Hall of Fame basketball coach John Thompson of Georgetown dies at 78

- Share via

John Thompson Jr., the crusading African American college basketball coach who inspired counterparts from all races while making Georgetown an iconic brand, died late Sunday evening. He was 78.

Details about Thompson’s death were not immediately known; the school announced his passing as part of a statement in which it did not provide any specifics.

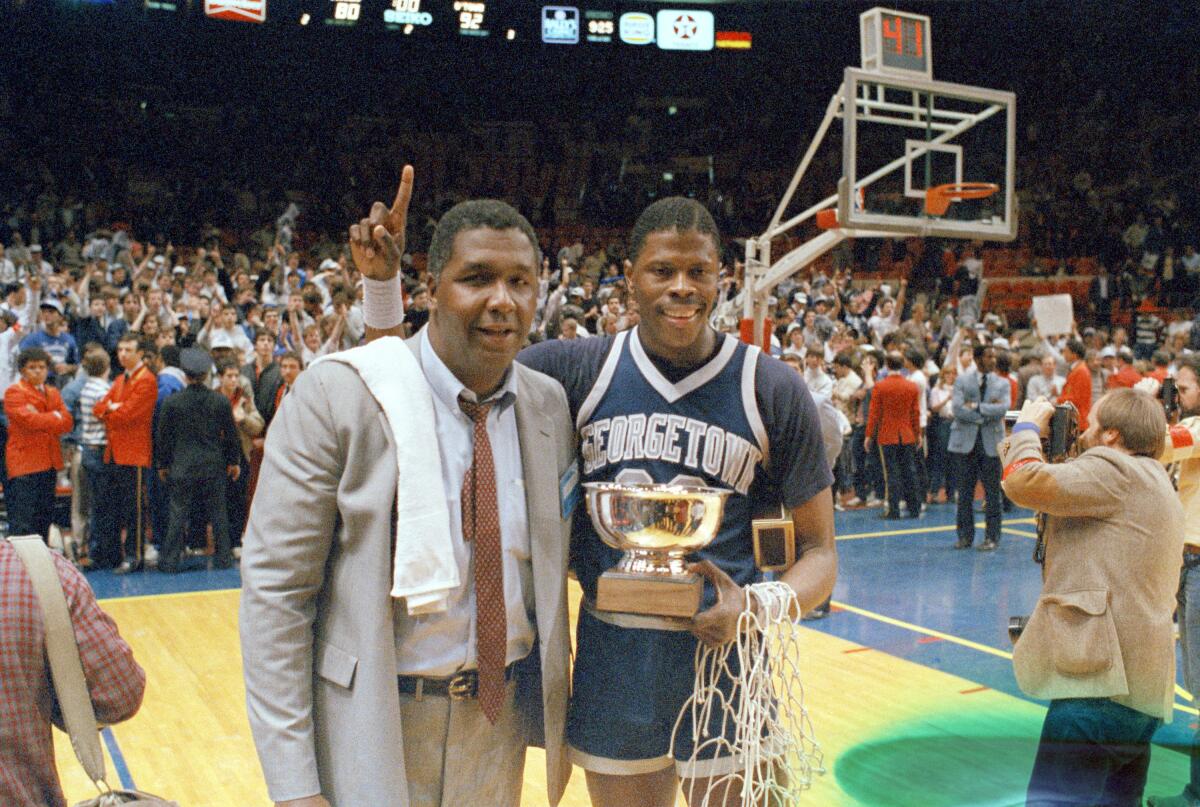

Asked upon his hiring at Georgetown to occasionally take the pitiful Hoyas to the National Invitation Tournament, a consolation prize for middling teams, Thompson instead built his team into a national power. The Hoyas went to three Final Fours and won the 1984 national title, making Thompson the first Black coach to win a major NCAA Division I basketball championship.

His teams also won seven Big East Conference regular-season titles and he directed the 1988 Olympic team to a bronze medal in the final Olympics before the United States began using NBA players and dominating the competition. Thompson finished his 27 college seasons — all at Georgetown — with a 596-239 record before being inducted into the Naismith Memorial and National College Basketball halls of fame.

“He was a true builder of young boys to men,” Clippers coach Doc Rivers wrote on Instagram. “Set the tone for us all. We will remember him as a coach. But anyone who came in contact realized, he was much more … a mountain of a man.”

A hulking presence at 6 feet 10 and roughly 300 pounds who walked unhurriedly, often with a folded white towel draped over the shoulder of his suit jacket, Thompson commanded attention with his stature and baritone voice. Some found it ironic that he was so successful at a largely white college with mostly Black players.

“What I think happened is that an intelligent Black man, with a clear idea of what he wanted, has weaved in and out between a lot of confused honkies and has accomplished things that have benefited both parties,” the Rev. Timothy S. Healy, Georgetown’s president, told Sports Illustrated in 1980.

Thompson was a relentless advocate for disadvantaged players, particularly from minority backgrounds. In what might have been his most powerful statement, he walked off the court before a game against Boston College in 1989 as part of a boycott to protest Proposition 48, an NCAA regulation that denied scholarships to players who failed to achieve minimum grades and standardized text scores.

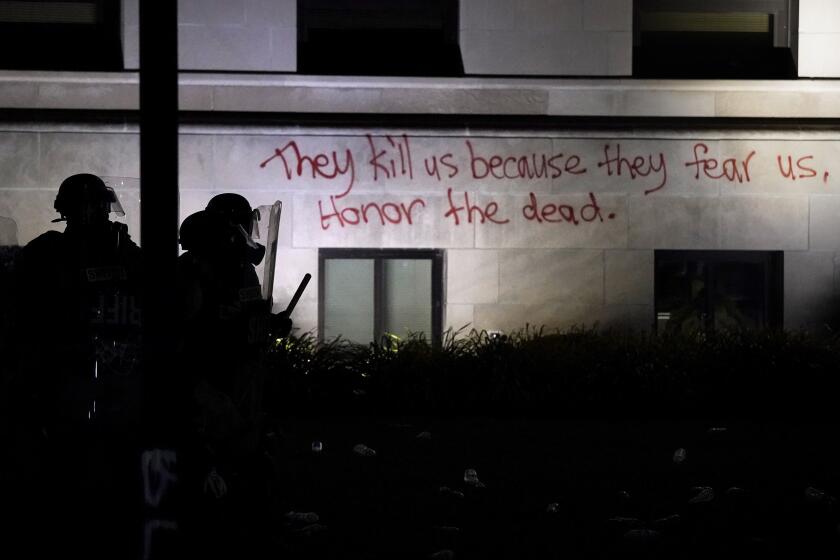

COVID-19 is a viral blip on the radar when it comes to systemic racism in America, which ignores warning signs, like Jacob Blake’s death, and denies it exists.

“I’ve done this because, out of frustration, you’re limited in your options of what you can do in response to something I felt was very wrong,” Thompson said. “This is my way of bringing attention to a rule a lot of people were not aware of — one which will affect a great many individuals. I did it to bring attention to the issue in hopes of getting [the NCAA] to take another look at what they’ve done, and if they feel it unjust, change the rule.”

When Thompson became the first Black coach to reach a Final Four in 1982, he said it meant that others before him were not given the same opportunity, college basketball author John Feinstein recalled in a 1999 interview on CNN.

“That was, clearly, an important point to make at a moment when he could have given an easy, cliché answer,” Feinstein said. “John Thompson never went for easy answers.”

Thompson was fiercely loyal to a legion of players that included eventual NBA stars Patrick Ewing, Allen Iverson, Dikembe Mutombo and Alonzo Mourning. Thompson continued to recruit Iverson after the prep prospect had spent four months in jail for allegedly participating in a brawl at a bowling alley before his senior year of high school. Iverson’s conviction eventually was overturned because of insufficient evidence and he went on to become the Big East rookie of the year and led the Hoyas to an NCAA tournament regional final as a sophomore.

“Thanks For Saving My Life Coach,” Iverson tweeted. “I’m going to miss you, but I’m sure that you are looking down on us with a big smile. I would give anything just for one more phone call from you only to hear you say, ‘Hey MF,’ then we would talk about everything except basketball……”

Born on Sept. 2, 1941, in a racially segregated nook of southeast Washington, D.C., Thompson developed an early aptitude for basketball that led to an All-American career as a center at Archbishop Carroll High. Later, at Providence College, he was captain of the first team in school history to reach the NCAA tournament, in 1964.

The Boston Celtics selected Thompson in the third round of that year’s NBA draft and he was a backup to Bill Russell on championship teams in each of his first two seasons. But he wouldn’t play another minute, surrendering to a more powerful lure: teaching kids to play the game he loved.

Thompson took a coaching job at St. Anthony Catholic School in Washington, his 122-28 record over six seasons emboldening him to apply for a vacancy at the sleepy college program in town. When Georgetown’s president at the time, the Rev. Robert J. Henle, told Thompson about his modest expectations upon the coach’s 1972 hiring that involved making the NIT “every now and then,” Thompson remained quiet.

“I thought to myself that I’d eat my hat if I couldn’t do better than that,” Thompson once told SI while recalling the exchange, “but I didn’t say anything except, ‘Yes, sir, I’ll try,’ because you don’t want to set yourself up.”

The new college coach had set himself up only for success. The Hoyas reached the NCAA tournament in 1975, ending a 32-year absence, and were routinely a player on the national stage by the time they joined the Big East in 1979.

Thompson’s teams won at least 20 games in 18 of his final 21 seasons before he resigned midway through the 1998-99 season, citing marital problems. He never coached again but continued his advocacy work, establishing The John Thompson Charitable Foundation to help improve the quality of life for underserved children.

His legacy continued to be felt on the Georgetown sideline, where his coaching successors included longtime assistant Craig Escherick, son John Thompson III and Ewing, who remains the Hoyas’ coach. The younger Thompson guided Georgetown back to the Final Four in 2007.

Thompson is survived by children John, Ronny and Tiffany and his five grandchildren. Memorial services are pending.

“We know that he will be deeply missed by many and our family appreciates your condolences and prayers,” the family said in a statement released by the school. “But don’t worry about him, because as he always liked to say, ‘Big Ace is cool.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.