U.N. experts recommend malaria shot for use in children across Africa

- Share via

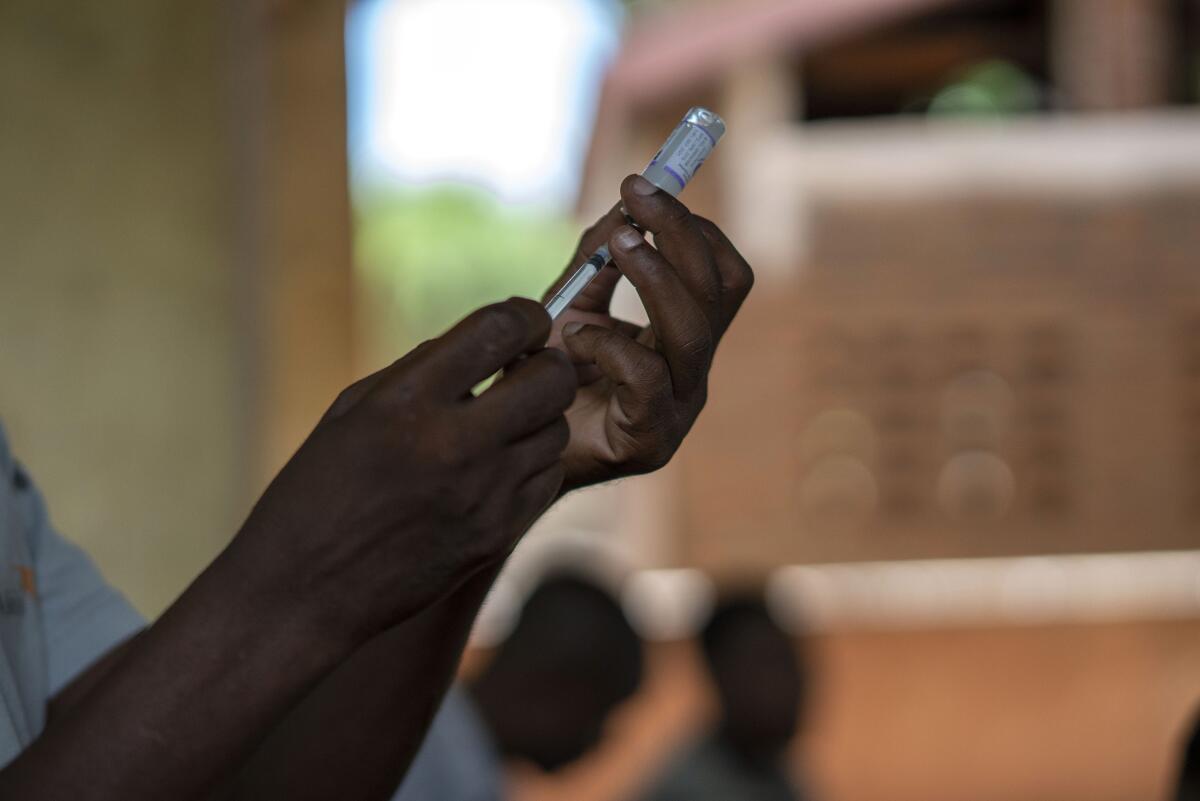

LONDON — The World Health Organization on Wednesday endorsed the world’s first malaria vaccine and said it should be given to children across Africa in the hope that it will spur stalled efforts to curb the spread of the parasitic disease.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called it “a historic moment” after a meeting in which two of the U.N. health agency’s expert advisory groups recommended the step.

“Today’s recommendation offers a glimmer of hope for the continent, which shoulders the heaviest burden of the disease. And we expect many more African children to be protected from malaria and grow into healthy adults,” said Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the WHO’s Africa director.

The WHO said its decision was based on results from ongoing research in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi that has tracked more than 800,000 children who have received the vaccine since 2019.

The malaria vaccine known as Mosquirix was developed by GlaxoSmithKline in 1987. Though it’s the first to be authorized, it does face challenges: It is only about 30% effective, it requires up to four doses, and its protection fades after just months.

Scientists have found evidence of a drug-resistant form of malaria in Africa.

Still, given the extremely high burden of malaria in Africa — where the majority of the world’s more than 200 million cases a year and 400,000 deaths occur — scientists say the vaccine could still have a major impact.

“This is a huge step forward,” said Julian Rayner, director of the Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, who was not part of the WHO decision. “It’s an imperfect vaccine, but it will still stop hundreds of thousands of children from dying.”

Rayner said the vaccine’s impact on the spread of the mosquito-borne disease was still unclear, but he pointed to the coronavirus vaccines as an encouraging example.

“The last two years have given us a very nuanced understanding of how important vaccines are in saving lives and reducing hospitalizations, even if they don’t directly reduce transmission,” he said.

Dr. Alejandro Cravioto, head of the WHO vaccine group that made the recommendation, said designing a shot against malaria was particularly difficult because it is a parasitic disease spread by mosquitoes.

“We’re confronted with extraordinarily complex organisms,” he said. “We are not yet in reach of a highly efficacious vaccine, but what we have now is a vaccine that can be deployed and that is safe.”

WHO said side effects were rare but sometimes included a fever that could result in temporary convulsions.

Sian Clarke, co-director of the Malaria Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the vaccine would be a useful addition to other tools against the disease that might have exhausted their utility after decades, such as bed nets and insecticides.

Hydroxychloroquine, the drug President Trump hailed as a coronavirus killer, had no beneficial effect for COVID-19 patients in two controlled trials.

“In some countries where it gets really hot, children just sleep outside, so they can’t be protected by a bed net,” Clarke explained. “So obviously if they’ve been vaccinated, they will still be protected.”

In recent years, little significant progress has been made against malaria, Clarke added.

“If we’re going to decrease the disease burden now, we need something else,” she said.

Azra Ghani, chair of infectious diseases at Imperial College London, said she and colleagues estimate that giving the malaria vaccine to children in Africa might result in a 30% reduction overall, with up to 8 million fewer cases and as many as 40,000 fewer deaths per year.

“For people not living in malaria countries, a 30% reduction might not sound like much. But for the people living in those areas, malaria is one of their top concerns,” Ghani said. “A 30% reduction will save a lot of lives and will save mothers [from] bringing in their children to health centers and swamping the health system.”

The WHO guidance would hopefully be a “first step” to making better malaria vaccines, she said. Efforts to produce a second-generation malaria vaccine might be given a boost by the messenger RNA technology used to make two of the most successful COVID-19 vaccines, those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, she added.

“We’ve seen much higher antibody levels from the mRNA vaccines, and they can also be adapted very quickly,” Ghani said, noting that BioNTech recently said it would begin researching a possible malaria shot. “It’s impossible to say how that may affect a malaria vaccine, but we definitely need new options to fight it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.