Taliban cracks down on protests — and those seeking to leave

- Share via

KABUL, Afghanistan — The Taliban on Wednesday faced the first known street protests against the militant group’s lightning-quick takeover of Afghanistan, and disorder again erupted near Kabul’s international airport, where armed insurgents violently rebuffed Afghans trying to make their way inside to board outgoing flights.

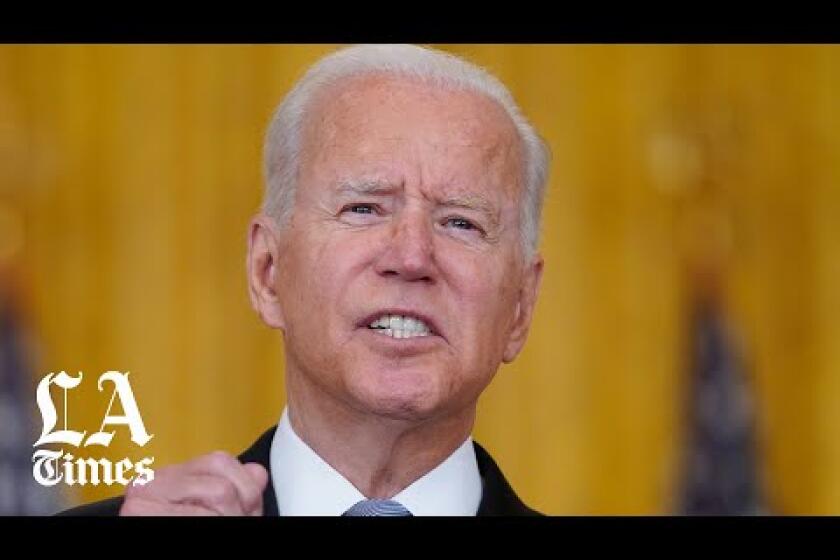

President Biden, in a televised interview, said U.S. troops would stay in Afghanistan beyond their scheduled Aug. 31 departure if necessary to evacuate any Americans wanting to leave.

“If there are American citizens left, we’re going to stay until we get them all out,” Biden said in an interview with ABC News.

But the administration made no such pledge for Afghans desperate to flee because they fear Taliban retribution over their ties to the U.S. military, or others considered vulnerable because of work with Western organizations or advocacy groups.

Three days after having overrun the capital, Kabul, and driven President Ashraf Ghani into exile, the Taliban grappled with elements of basic governance, including a cash-flow crunch in this heavily aid-dependent country.

Ghani, 72, who had dropped out of sight since fleeing Kabul on Sunday, resurfaced in the United Arab Emirates, which announced his presence in a terse communique. The United Arab Emirates is a close American ally.

President Biden hopes to tamp down a political crisis by emphasizing that leaving Afghanistan was the right call, even if the exit is a debacle.

The deposed president, a scholar and technocrat, is now widely reviled in his homeland for having slipped away as the Taliban closed in. He said he left to prevent bloodshed as the group’s fighters seized the country with almost no resistance from the U.S.-trained and equipped military.

Although the Taliban was firmly in charge, with its fighters patrolling the capital in commandeered police and military vehicles, the movement has yet to declare a government.

Taliban representatives in Kabul have been having discussions with figures including former President Hamid Karzai and Abdullah Abdullah, once designated as chief executive in a power-sharing agreement. The talks have brought former foes into close proximity; Karzai and Abdullah met Wednesday with Anas Haqqani, who leads a particularly notorious Taliban splinter group.

The Taliban swept into Kabul and seized power on Sunday after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country.

With so much in flux after the stunning reversals of recent days — the powerful U.S. military to be gone by month’s end, ragtag militia fighters patrolling the streets with automatic weapons slung from their shoulders — thousands of Afghans clung to hopes of making it out of the country.

The U.S.-overseen airlift was picking up pace, military officials said, but the number of those whisked away to safety was dwarfed by the desperate throngs outside the airport, the sole American-controlled enclave in the country. Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said that in the last 24 hours, 18 Air Force C-17 transport planes had carried 2,000 people, including 325 Americans, out of Afghanistan.

With about 4,500 U.S. Marines and soldiers overseeing the effort, the military described operations inside the airport as progressing smoothly, but Kirby batted away questions about the chaos outside the gates, where some Afghans were beaten or rebuffed by young fighters demanding documents as they tried to make their way inside.

Afghan women faced an uncertain future this week as U.S. forces withdrew and the Taliban consolidated control.

A Taliban promise of “safe passage” to the airport for would-be evacuees, touted by the White House, appeared to apply mainly to foreigners, and not even always to them. Kirby, speaking to reporters, summed up the grim dynamic by acknowledging that U.S. forces who once dominated the landscape could do little to help people make their way through the perimeter.

“We’re not outside the airport,” he said. Referring to the Taliban fighters, he said: “And they are.”

Refugee advocacy groups in the United States, meanwhile, prodded the Biden administration to do more to help trapped Afghans in danger from the Taliban because of their past ties to the U.S. military.

The New York-based nonprofit International Refugee Assistance Project filed petitions with the State Department on behalf of about 20,000 Afghan applicants for so-called special immigrant visas, or SIVs. Together with their families, they total about 100,000 people.

The Taliban’s spectacular takeover of Afghanistan has buoyed the spirits of their Islamic brothers-in-arms throughout the world.

“We don’t know that there’s a clear plan at all to evacuate” them, said Becca Heller, the group’s executive director.

Kirby, the Pentagon spokesman, said plans were being made to temporarily house about 22,000 people — SIV recipients and their families — at U.S. military bases. That would accommodate about one-fifth of the estimated number still in Afghanistan.

The Taliban promised to not exact vengeance on people who have opposed the group’s takeover, but some Kabul residents described armed men making unexpected visits to homes and compounds, asking whether anyone there had worked with the U.S. military, the government or with Western organizations.

Many Afghans believe overt resistance to the new rulers would be dangerous or foolhardy, but Wednesday brought a few scattered gestures of defiance, with deadly consequences.

Scores of men reportedly attempted to raise an Afghan national flag in a city square in the eastern city of Jalalabad; the Reuters news agency reported three deaths and about a dozen people injured as Taliban fighters opened fire to disperse them.

A similar small protest was reported in Khost, capital of the eastern province with the same name that borders Pakistan.

For the Taliban leadership, suddenly the stewards of the country’s 38 million people, one immediate worry has already presented itself: cash.

The U.S.-educated head of Afghanistan’s central bank, Ajmal Ahmady, said the country’s supply of hard currency, in the form of U.S. dollars, was “close to zero.” Writing on Twitter, Ahmady explained that most of Afghanistan’s $9 billion in reserves is held outside the country, inaccessible to the new rulers.

That has already led to a plunge in the value of the currency, the afghani, and many people have not been able to access their savings because most banks were not dispensing money.

Analysts said dealing with financial issues may prove much harder for the Taliban than taking over the entire country. Vali Nasr of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies pointed to the heavy dependence on Western funding.

“Those billions went away overnight,” he wrote on Twitter. That, he said, will deeply impact how the Taliban “will or can govern.”

Yam reported from Kabul and King from Washington. Times staff writers Tracy Wilkinson in Washington and Molly Hennessy-Fiske in Houston contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.