- Share via

BERLIN — Angela Merkel, that most pragmatic of world leaders, is perhaps the last person one would associate with things mystical.

But the German chancellor, now in the waning days of a titanic 16 years in power, veered away from her trademark empiricism two years ago when she spoke to an American graduating class.

“’In all beginnings dwells a magic force,’” Merkel told a Harvard commencement, quoting the German-Swiss writer Hermann Hesse.

Merkel’s own beginnings were so unassuming that they lend almost fairy-tale overtones to her rise: an obscure scientist who emerged from behind the fallen Berlin Wall to become not just Germany’s first female chancellor, but also one of the world’s most famous women, and Europe’s most powerful leader.

Many now worry what lies ahead without the leader often seen as the glue holding the European Union together. “The European project has always had its fault lines, but they have rarely caused earthquakes,” Ana Palacio, a former foreign minister of Spain, wrote last month on the global affairs website Project Syndicate, musing about potential ruptures within the bloc over defense, economy and foreign policy.

In a post-Merkel era, she wrote, “is the EU in for a tremor — or worse?”

For younger Germans, Merkel has been the only head of government in memory. That simple fact — a confident woman comfortable at the heart of power — will probably prove a lasting legacy.

“My daughters have only known one leader, and it’s been a woman,” said Julius van de Laar, a political consultant in Berlin. “That in itself is substantial.”

Her matter-of-fact mien, unfussy personal style and calmly rational discourse sometimes lent themselves to satire, but Merkel in many ways embodied the self-image Germans aspired to: unadorned, smart, purposeful.

“I’ve got some of the same characteristics as camels have,” she once said, lightly mocking her own somewhat plodding political persona. “I’ve got quite a lot of capacity in my reserve tanks, but there always comes a point when I need to fill them up again.”

Merkel’s landmark tenure saw her hailed for a time as the chief custodian of the liberal Western democratic order — leader of the free world, some went so far as to say — especially after Donald Trump captured the Oval Office. At the head of Europe’s most powerful economy, her leadership was crucial in guiding the continent through the 2008 financial crash and an unprecedented crush of migration in 2015.

But she leaves a distinctly mixed legacy at home, critics say, including a checkered environmental record, an over-reliance on China as a trade partner and a failure to implement badly needed economic and technological reforms.

At 67, Merkel is the first postwar German leader to voluntarily step aside, rather than being voted out of office like her eight male predecessors. But the immense popularity she long enjoyed may not save her center-right party from stinging defeat in Sunday’s election.

Many observers attribute both the successes for which she is lionized, as well as the lapses for which she has been vilified, to a combination of her temperament and a political climate shaped by Germany’s dark 20th century history.

“Germans appreciate her humility and lack of vanity,” said Joern Leonhard, a German author and professor of history at the University of Freiburg. “They like the way she dealt with so many crises over the years, and her incremental way of approaching problems.”

When Merkel became chancellor, sexism was commonplace and constant. In her early days in politics, Merkel was slightingly referred to as “das Madchen”— the girl — or sometimes “Kohl’s girl,” after her then-mentor, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, with whom she eventually broke. The nickname “Mutti” — Mommy — was first bestowed in derision by political rivals, though it was one she later came to tacitly accept, especially when invoked by grateful refugees.

Throughout Merkel’s tenure, imperturbability was a signature trait, and it served her well in face-to-face encounters with self-styled alpha-male leaders such as Russia’s Vladimir Putin and President Trump. An iconic photo of her at a Group of 7 summit in Canada in 2018 captured her leaning forward intently, appearing to admonish a seated, truculent-looking Trump, chin jutting and arms folded across his chest.

Trump’s election victory may have prolonged Merkel’s time in office. Germany has no term limits, and political lore has it that then-President Obama, on a visit to Berlin weeks after the 2016 vote, persuaded a reluctant Merkel to run for one more term.

During Trump’s tumultuous tenure, she “continued to stand up for Western ideals,” said Stefan Kornelius, a biographer of the chancellor and senior editor at the newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung.

“She kept alive the idea that democracies are still alive,” he said.

Raised in East Germany, the Lutheran pastor’s daughter with a doctorate in quantum chemistry entered politics at the relatively advanced age of 35, shortly after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989. Merkel’s scientific training was credited with helping the country navigate a fearsome once-in-a-century public health emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic.

And a moral compass that tilted toward compassion led her to welcome more than a million mainly Syrian refugees in 2015, accompanied by the brisk admonition that “we’ll manage,” though the migrant wave helped galvanize Germany’s far right. She adroitly managed other crises, including the 2010 near-meltdown of the Eurozone economy that threatened the global financial system, though her insistence on severe austerity measures in Greece prompted some to call her coldhearted.

Over the years, her stolid, reassuring qualities proved a balm to a country still haunted by the horrors of the Holocaust, postwar repression in East Germany under communist rule, and reunification more than three decades ago that carried overtones of both liberation and lasting trauma for “Ossies” — East Germans — like her.

Merkel was a master of the German style of “leading from behind” on a continent still wary of strongman-style political figures even more than six decades after the end of World War II. Seen as the quintessential “safe pair of hands,” she often summed up her no-drama political style with a favorite maxim.

“There’s no point banging your head into a wall,” she was fond of saying, “because the wall will always win.”

Never one for public displays of temper, the chancellor in 16 years fired only one of her 55 rotating Cabinet ministers, for insubordination. Longtime Merkel watchers describe a political acumen that helps her instantly read a room and size up an audience.

“Germans don’t like loudmouths; they like those who can lead quietly and from behind,” said Van de Laar. “Merkel has been an incredibly savvy leader in her party who has read shifts in public sentiment exceptionally well.”

Still, critics point to missteps and blind spots: failing to rein in undemocratic practices in EU member states such as Hungary and Poland, progressive rhetoric on climate change that was not always matched by decisive action, an at-times excessively accommodating stance toward China, colored by economic dependence.

Merkel’s tenure overlapped with a disquieting consolidation of far-right forces in German politics, with the hard-line nationalist-populist Alternative for Germany for the first time gaining a foothold in Parliament, in 2017. Questions also persist about Germany’s role in the Western military mission in Afghanistan, whose final unraveling occurred on her watch, and government blunders that exacerbated deadly flooding in the Rhine region in the summer.

And as elsewhere, the pandemic stubbornly refuses to fully recede.

“She mismanaged her exit,” said Leonhard, the history professor. “My judgment is that she’s leaving about four too years late.”

Days before Sunday’s vote, opinion polls indicated Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union, the country’s dominant postwar party, was trailing the center-left Social Democrats and their likely allies, and could end up out of power.

During her four terms, Merkel pushed her party into the political center by ending military conscription, mothballing nuclear power plants, expanding renewable energy, agreeing to shut down coal-burning power plants over the next 15 years, and introducing extensive new government-funded assistance to families.

Those measures, applauded by progressives, siphoned millions of voters away from rival parties on the left. But it also opened space on the far right for the Alternative for Germany, or AfD, which attracted millions of right-wing voters as it morphed into a vociferously anti-immigrant party.

Some political observers describe Merkel as a skilled tactician, but one who has proven less agile in anticipating longer-term policy ramifications.

“She was good at fixing things at critical junctures, but hasn’t developed any strategic vision,” said Leonhard.

He and others said that Merkel leaves office without developing a blueprint for the EU’s future, or for dealings with Russia and China, or for handling the next refugee crisis. She failed to champion much-needed economic reforms, they say, which could eventually dent Germany’s standing as Europe’s financial powerhouse.

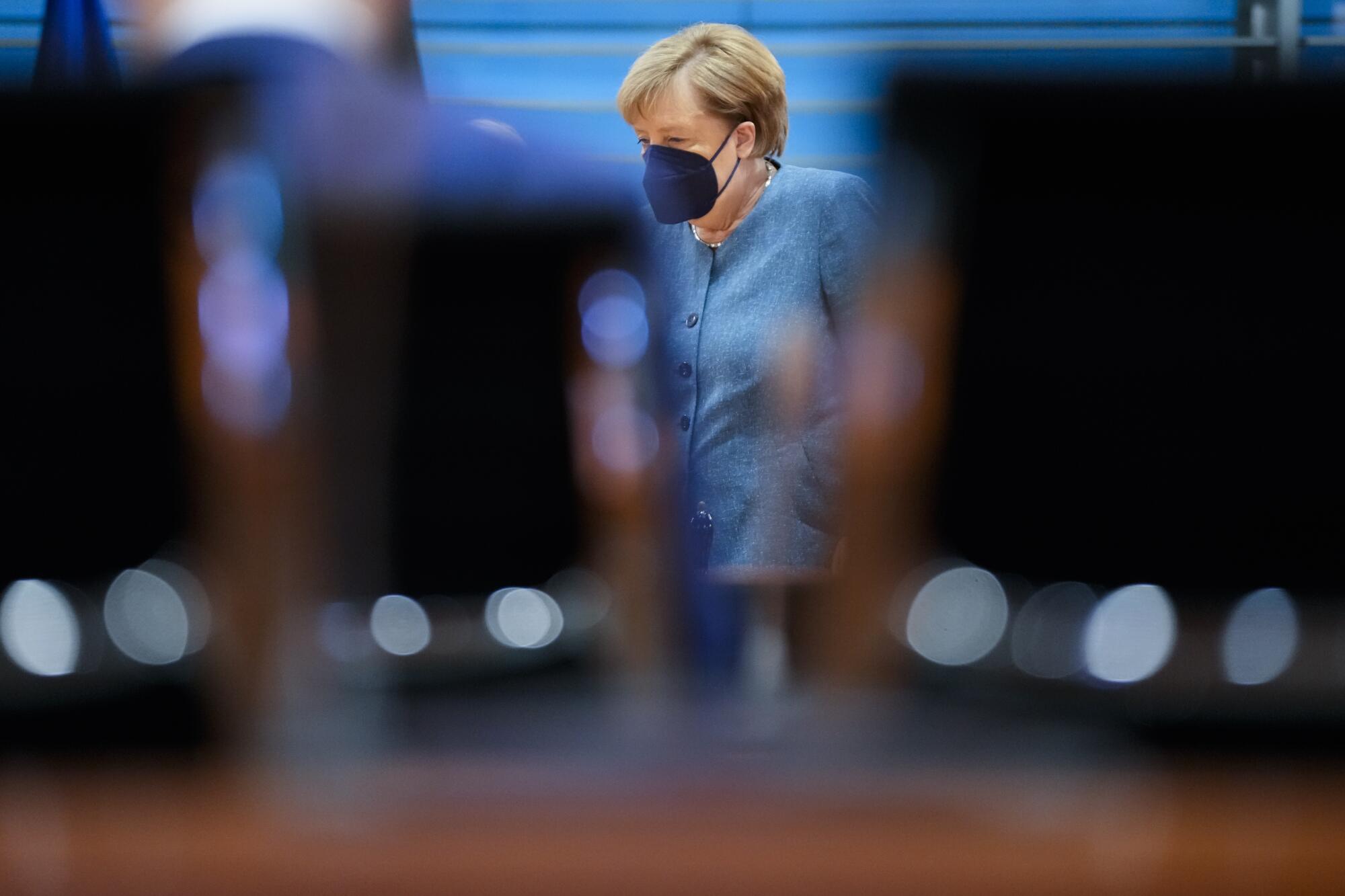

The physical demands of Merkel’s long tenure have been increasingly evident in recent years. She is sometimes visibly fatigued, and in 2019 she suffered public episodes of uncontrolled trembling.

“Merkel has been worn out over the last half-year,” said Kornelius, the biographer and editor. “The pandemic has absorbed any energy she had left, while the floods in July only made things worse.”

Even so, he predicted that history would see the departing chancellor in a favorable light.

“For her legacy, the overall picture should be considered,” said Kornelius. “Germany has gone through some really serious crises, and the overall view is that she has done a good job. She’ll be remembered for 16 years of stability and predictability.”

Special correspondent Kirschbaum reported from Berlin and Times staff writer King from from Washington.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.