Oregon communities struggle to hold off the Bootleg fire, the largest blaze in the U.S.

- Share via

SUMMER LAKE, Ore. — Driving his pickup through smoky, forested roads lining the rim of Summer Lake basin this week, Kevin Leehmann, 40, a longtime rancher and firefighter, was worried.

“This is one road where they’re holding it,” he said of the Bootleg fire, pointing out spot fires as he drove.

He passed California firefighters dousing the spot fires and contractors felling ponderosa pines, beech and quaking aspen to create a fire line. Some of the trees were still charred from past wildfires.

Fire “just chases whatever timber is left,” Leehmann said.

Even rural southern Oregon communities accustomed to massive wildfires in recent years have been alarmed by the size, speed and unpredictability of the long-lasting Bootleg fire, which has grown since July 6 to become the largest in the country.

Fire season started early this year amid a drought across the West, with blazes already burning in California, Idaho, Washington and other parts of Oregon. But the Bootleg fire, named after a local creek, is the largest in the country, a fast-moving, wind-driven conflagration large enough to create its own lightning storms, consuming over 400,000 acres of forest. With more than 2,300 firefighters battling the blaze, it was still only 40% contained by Friday afternoon.

Thursday night the Bootleg fire continued to jump fire lines near Summer Lake, 200 miles southeast of Portland in Oregon’s High Desert.

“We’re focusing on putting out those spot fires, trying to keep the fire from crossing,” said Jason Welsh, a spokesman for the team managing the blaze. “It consumes everything in its path.”

Late Thursday, authorities ordered residents to evacuate from the roughly 70 homes amid the sage, poplars and Russian olive trees that line the shallow, alkali lake. But few did, unwilling to leave livestock, livelihoods and land, especially after having weathered other big fires in recent years — and seeing the fuel they left behind.

Instead of leaving, they monitored smoke atop the lake’s rim. During past fires, once flames reached the rim, winds pushed them down, drawing heat into the basin and making the fires harder to stop. By Thursday, smoke had settled on the rim, thickening into a haze as winds drove the fire toward the scattered houses, pastures, barns, lodge and store at the edge of Summer Lake.

Smoke and heat from the Bootleg Fire in southeastern Oregon are creating so-called ‘fire clouds’ over the blaze.

As Leehmann drove around checking the fire, he dipped into town to talk to the neighbors he was trying to protect. The surrounding county is home to about 7,500, the nearest ambulance a half-hour’s drive away.

A sixth-generation rancher who favors jeans and pearl-snap Wrangler shirts, Leehmann had graduated from Oregon State University and returned to run the Twenty Four Ranch with his wife and two children after his father died in 2010.

The 5,000-acre ranch straddles Highway 31, the town’s main artery, home to the lodge and store. His mother lives up the road, and has been feeding contractors working the fire. His brother, a logger, has been clearing fire lines.

Leehmann works for La Pine Fire District to the north, and three years ago started the local High Desert Rangeland Fire Protection Assn., a 60-person volunteer fire department armed with military surplus firefighting equipment.

Each year since, they’ve faced off against larger wildfires. This week they staged water trucks and fire gear at a grassy field south of town at the foot of the lake’s rim.

On Wednesday, Leehmann stopped at Summer Lake Lodge to talk to owner Gary Brain, also a veteran firefighter, who had technically closed the motel and restaurant due to the Bootleg fire but was still housing firefighters and contractors.

Brain said a rancher he knew had lost 40 head of cattle to the fire. A herd of antelope had been spotted in town, likely pushed down from the hills by the fire, he said. There were mule deer and bighorn sheep in those hills, too — plus bear and cougars.

Leehmann had moved 500 of his cattle from the hills to the basin to avoid the fire. He said his brother had been felling trees to the south when the fire raced in so fast, his crew had to abandon their machines, which burned.

“We have really strange winds,” said Brain, who was wearing a T-shirt from one of the past fires he’d fought. “They’re not predictable. They can blow 20 to 40 mph one way and then turn around and blow the other way off the rim.”

That makes setting backfires to stop blazes like the Bootleg dangerous, the two agreed. Last year, a local sheriff’s deputy threatened to arrest out-of-town fire managers intent on setting a backfire on private land, and they relented.

“We can set a backfire and then have it run over us in 20 to 30 minutes,” Brain said.

Climate change is making the world more prone to floods like those in China and Europe and to heat waves and fires like those in the U.S. and Russia.

Both men were being briefed by the team managing the fire, and knew firefighters were clearing fire lines atop the lake’s rim, along Forest Service Road 2901, which appeared to be their trigger point. If spot fires breached the highway, firefighters planned to set a backfire to stop it.

Both men were worried that the California crews were due to end their two-week deployment this weekend, a time of transition that could allow the fire to grow.

Brain was also nervous about how thick the forest had grown atop the rim, including highly flammable junipers and oily, invasive brush.

“They said you can’t even get a horse through there,” Brain said.

Leehmann nodded.

Later that day, he drove up to check Road 2901, but a Forest Service firefighter from Colorado stopped him, saying crews had the road blocked while they fought spot fires.

Leehmann called a fire manager.

“It’s spotting over the 2901,” he said. “When is the trigger point?”

The manager said he wasn’t going to set a backfire unless firefighters reported significant fire on the other side of the road.

Leehmann thought fire managers were waiting too long to set the backfire on Forest Service land.

“The 2901 was our trigger point,” he said as he drove down the mountain toward town. “After hearing what it’s into and jumped over, I’m a little more nervous. I’d rather they do it here than down there.”

On his way down, Leehmann passed Damon Schulze, who was managing this part of the fire for the state fire marshal’s office. Schulze was headed up the rim, and promised the 200 outside firefighters wouldn’t leave if the fire topped it.

“We’re not going to pull out if there’s any chance of it hitting down below,” he said, which reassured Leehmann, a little.

In town, Leehmann stopped by Summer Lake Store to check in with owner Dale Chiono and split a bottle of red wine. Chiono, a California native and liberal, had moved to the area with his family in 1993 and weathered his share of wildfires. But this year the historic heat wave and massive fires had him thinking about global warming. Leehmann, a Republican, sees the weather patterns as cyclical, but agreed that big fires are here to stay.

“We’re going to have to learn to deal with this,” Chiono said.

A grass fire burning northeast of San Francisco has destroyed or damaged about a dozen homes and prompted evacuations of several streets.

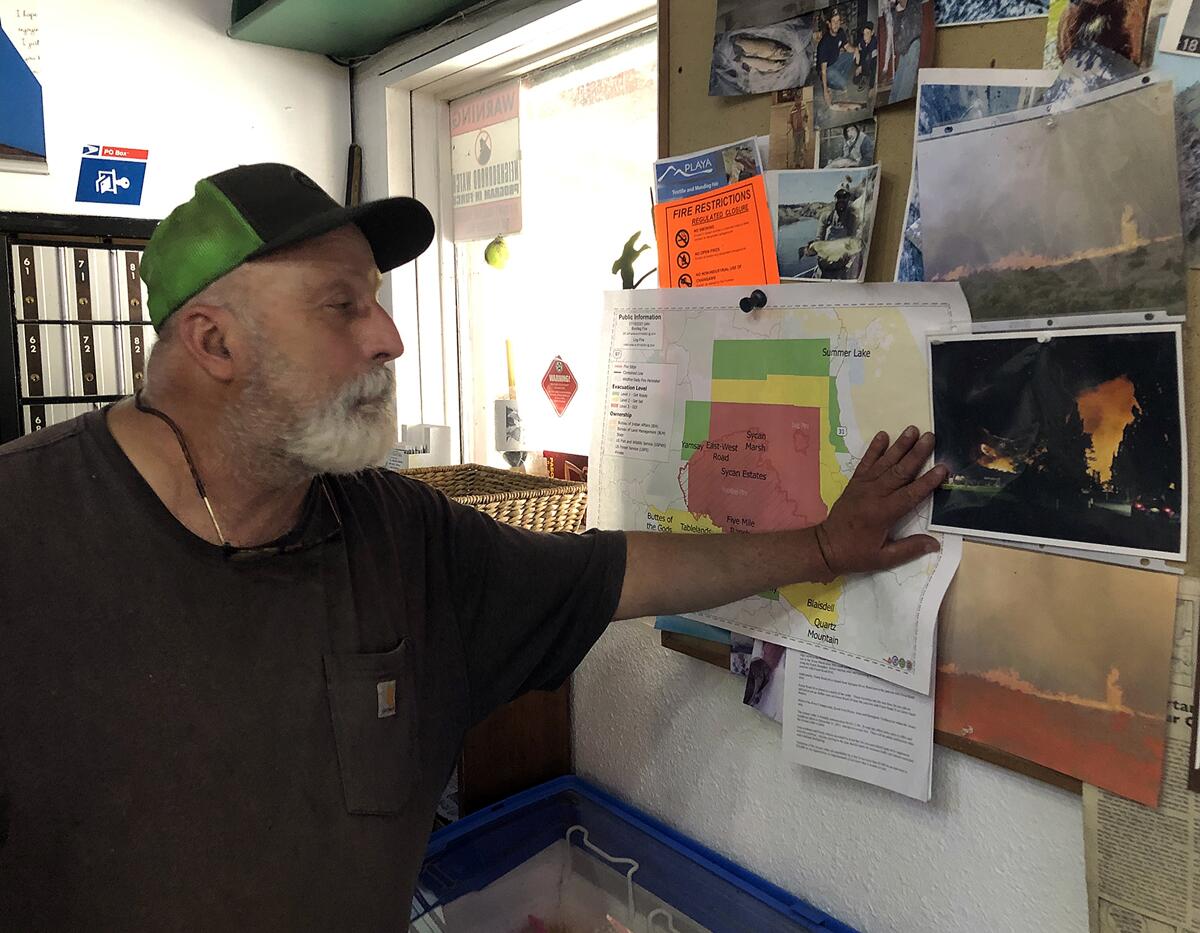

On the wall of the general store, near postal boxes and a mounted antelope head, Chiono had posted his most dramatic fire photos.

“I keep that up there to remind myself to be vigilant,” he said. “You wake up in the morning and you’re hopeful. At night, you see the smoke and the fire engines coming.”

Fire maps were also posted, inside and out.

“The wind rushes downhill around dark. That’s why we get a little jumpy,” Leehmann said. “When fire’s getting pushed that hard, there’s not a lot you can do. If it holds tonight, I’m going to be way more confident.”

That night, the fire lines held. Thursday dawned cool and clear, lifting spirits all over Summer Lake. But by afternoon, smoke had returned to the rim.

Leehmann and his wife drove 2901, past scores of blackened trees, the forest floor a moonscape of ash. He stopped to talk with a contractor he knows who had been cutting fire lines for the last week.

“We’ve lost every line that we’ve put out in front,” Mark Wilcox told Leehmann.

Leehmann’s wife, Erica, considered the thick forest. Like many in town, she and her husband wished the trees had been thinned, or at least salvage-logged, after the last fire.

“When you look at this mess over here, it makes you wonder how they can stop it,” she said.

By the time the Leehmanns drove back to town, deputies were making the rounds, issuing final evacuation orders.

“It passed the trigger point,” a deputy told Chiono and a customer as he handed them an evacuation notice and advised them to leave, saying, “I was here when it came off the rim the last time.”

Chiono said he wasn’t leaving. Neither was his customer. But both left to set up sprinklers and move trailers and other belongings away from the rim. Chiono also checked on some elderly neighbors, who decided to evacuate. Summer Lake Lodge left the lights on for its few remaining guests.

Leehmann activated volunteer firefighters, who assembled at their staging area at dusk. Soon after, a column of dark smoke loomed over the rim, about two miles away. Fire and water trucks sped past on Highway 31, heading up top.

“Hopefully, they catch it,” Leehmann said.

They did. The fire line held. At dawn Friday, it was clear and cool again, but residents knew not to get too hopeful.

“They’re saying a 50% chance it will come over the rim today, tonight,” Leehmann said after a briefing by fire managers Friday morning. “Everybody’s still hanging tight to see what happens.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.