Capitol Police were warned of violence before riot, says acting Chief Yogananda Pittman

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Capitol Police knew armed extremists were primed for violence at the iconic building on Jan. 6 and even provided officers with assault rifles to protect lawmakers, the acting chief acknowledged Wednesday. But the wild invasion of the Capitol was far worse than police expected, leaving them unprepared to fight it off.

A day earlier, her predecessor as chief testified that police expected an enraged but more typical protest crowd of Donald Trump supporters. But Acting Chief Yogananda Pittman said intelligence collected ahead of the riot prompted the agency to take extraordinary measures, including the special arming of officers, intercepting radio frequencies used by the invaders and deploying spies at the Ellipse rally where President Trump was sending his supporters marching to the Capitol to “fight like hell.”

Pittman’s testimony, submitted ahead of a House hearing on Thursday, provides the most detailed account yet of the intelligence and preparations by U.S. Capitol Police ahead of the insurrection when thousands of pro-Trump rioters invaded the Capitol aiming to stop Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s election victory over Trump.

Three days earlier, Capitol Police distributed an internal intelligence assessment warning that militia members, white supremacists and other extremist groups were likely to participate, that demonstrators would be armed and that it was possible they would come to the Capitol to try to disrupt the vote, Pittman says.

“Based on the assessment, the Department understood that this demonstration would be unlike the previous demonstrations held by protesters with similar ideologies in November and December 2020,” Pittman says in her prepared remarks.

Former security officials testified before Congress on Tuesday, saying they didn’t know extremists planned to storm the Capitol building on Jan. 6.

At the same time, she argues police didn’t have enough intelligence to predict the violent insurrection that resulted in five deaths, including that of a Capitol Police officer. They prepared for trouble but not an invasion.

“Although the Department’s January 3rd Special Assessment foretold of a significant likelihood for violence on Capitol grounds by extremists groups, it did not identify a specific credible threat indicating that thousands of American citizens would descend upon the U.S. Capitol attacking police officers with the goal of breaking into the U.S. Capitol Building to harm Members and prevent the certification of Electoral College votes,” Pittman says in her testimony.

Steven Sund, the police force’s former chief who resigned after the riot, testified Tuesday that the intelligence assessment warned white supremacists, members of the far-right Proud Boys and leftist antifa were expected to be in the crowd and might become violent.

“We had planned for the possibility of violence, the possibility of some people being armed, not the possibility of a coordinated military style attack involving thousands against the Capitol,” Sund said.

The FBI also forwarded a warning to local law enforcement officials about online postings that a “war” was coming. But Pittman said it still wasn’t enough to prepare for the mob that attacked the Capitol.

Officers were vastly outnumbered as thousands of rioters descended on the building, some of them wielding planks of wood, stun guns, bear spray and metal pipes as they broke through windows and doors and stormed through the Capitol. Officers were hit with barricades, shoved to the ground, trapped between doors, beaten and bloodied as members of Congress were evacuated and congressional staffers cowered in offices.

Christian Secor, who was charged with federal crimes for his alleged role in the Capitol riot, had stirred up tensions over free speech.

Should police have been better prepared?

With the amount of information available to the Capitol Police, it’s surprising that they didn’t take additional steps to reinforce security and protect their officers, said Tom Warrick, a former counter-terrorism official who served in the Obama administration.

“On Jan. 6, the one strategic location in the entire U.S. national capital region that had to be defended was the U.S. Capitol,” said Warrick, now with the Atlantic Council. “So it was really disappointing you have people testifying that ‘we didn’t know there would be violence.’ When you are the target, you assume that things like that can happen even if you don’t have the intel.”

Even without access to secure intelligence, there were months of warning signs in public view that rioters would try to do what they did, said Bruce Hoffman, a former commissioner on the 9/11 Review Commission and a senior fellow for counter-terrorism and homeland security for the Council on Foreign Relations.

A plot uncovered by federal law enforcement to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer was a major red flag, and many of the rioters went on social media to echo Trump’s calls to “stop the steal” and speculate about violence.

“Historically, the default is always to blame it on an intelligence failure when often there may well be other reasons,” Hoffman said. “I think it was very obvious to anyone ... that a confrontation was going to occur.”

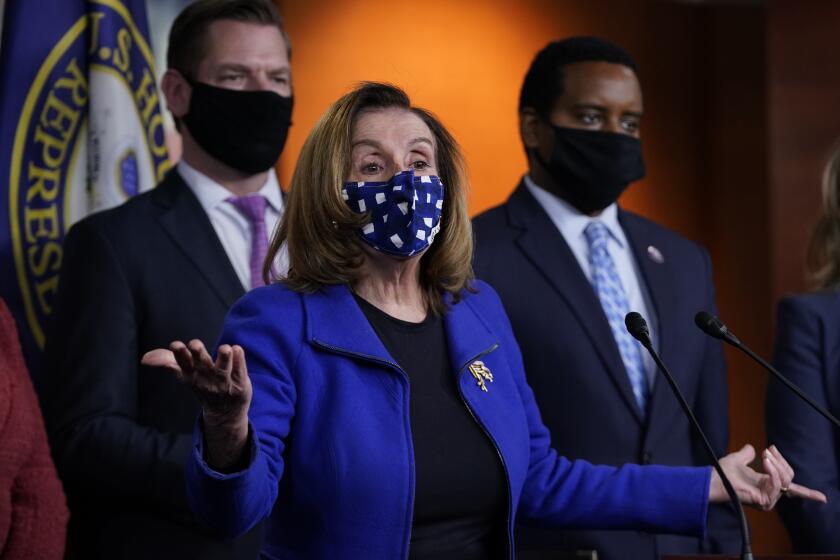

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi says Congress will establish an independent, Sept. 11-style commission to look into the deadly insurrection at U.S. Capitol.

Pittman also says the department faced “internal challenges” as it responded to the riot. Officers didn’t properly lock down the Capitol complex, even after an order had been given over the radio to do so. She also says that officers didn’t understand when they were allowed to use deadly force, and that less-than-lethal weapons that officers had were not as successful as they expected.

While Pittman says in her testimony that that sergeants and lieutenants were supposed to pass on intelligence to the department’s rank and file, many officers have said they were given little or no information or training for what they would face. Four officers said shortly after the riot that they heard nothing from Sund, Pittman, or other top commanders as the building was breached. Officers were left in many cases to improvise or try to save colleagues facing peril.

Pittman also faces internal pressure from her rank and file, particularly after the Capitol Police union issued a vote of no confidence against her last week. She must also lead the department through the start of several investigations into how law enforcement failed to protect the building.

Capitol Police are investigating the actions of 35 police officers on the day of the riot; six of those officers have been suspended with pay, a police spokesman said.

Merchant reported from Houston. Associated Press writers Ben Fox and Eric Tucker contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.