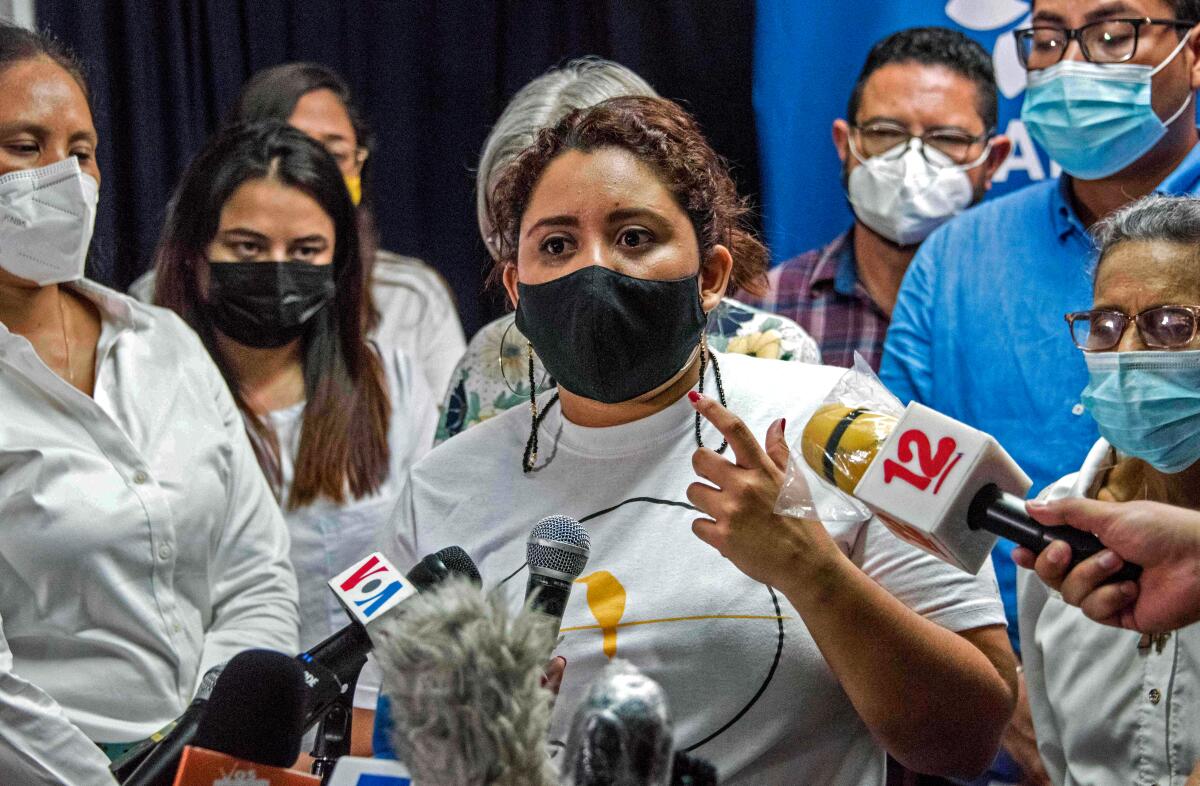

The 29-year-old leader of the Nicaraguan University Alliance, a political youth movement, does not plan to vote in Sunday’s election, which will see five lesser-known candidates competing against Ortega instead of the seven who are behind bars or under house arrest. She has spent recent days promoting #MiCandidatoEstaPreso, or “my candidate is incarcerated,” on social media.

“We don’t think there’s anything else to do,” Mora said in an interview from the Central American country, preferring not to disclose her location. “Ortega has completely buried this process. There’s no possibility for citizens to participate and decide.”

Ortega, 75, is poised to continue to maintain control over the nation in an election that has been denounced as illegitimate by the United States and human rights groups. Experts expect that his reelection will thrust the country into deeper international isolation, worsen its economic crisis and swell its soaring number of refugees.

“They are deeply compromised in that all the major opposition leaders are in jail,” said Cynthia Arnson, the director of the Latin American Program at the Wilson Center. “It’s hard to even call these elections.”

The first major election day following a year of relentless attacks on voting rights and election officials went off largely without a hitch.

The Sandinista government of Ortega, a former Marxist guerrilla who has served as president continuously since 2007, has passed laws that stifle free speech, arrested journalists and civic leaders, and quelled political dissent. Many have been arrested under a 2020 law that defines “traitors” in sweeping terms to include people who “undermine independence, sovereignty and self-determination.”

The repression has continued despite targeted sanctions from Washington and the European Union on Ortega’s allies and family, as well as condemnation from the Organization of American States (OAS), a regional body. On Wednesday, the U.S. Congress passed the Renacer Act, which calls to review whether Nicaragua should be allowed to remain in the Central America Free Trade Agreement.

Ortega has justified the wave of arrests by saying that those detained are “criminals who have conspired against the safety of the country.” In a meeting of the OAS in recent days, a Nicaraguan official accused the country’s critics of being “coup leaders” and of trying to “destabilize national sovereignty.”

Ortega first rose to power after overthrowing U.S.-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979 with other Sandinista revolutionaries. He served as president in the 1980s before his party, the Sandinista National Liberation Front, suffered a stunning defeat in 1990.

Since returning to the presidency, Ortega has served alongside his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, with a “creeping authoritarianism,” said Hilary Francis, a historian of Nicaragua at Northumbria University in England.

In 2014, his party, which has the support of the military, pushed through a constitutional amendment that allowed Ortega to run for reelection indefinitely. In 2018, a crackdown by national police and pro-government armed groups against large protests left more than 300 people dead.

Apart from the 2020 law that defines “traitors” in general terms, other recent laws that have been criticized for impeding fair elections include one that requires people who receive funding or “objects of value” from abroad to register as “foreign agents” and abstain from running for office, and another that criminalizes the dissemination of “false” information that produces “alarm, fear and distress in the population.”

Meanwhile, Ortega’s family and allies have amassed substantial control of the country’s media landscape, gaining ownership or management of TV channels, radio stations and online news sites, according to a Reuters report. On Monday, Facebook announced that it had removed more than 1,000 Facebook and Instagram accounts with fake profiles that it said were run by the Nicaraguan government and its ruling party to manipulate public discourse.

“There has been an entire legal framework designed to [attack] democracy,” said Manuel Orozco, an expert on Nicaragua at the Washington, D.C.-based think tank Inter-American Dialogue who was accused in a Nicaraguan judicial complaint this summer of conspiring against the country with opposition leaders. “People are afraid of speaking out, of demonstrating in the street, because they will be detained.”

Critics have accused Ortega’s government of holding arrestees without revealing their whereabouts or providing them with access to attorneys or their family. The repression has sent journalists, activists and academics fleeing — often to the U.S. and neighboring Costa Rica.

The incarceration of sports journalist Miguel Mendoza in June citing the 2020 sweeping treason law provoked widespread fear, said journalist Alberto Miranda, who fled in July. Many colleagues have resigned.

“We know we are under a dictatorship, there aren’t constitutional guarantees,” he said. “There’s no electoral process. It’s simply a circus.”

The seven potential presidential candidates arrested include Cristiana Chamorro, the daughter of former President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, who was accused of money laundering and placed under house arrest. Police have also detained business executives and former Sandinista guerrilla leaders who fought alongside Ortega during the revolution.

Mónica Baltodano, a former Sandinista guerrilla commander who joined the movement at age 15, said that after seeing several leaders arrested, “We realized that there wasn’t any limit to the regime, that they could capture us and disappear us.”

Baltodano, who fled to Costa Rica with her husband and daughter during the summer, said that Ortega’s ideals have broken sharply with those that had motivated the revolutionaries. She claims his government is “not even a dictatorship of the left,” pointing to how he supported a ban on abortion before the 2006 presidential elections.

“We fought for freedom, for social justice, for democracy, because Somoza didn’t allow free elections,” she said. “The [party] of Ortega doesn’t fight for those ideals, it only uses its rhetoric.”

Orozco, from the Inter-American Dialogue, said that he expects the election will result in a drop in foreign investment in Nicaragua and increase migration, pointing to how the number of Nicaraguans apprehended at the U.S. border jumped sharply in the weeks following the wave of summer arrests. Using remittance data, he’s estimated that about 200,000 Nicaraguans have fled the country since the 2018 protests.

Tanya Mroczek-Amador, who runs a relief center for refugees by Nicaragua’s border with Costa Rica, said that she’s seen many more child refugees since June. They’ve said they’re joining parents who left earlier and are asking for their family “to go ahead and come because they just see no future in Nicaragua,” she said.

Analysts expect the election will provoke stronger action from the international community. Ryan Berg, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, pointed to how the OAS could vote to suspend Nicaragua from its body.

“There’s a sense among countries that are willing to act on Nicaragua — the EU, Canada, the U.S. — that something more needs to be done,” he said.

Elvira Cuadra, a Nicaraguan sociologist in Costa Rica, said that tensions between opposition movements that emerged in 2018 and established parties made it difficult for the opposition to find unity. Opposition leaders say that they need to find a strategy that takes into account how much of the opposition is dispersed outside the country.

“The first thing we need is an honest dialogue that permits that all opposition in Nicaragua to find common cause and act in a much more coordinated manner,” said Jesús Tefel, 35, a businessman who used to help lead Blue and White National Unity, a Nicaraguan opposition movement, and has fled Nicaragua with his wife and 10-year-old son.

Since the 2018 protests, Mora, the youth activist, has been trying to lie low, moving every few months to protect herself from retaliation. The weekend before the arrest of her friends Max Jerez and Lesther Alemán, there was a police presence outside the home she shared with Jerez and another activist.

They prepared to be arrested, calling their families. On the night of July 5, sirens began to sound and officials stormed in.

Jerez and Alemán — like the presidential hopefuls — were accused under the treason law.

Friends have urged Mora to leave the country but she has decided to stay, even if it means being caught and jailed, saying that the 2018 protests had shown her “this generation had a clear commitment” to change the country.

“Unfortunately, it happened,” she said. “We have two friends in jail and we’re not going to go.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.