The first COVID-19 vaccines won’t end the U.S. crisis right away

- Share via

Don’t even think of putting your mask away anytime soon.

Despite the expected arrival of the first COVID-19 vaccines in just a few weeks, it could take several months — probably well into 2021 — before things get back to something close to normal in the U.S. and Americans can once again go to the movies, cheer at an NBA game or give Grandma a hug.

The first, limited shipments of the vaccine would mark just the beginning of what could be a long and messy road toward the end of the pandemic that has upended life and killed more than a quarter-million people in the U.S. In the meantime, Americans are being warned not to let their guard down.

“If you’re fighting a battle and the cavalry is on the way, you don’t stop shooting; you keep going until the cavalry gets here, and then you might even want to continue fighting,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, said last week.

There are still many unknowns when it comes to the pandemic, but the early signs of success for two experimental COVID-19 vaccines make a few things clear.

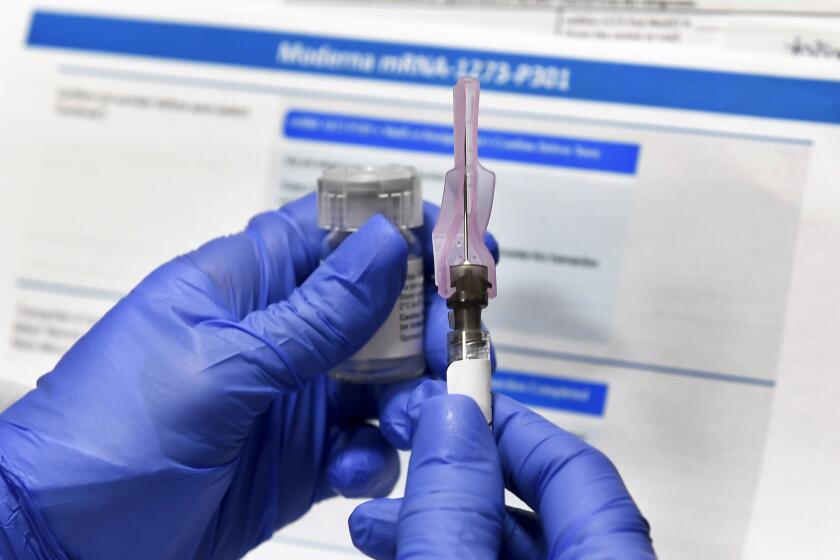

This week, AstraZeneca became the third vaccine maker to say early data indicates its shots are highly effective. Pfizer last week asked the Food and Drug Administration for emergency authorization to begin distributing its vaccine, and Moderna is expected to do the same any day. Federal officials say the first doses will ship within a day of authorization.

But most people will probably have to wait months for shots to become widely available. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines also both require two doses, meaning people will have to go back for a second shot after three and four weeks, respectively, to get the full protection.

Moncef Slaoui, head of the U.S. vaccine development effort, said on CNN on Sunday that early data on the Pfizer and Moderna shots suggest about 70% of the population would need to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity — a milestone he said is likely to be reached in May.

But along the way, experts say the logistical challenges of the biggest vaccination campaign in U.S. history and public fear and misinformation could hinder the effort and kick the end of the pandemic further down the road.

“It’s going to be a slow process and it’s going to be a process with ups and downs, like we’ve seen already,” said Dr. Bill Moss, an infectious disease expert at Johns Hopkins University.

California and other states are racing to finalize plans for who will get the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines and how they will be delivered.

Once federal officials give a vaccine the go-ahead, doses that are already being stockpiled will be deployed with the goal of “putting needles in people’s arms” within 24 to 48 hours, said Paul Mango, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services official involved in the Operation Warp Speed effort to develop COVID-19 vaccines.

Those first shipments are expected to be limited and will be directed to high-risk groups at designated locations, such as frontline healthcare workers at hospitals.

Federal and state officials are still figuring out exactly how to prioritize those most at risk, including the elderly, prison inmates and homeless people. By the end of January, HHS officials say, all senior citizens should be able to get shots, assuming a vaccine becomes available by the end of 2020.

For everyone else, they expect widespread availability of vaccines would start a couple of months later.

To make shots easily accessible, state and federal officials are enlisting a vast network of providers, such as pharmacies and doctor’s offices.

But some worry long lines won’t be the problem.

“One of the things that may be a factor that hasn’t been discussed that much is: How many will be willing to be vaccinated?” said Christine Finley, director of Vermont’s immunization program. She noted that the accelerated development of the vaccine and the politics around it have fueled worries about safety.

Top executives of nine drugmakers likely to produce the first coronavirus vaccines signed a pledge to boost public confidence in approved vaccines.

Even if the first vaccines prove as effective as suggested by early data, they won’t have much impact if enough people don’t get them.

Vaccines aren’t always effective in everyone: Over the past decade, for example, seasonal flu vaccines have been effective in from 20% to 60% of people who get them.

AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Moderna say early trial data suggests their vaccine candidates are about 90% or more effective. But those rates could change by the time the studies end.

Also, the definition of “effective” can vary.

Rather than prevent infection entirely, the first COVID-19 vaccines might only prevent illness. Vaccinated people might still be able to contract and transmit the virus, another reason experts say masks will remain crucial for some time.

Another important aspect of vaccines: They can take awhile to work.

The first shot of a COVID-19 vaccine might bring about a degree of protection within a couple of weeks, meaning people who get infected might not get as sick as they otherwise would. But full protection could take up to two weeks after the second shot — or about six weeks after the first shot, said Deborah Fuller, a vaccine expert at the University of Washington.

People who don’t understand that lag could mistakenly think the vaccine made them sick if they happen to come down with COVID-19 soon after a shot. People might also blame the vaccine for unrelated health problems and amplify those fears online.

“All you need is a few people getting on social media,” Moss said.

Distributing COVID-19 vaccine will be biggest health operation in L.A. history. Can the bureaucracy pull it off?

There’s also the possibility of real side effects. COVID-19 vaccine trials have to include at least 30,000 people, but the chances of a rare side effect turning up are more likely as growing numbers of people are vaccinated.

Even if a link between the vaccine and a possible side effect seems likely, distribution of the shots might not be halted if the risk is deemed small and is outweighed by the benefits, said Dr. Wilbur Chen, a vaccine expert at the University of Maryland.

But Chen said public health officials will need to clearly explain the relative risks to avoid public panic.

Depending on whether the virus mutates in coming years and how long the vaccine’s protection lasts, booster shots later on may also be necessary, said Dr. Edward Belongia, a vaccine researcher with the Marshfield Clinic Research Institute in Wisconsin.

Belongia and many others say the coronavirus won’t ever be stamped out and will become one of the many seasonal viruses that sicken people. How quickly will vaccines help reduce the threat of the virus to that level?

“At this point, we just need to wait and see,” Belongia said.