- Share via

RAWALPINDI, Pakistan — Sakandar Hayat wanted it to be a special Ramadan. He and his son Arafat left northwestern China and crossed the border into Hayat’s native Pakistan. It was a journey to bring father and son closer together. But it would end up tearing their family apart.

The two had been in Pakistan for three weeks when they received a phone call from back home in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. Hayat’s wife, an ethnic Uighur, had been detained. He and Arafat raced to the border, where Chinese police were waiting. They arrested Arafat, a Uighur like his mother, saying he would be questioned on what he had done in Pakistan.

“Don’t separate us,” Hayat begged the police. “Question him in front of me. I’ll be silent and he will speak truth.”

“You’ll have your son back in a week,” the police told him that day in 2017.

Arafat would be lost to him for two years.

Hayat is one of hundreds of Pakistanis who have suffered from China’s suppression of Muslims in the Xinjiang territory, which is home to about 10 million ethnic Uighurs. Rich in minerals, gas and oil, the vast region is dotted with concentration camps where Chinese authorities have locked up more than a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities, according to human rights groups, survivors, victims’ families and United Nations experts.

But increasingly, China’s campaign against Uighurs has spilled across its borders, entangling men such as Hayat, a Pakistani garment trader who, with his wife, raised three children while trapped between the politics and ambitions of two countries.

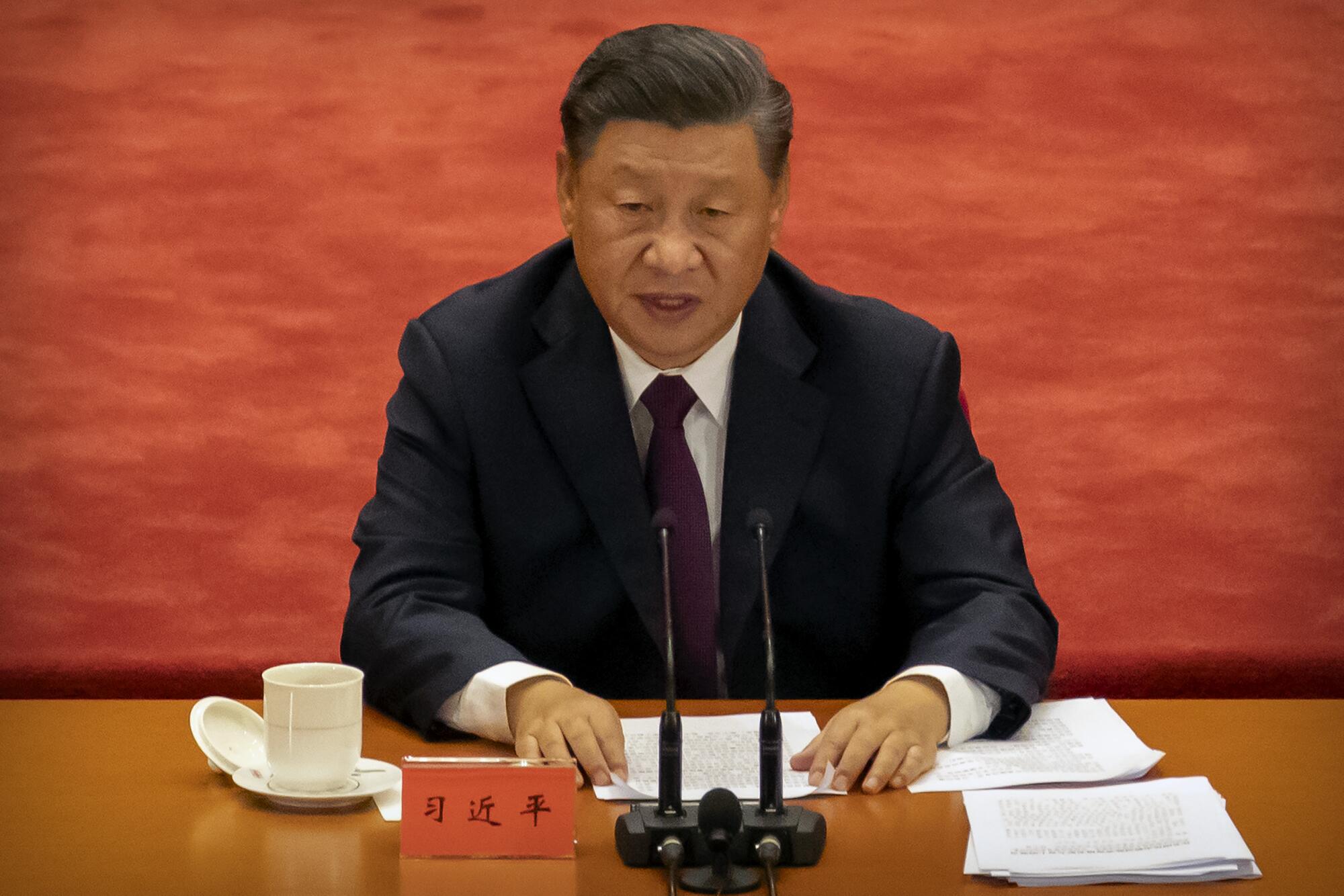

Hayat’s saga reflects how Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s hard-line vision of crushing dissent extends beyond consolidation of power at home to blocking criticism from foreign governments, even when their own citizens are mistreated. The silence of Pakistan, which has been outspoken on oppression of Muslims across the world but has refrained from criticizing China — a major economic benefactor and potential provider of COVID-19 vaccines — reflects how many nations are wary of jeopardizing their ties to Beijing.

The Times interviewed four Pakistanis married to Uighurs who have been separated from their families, two Pakistani Uighurs who have been threatened by Pakistani security forces, and one Chinese Uighur who fled abroad via Pakistan after being detained in a camp. Fearing retaliation from authorities in both countries, several of them asked not to be named, although The Times reviewed their marriage and identification documents.

“It is very hard to leave your heart, your children, to live in a place worse than a prison,” Hayat said. After his wife and Arafat, who was then 19, were detained, Hayat was denied a visa to China for two years. The couple’s two daughters, who were 7 and 12 at the time, were sent to an orphanage in Kashgar without his consent.

He pleaded with Chinese and Pakistani officials for information on his family with no response until 2019, when Chinese officials said his son was receiving “education,” a euphemism for the camps where Beijing says minorities are receiving “vocational training” to combat “extremism, separatism and terrorism.”

Those who have been inside the camps tell a different story. Mohammed, a Uighur from southern Xinjiang who had been doing business between China and Pakistan since the early 2000s, told The Times that he had been detained for seven months. He was arrested when he crossed the border in June 2018, he said, then held in a camp with his hands chained together in a room of 35 people.

Every morning, they woke up at 4 for lectures about the Chinese Communist Party’s care for Uighurs, he said.

“The party is feeding you,” he remembered being told. “Uighurs are nothing without this party. If there was no Communist Party, Uighurs would have died of hunger.”

He and others were then forced to sing songs praising the party and Xi. After that they did morning exercise, running in circles as the sun rose. They were fed hot water and a piece of bread, and led to five hours of Chinese-language lessons. No one was allowed to speak Uighur, Mohammed said.

Once every month or so, the camp guards would make detainees watch as they burned prayer mats, beads and religious books that they’d confiscated from Uighur homes.

“You people are not Turks. Uighurs are Chinese. You are one of us, Chinese,” they would tell the detainees.

China is a dungeon, our homes are torture cells, and death or execution is waiting for me and my family there.

— Mohammed, a Uighur from southern Xinjiang

He said camp guards beat him with electric batons, questioned why he went to Pakistan and accused him of working for the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, an anti-China militant group that has sent fighters to Syria. They asked if he prayed, and when he said “no,” they beat him and said, “Are you not a Muslim?”

“If you talk slowly they will beat you. If you become loud they will beat you more. I asked them: ‘How should I talk? How should I answer? Don’t beat me. I will answer everything clearly,’” Mohammed said. But the beatings persisted.

Mohammed was finally released on condition that he bring his wife and children in Pakistan back to Xinjiang and act as an informer for Chinese authorities. His other family members in Xinjiang would be collateral.

“But I will not go back to China,” he told The Times in an interview in Rawalpindi. Scars from the chains, beatings and electric shocks still marked his wrists, arms, back and feet. “China is a dungeon, our homes are torture cells, and death or execution is waiting for me and my family there.”

A few days later, he left Pakistan as well. The Times was not able to confirm what happened to the family members he left behind.

Although Pakistan is one of many Muslim nations that has refused to criticize China’s oppression of Uighurs, “it’s also probably the country with the least room for maneuver,” said Andrew Small, a senior transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

China provides Pakistan with tens of billions of dollars in loans and expanding military cooperation. Pakistan buys nearly 40% of China’s arms exports. It is also the flagship site for Xi’s Belt and Road global infrastructure initiative, which includes a 2,000-mile “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor” of roads and railways from Kashgar to the Arabian Sea.

Given this relationship, Pakistan has always felt “obliged to be accommodating” with Chinese requests, “even when it wasn’t entirely comfortable,” Small said.

Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper recently published a column about how Chinese pressures to quiet criticism of investment projects or the Uighur plight were strengthening authoritarianism in the Muslim nation. Censorship in Pakistan was “already in overdrive” before Chinese influence, the column noted: “But free speech opponents will be grateful for a patron that shares their disdain for dissent.”

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has repeatedly denied knowledge of China’s actions in Xinjiang. He told the Financial Times, Al Jazeera and the Turkish news channel TRT World in interviews last year that he “doesn’t know much” about the Uighurs.

“I will say one thing about China,” he told Al Jazeera. “For Pakistan, China has been the best friend.”

Pakistan also joined 36 other countries including Russia, Saudi Arabia and Syria in signing a letter to the United Nations last year defending China’s “education and training centers” and praising China’s “remarkable achievements in the field of human rights.”

China’s grip on Xinjiang, which is more than triple the size of California, wasn’t always so brutal, said Bacha, a 63-year-old Pakistani trader from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. He had lived in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital, since 1988 and married a Uighur there in 2001.

Security measures had escalated dramatically in 2009, after riots in Urumqi left nearly 200 people dead. Ethnic tensions rose as the Communist Party encouraged Han Chinese people and companies to move to Xinjiang. Many Uighurs viewed them as opportunists who took the best jobs and exploited Xinjiang’s resources at the expense of locals.

The Chinese government tried to quell unrest through assimilation and force, banning religious dress, promoting patriotic education and blanketing the land with checkpoints, police and security cameras.

But ethnic violence escalated alongside state violence: Uighur attacks on civilians and police erupted in 2012, 2013, and 2014, including an attempted plane hijacking, knife assaults, bombings, and a car crash into a crowd in Tiananmen Square.

In 2016, a party hard-liner named Chen Quanguo, known for cracking down on Tibet, came to Xinjiang. Chen engineered a mass surveillance and detention campaign, implemented through a mandatory state app that collected data from Uighur phones and determined who to put in camps by algorithm.

Detainees were chosen for reasons as innocuous as growing beards, using WhatsApp, or communicating with family members abroad, according to reporting by Human Rights Watch and Chinese government documents leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Han cadres were also sent into Uighur homes, often moving in with Uighur women and children while their men were detained, to drill them in “loving the Party,” rejecting religion and becoming more “Chinese.”

“You are being watched and instructed what to do,” Bacha said. “Fear looms over your head. Fear travels in the air.”

In 2016, Bacha’s in-laws fled to Turkey with two of his children. Chinese police then detained his wife and three other children, ages 3, 4, and 5.

After petitioning the Pakistani Foreign Ministry and Chinese authorities, he was told recently that he could get Pakistani passports to bring his children out — but not his wife. She has been sentenced to 6 ½ years in prison. Authorities have not explained why.

Members of the Pakistani Uighur community, comprising families who left Xinjiang and became Pakistani citizens in the late 1940s, spoke of similar intimidation inside the Muslim nation.

One Pakistani Uighur shop owner in Rawalpindi told The Times that he had been detained for two weeks by plainclothes Pakistani security officers in late 2018. He said he was taken from his home in a black hood, chained in a dark room and questioned if he had connections with the East Turkestan Islamic Movement.

“The interrogators told me, ‘Don’t raise a voice against China here, even in personal gatherings,’” said the shop owner, 53, who believes his uncle in Yarkand, in Xinjiang, is also in a camp. Fearful of endangering his relatives in Xinjiang further, he has not contacted them for three years.

Another Pakistani Uighur, Muhammed Umer Khan, has faced pressure from Pakistani authorities for trying to promote Uighur language and culture. Khan, whose parents migrated to Pakistan from Kashgar in 1967 to escape oppression by the Chinese Communist Party, founded the Umer Uyghur Trust in 2008 and opened a small school near his home in Rawalpindi in 2010.

But Pakistani authorities soon visited Khan, ordering him to close the school because it was “damaging China-Pakistan relations.” When he refused, he said, plainclothes government agents destroyed the school, smashing computers and confiscating study materials.

Khan tried to reopen the school in 2015, but it was forcibly closed again within one month. In 2011, he and his brother were temporarily banned from leaving Pakistan. In 2017, he was detained by Pakistani officers for nine days.

Since early 2019, an organization funded by the Chinese Embassy called the “Ex-Chinese Assn.,” which runs Mandarin schools for Uighurs in Pakistan, has also begun asking Pakistani Uighur families to register the names and addresses of their family members in China.

Pakistani Uighurs were told that the Ex-Chinese Assn. wanted their relatives’ information to ensure their children were eligible for the schools. But Khan worried the information would be used for surveillance — or to arrange the extradition of Pakistani Uighurs to China.

“I am afraid,” said Khan, 47. “Even though we are living in a free Muslim country, China holds so much suppression over the Uighur community here. So then what are they doing with Uighur people living in China?”

Azeem Khan, the general secretary of the Ex-Chinese Assn., did not respond to requests for comment.

Members of the Pakistani-Uighur community say some Uighur families of Pakistanis were released from camps late last year, in part because of pressure from international media and diplomats. The Chinese government also claimed in December 2019 that “students” in the camps had “graduated.”

But release doesn’t mean freedom. Many move straight from camps to prison or factory labor and are still unable to leave Xinjiang. When a resurgence of the coronavirus hit the region this summer, much of the province was put under an extremely strict lockdown, with residents confined to their homes and forced by local authorities to drink traditional Chinese medicine.

In 2019, a Times reporter asked Zhao Lijian, then deputy chief of mission at the Chinese Embassy in Islamabad, for comment on the Pakistan-Xinjiang cases.

“We have been helping these Pakistani husbands in all possible ways,” he said in a phone call. “The Chinese Embassy is providing assistance to the families.”

Then he sent separate WhatsApp messages to the reporter, who is Pakistani, asking to not publish The Times story.

“There are negative stories against China in Western countries. They are mostly propaganda against China.… They have an agenda to oppose China,” wrote Zhao, who is now a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry. “Pls restrain yourself from doing this in Pakistan.”

Authorities in Xinjiang declined to comment. The Chinese Foreign Ministry said in response to further inquiry from The Times in August that “forces with ulterior motive have been nonstop instigating, hyping, creating rumors, and slandering” its policies in Xinjiang, but that “China lauds Pakistan for always firmly supporting the Chinese stance on the Xinjiang question. The two sides have used friendly negotiation on the basis of mutual respect to address related affairs.”

Hayat, the man who lost his son at the border, is still fighting to reunite with his family. In July 2019, Hayat finally received a visa and went to Kashgar, where he stayed in a hotel because authorities would not allow him to stay at home. His wife, who had been transferred from a camp to a prison, was released that September. She suffered liver and heart problems after detention, but wouldn’t talk about what happened inside.

Hayat’s son, Arafat, was also released on condition that he sign a two-year labor contract with a Chinese telecommunications company. He was promised a salary of $250 a month — but some months he received less than $200, and others he wasn’t paid at all, Hayat said — and can only leave two days a week.

Hayat said he had visited government officials in Kashgar and asked for his son’s release from the work program, but no one responded. He returned to Pakistan in December when his visa expired and is trying to get Pakistani passports for his children so they can leave.

There were rumors in the community that other Pakistani spouses had agreed to deals with Pakistani and Chinese intelligence services, in which they promised to not speak about what happened if they could get their families back.

They became like Hayat’s wife after her release, he said: alive, but silent.

This is the second in a series of occasional articles about the effect China’s global power is having on nations and people’s lives.

Special correspondent Baloch reported from Rawalpindi and Islamabad. Times staff writers Su and Bengali reported from Beijing and Singapore, respectively.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.