- Share via

FARGO, N.D. — It was an unexpected twist that led the Rev. Yuanlai Zhang — a minister who lived among 13 million others in the hot and humid Chinese city of Shenzhen — to start a new life on the sparse and frigid prairie of North Dakota.

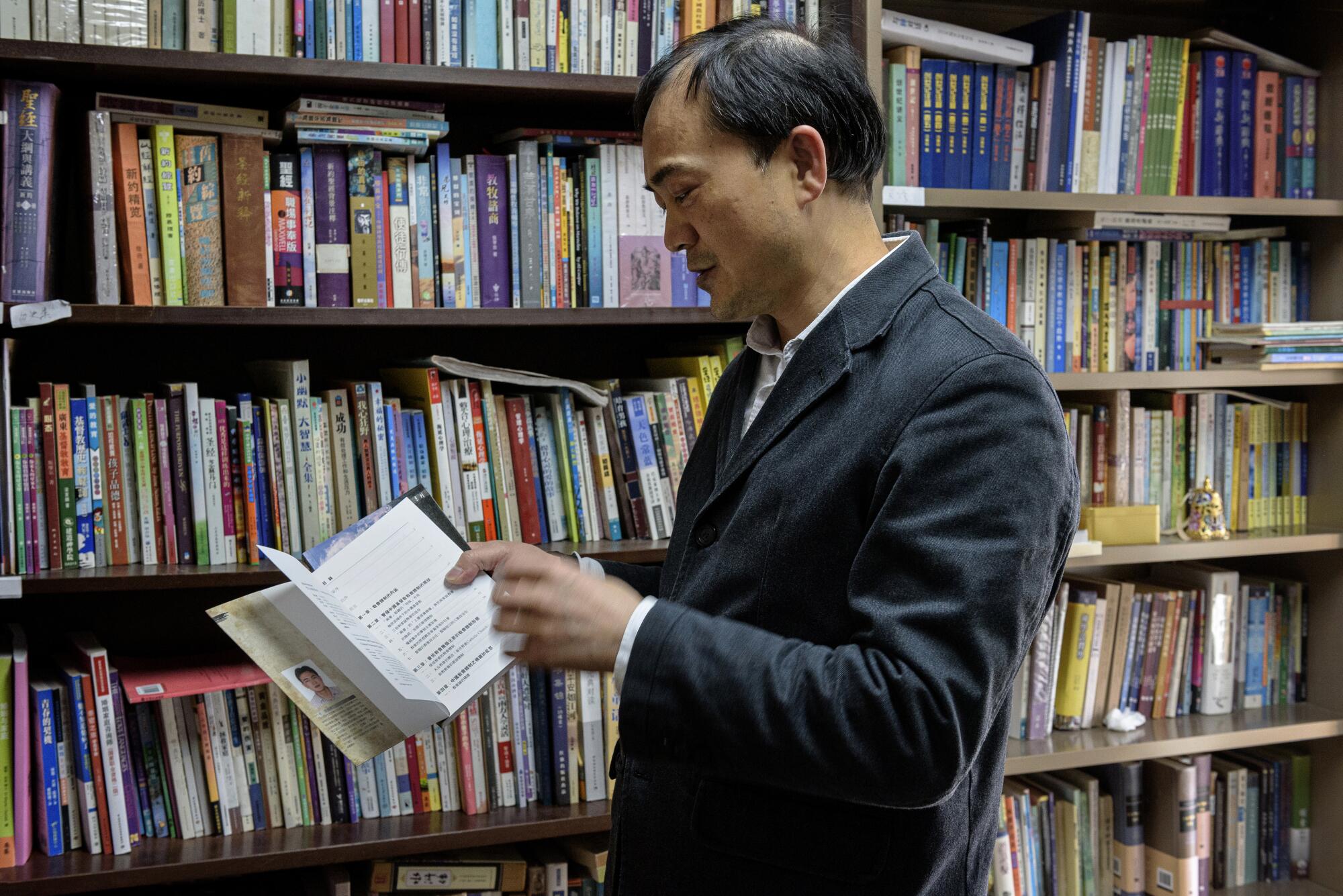

But Zhang has become a man of the plains. A Mandarin-language preacher who travels the state with a Bible and a pressed suit, he lives with his wife and toddler in suburban Fargo. He’s the first full-time pastor at the Red River Valley Chinese Christian Church, which was founded five years ago and whose 50-family congregation is the largest Chinese Christian flock in North Dakota.

“We all knew of New York, Texas and California in China,” said Zhang, 46, who worked for 16 years in his homeland before the burgeoning local Chinese American community recruited him two years ago with a promise that proselytizing — at times a struggle in authoritarian China — would be easier in the United States. “But North Dakota? That was new to us.”

This state is best known for its long white winters, Scandinavian culture and the Oscar-winning film that took its name from Fargo (population 122,000) and gave America a sampling of the unique Upper Midwest accent with its long O’s and its matter-of-fact morality. What doesn’t come to mind is diversity. Yet it’s a place — as Zhang can attest — that has outpaced all others in growing its number of Asian Americans.

A recent report from the Pew Research Center based on U.S. Census Bureau data found that the Asian American population in North Dakota has shot up by 241% since the turn of the century. In second place at 202%: South Dakota. (The bureau, which will release 2020 census reports in pieces over the next several months and has yet to send out the newest data on race, counts Asian Americans separately from Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.)

“The people are nice here. It’s just a little cold,” said Zhang, who has picked up casting for bass on the Sheyenne River and wants to learn how to ice fish for walleye. “It’s nothing like home. But when you are with the Chinese people here, it feels like it.”

California is still the nation’s capital for those whose ancestors hail from countries stretching from Pakistan to the Philippines. The state’s Asian population of 5.9 million grew by more than 2 million since 2000, a rate of 56%. A majority of the nation’s 18.9 million Asian Americans — America’s fastest-growing racial group — live around big cities in California and four other states: New York, Texas, New Jersey and Illinois.

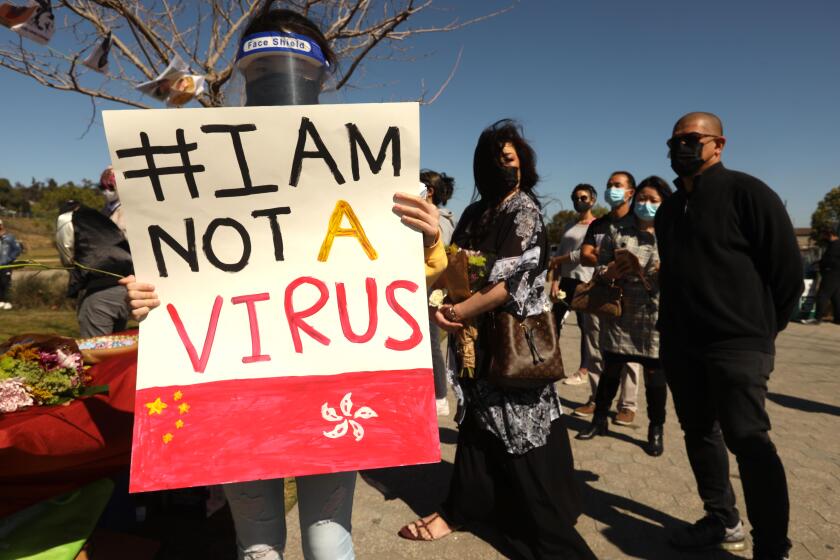

Asian Americans have made headlines in the last year after a historic spike in hate crimes against them. In many cases, perpetrators blamed them for the COVID-19 pandemic, which was first detected in Wuhan, China. The mass shooting at Asian-run spas in the Atlanta area that left dead eight people, including six women of Asian descent, intensified a national discussion over anti-Asian racism and misogyny.

The FBI counted 18 hate crimes against all groups in North Dakota for 2019, the most recent year data are available. Police in Fargo — the largest city with the biggest Asian American population — reported no anti-Asian hate crimes in recent years even as civil rights groups have complained of a climate of harassment. Still, the conversation over anti-Asian racism here is not as charged as in other parts of the nation.

“There are racist people here just like there are everywhere. People might give you looks or are rude or ask where your name is from. But the kind of violence you’re seeing in America, we just don’t have that,” said Yoke-Sim Gunaratne, the executive director of the Cultural Diversity Resources, a nonprofit that offers job training and puts on an annual diversity festival called Pangea. “We’re still mostly white here in this city and state, so maybe we just have a fresher chance to teach people about Asian cultures.”

Last month, a few dozen people gathered at North Dakota State University in Fargo for the first local protest against anti-Asian hatred. It was part of a series of demonstrations that have arisen in this otherwise quiet city since racial justice protests last summer. Vietnamese Americans, Hmong Americans and Chinese Americans joined Black student organizers. Students spoke of the harm from microaggressions and stereotypes. One poster read, “Love us like you love our food.”

Fargo is the heart of a newer, smaller Asia America flourishing in the Upper Midwest and Great Plains. A former railroad village built on Sioux land in the late 19th century along the Red River between North Dakota and Minnesota, its seven-block downtown Broadway strip still highlights its Norwegian immigrant past. Its architecture includes old brick Lutheran churches and family-owned shops housed in two- and four-story buildings dating to the early 1900s, such as one open since 1972 that sells imported Scandinavian chocolates, glassware and blankets.

Wander to the outlying neighborhoods and a more colorful city comes into focus. Between the snowplow lots, agricultural equipment factories, Dollar Trees and Walmarts, Asian American stores and restaurants rise out of tiny strip malls.

A few, like the Asian & American Market, just outside downtown, have been in business for decades, operating as a one-stop shop for Asian, Middle Eastern and African goods. Others, like Gorkha Palace — a Bhutanese, Nepali and Indian cafe near the western edge of this city that’s just over six miles wide — are only just getting ready to open.

The number of Chinese restaurants in Fargo has nearly doubled over the last decade to at least 17. Cultural associations — for Chinese, Bhutanese and Filipino residents — have also begun to spring up.

“When I moved here in the 1980s, you’d have a hard time meeting anybody who was Asian,” Gunaratne said. “People were surprised I spoke fluent English, and we’d have to go to Minneapolis for anything culturally relevant like buying food. Not anymore.”

A Malaysian American who is ethnically Chinese, Gunaratne pointed to a handful of factors that have led to Asian American residents of the state to rise to 13,000 out of a total population of 760,000. It’s a community that puts North Dakota on par with or higher than a fifth of U.S. states in terms of Asian American populations relative to all residents.

Students and professionals come to study and teach at North Dakota State University and stay in Fargo for the cheap housing and plentiful jobs in a state that weathered the 2008 recession and the economic crush of the pandemic better than most. Gunaratne moved here with her late husband, a college professor.

For a little over a decade, Bhutanese refugees fleeing camps in Nepal have been resettled by the thousands in North Dakota, many of them setting up homes in Fargo and petitioning for extended families to join. So too have Congolese, Sudanese, Somali and Iraqi newcomers. Tech, medical and manufacturing companies like Microsoft, Sanford and John Deere have grown over the years, taking in low- and high-skilled workers. Many Asian Americans have started their own businesses — often in food.

“I don’t think most people in America know that Asians exist in places like this,” said Shankar Subba, 34, who was one of the first Bhutanese in town when he moved from a refugee camp in Nepal a dozen years ago.

At his South Asian spices store, Himalayan Grocery, crates brim with red chilis for making ema datshi, a spicy Bhutanese dish of chili and yak cheese served with rice. His freezer stores pre-rolled momos, dumplings stuffed with chicken or beef. His father, mother and four brothers — the wider family immigrated to Fargo a few years afterward — all work at the store, which sits across from a Hobby Lobby and a Denny’s.

Subba is recruiting a chef to open Ghorka Palace, a restaurant that will be attached to the shop. A former factory worker, he’s married to another Bhutanese refugee who left Arizona for Fargo. Recent reports of hate crimes elsewhere have caused Subba little concern. The one time he felt slighted, he said, was before he became a business owner and was passed over for a promotion a few years ago at a factory while a less experienced white man got the job.

His 29-year-old brother, Ajit Subba, the only child who lives with their parents, feels differently.

A business administration student, he was until recently looking to leave for somewhere warmer and more diverse. Texas, Florida and California were among the possibilities.

“Since I’ve read all these reports of racism around the country, I feel like I cannot move,” Ajit Subba said. “If I move, my parents have to come with me too. They don’t speak English. What if somebody tries to hurt them? I don’t let them walk alone and I tell them to use their phone to record anybody who tries anything with them. They say nothing will happen to them if they mind their business. I tell them it doesn’t work that way.”

Five years ago, local Chinese American professionals launched United Chinese Americans Fargo-Moorhead for their growing community. The association began by organizing cultural events, such as the annual Chinese New Year festival, volunteering at the city’s popular summer air show and connecting American-born kids to Mandarin classes.

The group often meets at Super Buffet, one of the city’s older Chinese restaurants that was founded by a family that moved from Ohio and Minnesota in search of a place with less business competition. It’s next door to the Subba family shop. On a recent day, members swapped stories over fried rice, fresh spring rolls and roasted duck.

“Recently when I was working outside of Fargo, I was called ‘ching ching,’” said Wei Lin, an engineering professor and elder of the community who moved in 1997 from Buffalo, N.Y. The name-calling happened as he helped rural towns do sewage analysis to detect community spread of COVID-19. “I just sort of let it go and kept on speaking, as I think the man was just trying to be a little too friendly instead of mean and I didn’t want to make it into an argument.”

Jun Yang, a 37-year-old water resource engineer who emigrated 11 years ago from Lanzhou, China, for a PhD program at North Dakota State University, said he had heard bad stories yet only experienced good ones himself.

“One Chinese man told me he was at the gas station and told to ‘go back to your country.’ He moved to Texas — for a new job, I think, not because of racism,” Yang said. “But the other day, a white man came up to me on the street in my neighborhood and decided to apologize to me for what’s happening to Asians in the country. That was a little unusual.”

Zhang, the pastor, was also at the dinner. He had also heard of racist run-ins but said they were rare. He recalled the beginning of the pandemic when the church gave away thousands of face masks to people in Fargo, an act that was in part an effort to combat the anti-Chinese views growing across the nation.

An author of more than 10 books in his native tongue, he was studying to improve his English and had become accustomed to odd looks he sometimes drew. He decided it was probably his thick accent, not racism, that brought the attention. It’s been hard to adjust to this new land. He was thankful, though. He never planned on it, but his faith and an adventurous spirit delivered him to the cold plains and small city his family now calls home.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.