- Share via

SIOUX FALLS, S.D. — In all his years walking into homes with a little white bottle of holy water, the Rev. Kristopher Cowles had never received a request like the recent one when a parishioner led him to a basement and pointed to a bed near a poster of the Virgin Mary and a carton of Clorox wipes.

“Can you bless our quarantine room?” said Ciriaco Barrera, a 64-year-old pork worker who secluded himself in the spot earlier this year only to see the disease take hold of his wife and daughter. “We can’t let it get us again.”

Cowles whispered a prayer and made the sign of the cross. He walked upstairs back into the light. He said goodbye to Barrera and drove through a city — like countless others across this land — that endured what even the faithful found almost impossible to bear.

The Smithfield hog processing plant where Barrera works sorting pigs for slaughter remains home to one of the worst single workplace outbreaks of COVID-19 in the nation. Two deaths and more than 900 infections in the spring led to a weeks-long closure, a backlog on pig farms, and a crippling fear among the thousands of immigrants and war refugees from dozens of countries who dominate the workforce.

Through it all, Our Lady of Guadalupe and its husky pastor, who’s partial to the Gospel of John and composes homilies on the fly, have stayed resilient in a small, dimly lit brick church with a bright turquoise ceiling northeast of downtown. The only Catholic Latino congregation in this half of South Dakota, a third of its parishioners are plant workers; the others have jobs cleaning hospitals and hotels or in construction and restaurants.

Most have gotten sick or know someone who has.

Cowles has knelt in their living rooms and stood on their porches. He has heard their sins and eased their burdens. He has his struggles, too, taking medication to battle depression and anxiety that would otherwise flare up during the darkest days of the last months. But congregant and preacher are joined by devotion and pain, and by what the virus has taught them about themselves and their city, which, like much of the country, is desperate to reclaim what it was before the disease landed here last winter.

Cowles led the funeral for a community member who died, and anointed another last month who recovered from the virus only to die of stomach cancer. He lit prayer candles when his secretary went into isolation as her parents became ill. For much of the flock, home visits, Facebook Live videos and phone calls replace Mass at the now half-empty church, where rope blocks every other pew and hymnals are stacked away.

“We used to run out of space for everyone who wanted to come before the coronavirus tore through,” said Cowles, a 36-year-old with an overgrown buzz cut and thick red beard that is barely covered by his black mask. “Now, I don’t know when they will all be back.”

“So I go to them.”

Sioux Falls, the state’s biggest city, where Smithfield is among the biggest employers, appears in many ways to have moved beyond the virus.

Maskless bachelorettes jam downtown bars on Phillips Avenue on muggy weekends. Indoor rodeos, minor league baseball and high school wrestling tournaments pack the summer season. New cases grow each day alongside statewide flare-ups, like a recent cluster that shut down a Christian summer camp by Mt. Rushmore that had ties to a Sioux Falls church. Still, the city boasts of consecutive days with zero deaths even as the virus surges in most corners of the nation.

Fewer workers call in sick now at Smithfield, where temperature checks, masks and face shields became the norm after it joined dozens of meat factories in shutting down. A high school parking lot test site for workers has closed and the corporation, under investigation by the federal government, has released only limited data on the virus at its properties. The company recently ran full-page ads in newspapers across the country, including The Times, criticizing “inaccurate media reports” about its handling of outbreaks and praising the “unsung heroes” it employs.

Yet for those reporting to the killing and processing floors on North Weber Avenue, the threat is real.

It’s a lurking, unwelcome guest who this community of new Americans, many of them Latino immigrants and others Asian and African refugees, pray never returns.

“Our Lady will protect us,” said Barrera, who spent six days a week at the factory and ran a 102-degree temperature in March before he was bedridden for a month.

He had worked in Department 1 at the plant for 18 years since moving his family from outside Fresno, where he and his wife picked cantaloupes and tomatoes after emigrating from San Salvador. A nephew who lived in town told them about the factory, where jobs paying double the minimum wage were plentiful in a place with affordable houses and cheap gas.

Maria Barrera, who worked in Department 26 slicing the fat from carcasses, followed her husband with her own fever. Her cough lasted through May. Their 18-year-old daughter, Daisy, tested positive but quickly recovered.

Ciriaco and Maria are back to work, though some coworkers aren’t. Ciriaco, who lost most of his Saturday overtime, said “two people do the work of three” in his department now.

“I’d rather this whole thing just be over,” he said as he peeled off his mask after genuflecting toward the tabernacle, passing Cowles and walking out of church on a recent Sunday.

Since it was built in 1926, just 17 years after the factory that now spreads over 45 acres northeast of downtown, Our Lady of Guadalupe has been a parish of factory workers.

Back then, the slaughterhouse was called John Morrell and the employees were white men. Today, it’s Smithfield, a Chinese-owned, Virginia-based company that produced 5% of the nation’s pork before the virus sent output plummeting. Its employees speak 80 languages and make up a large slice of the minority population in Sioux Falls, a city of 188,000 where 82% of people are white.

The church started off as St. Therese, a name it held until 1996, after Guatemalan, Salvadoran and Mexican immigrants began arriving by the thousands in Sioux Falls. Many came from California as they sought cheaper rents and union wages at Smithfield.

The parish is today named after the 16th century apparition in what is now Mexico City of a dark-skinned Virgin Mary. The global church’s patroness of the Americas, she is revered by Catholics across borders. Most congregants are Latino, and Mass, once only in English, is now largely in Spanish.

Cowles has led the church for six years after seminary in St. Paul, Minn., a short assignment in the state capital of Pierre and two months training with priests in Guadalajara. A native South Dakotan who was raised in Yankton by the Missouri River on the Nebraska border, he sticks out not only by his vestments, but with his pale white skin.

He travels around town in an old Toyota Highlander. When he gets days off, Cowles, a former Eagle Scout, camps in the Black Hills National Forest. He collects Batman comics and prizes a beaten up brass and gold chalice gifted to him by the Knights of Columbus, a fraternity of Catholic men. He calls himself a nerd and notes that he has memorized parts of “The Lord of the Rings.”

Cowles is fluent in Spanish, but he’s still learning new words and speaks with a thick American accent. Parishioners poke fun at him for the time years ago when he confused the words “servicio” and “cerveza” while preaching. In a part of the country with few Latino priests that are native speakers, he is forgiven his shortcomings. Cowles long ago stopped typing first drafts of homilies into Google Translate; he now delivers them in a kind of spiritual improvisation.

Many these days give a nod to the virus, though often not by name.

“Beside the presence of God,” Cowles said recently, “that is the one stable thing we have.”

Of the nine Catholic churches in Sioux Falls, the coronavirus has rearranged life at Our Lady of Guadalupe in ways unknown at others. Like elsewhere in the nation, the virus has disproportionately hit Latinos in this community, although they make up 5% of the city’s population.

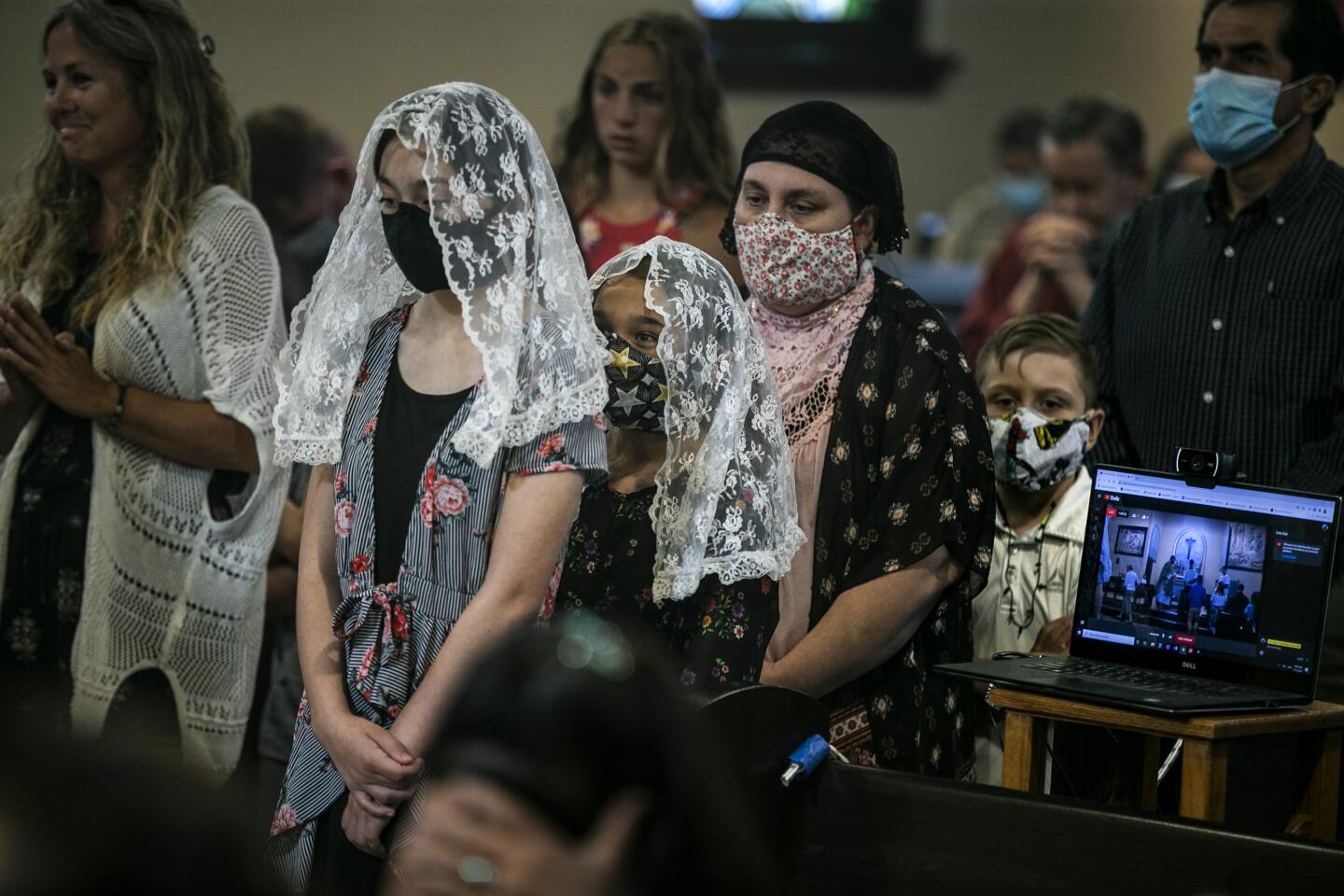

Some parishes are now packed on weekends, with no ropes cutting off pews. But Mass on Sunday evenings at Our Lady, where Cowles reminds spaced-apart families to spray and wipe their seats before leaving, might draw a few dozen people at most. Like he did in the early days of the pandemic, Cowles still sets up his iPhone on a tripod at Mass to broadcast on Facebook to those who stay home.

The priest has stopped wearing a mask at most services; some parishioners still do. He keeps a pump bottle of hand sanitizer next to the altar, in case he accidentally touches someone’s mouth as they kneel to receive Communion on their tongue.

Summer is usually packed with quinceañera Masses; he’s only had one small one so far this year. Some scoffed when he said recently that only immediate family could come to first communions. He offers pre-marriage counseling but has no ceremonies scheduled until 2021.

He tells parishioners to have “patience,” offering his own example of knowing the pain of being unable to pray with his mother. For months, Cowles could only see her through a closed window at her nursing home. Now they visit on a patio, wearing masks and sitting behind nets that keep them 10 feet apart. They shout to hear each other, and end their reunions with air hugs.

“Church is open. And we’re not open,” Cowles said, noting that his bishop hasn’t reinstated the religious obligation to attend in person. “We have to respect those who want to come in. And those who don’t.”

The Barreras returned to Our Lady together in June.

When the building wasn’t open for Mass, Ciriaco would stop by alone for adoration, where the Eucharist would be exposed each night for silent prayer. He would light candles for the family at a niche in front of a print of Our Lady in her turquoise tilma. Maria, whose lingering cough and pulmonary hypertension kept her away longer, now won’t go in the building without her disposable mask.

“I believe it was the prayers in church while I was gone that healed me,” said Maria, 50, on a recent Sunday. “I’m happy not being sick. But I’m happier being back in church.”

Ana Paulina Magaña, the parish secretary, is in the pews again, though her absence was shorter. The virus infected her parents, cousin and cousin’s husband — a Smithfield worker — earlier this year, and Magaña locked herself in at home with her nieces and brother for weeks.

“I never got sick but I know because of my family I can,” said Magaña, 36. Church is one of the few places she tolerates being in big groups without a mask. “I avoid Walmart because it has too many people.”

Esmeralda Rivas, whose family has gone to the parish for 12 years after moving from Washington state, is also back at Mass with her five kids and husband, who works in Department 8 slicing pork ribs. He dodged the sickness, though nearly everyone he ate lunch with in the break room wasn’t as lucky, and a worker the next department over died.

“God, watch over us all,” said Rivas, 39, who believes it was a force bigger than her that spared her family.

As life returns to a new version of normal, Cowles has fielded applications to the diocese’s relief fund, which took calls weekly for help from those who were sick or had lost jobs. The church has written dozens of $500 checks to cover rent and medical bills, making up a small part of unemployment pay that applicants, many of them undocumented immigrants, can’t get. Most were non-Catholics or churchgoers from outside his parish.

But on occasion, he’s seen familiar names among those needing help that listed the same workplace: Smithfield.

Times staff writer Julia Barajas contributed to this report.

(This is the second in a series of occasional stories on the coronavirus’ effect on the Sioux Falls Smithfield plant and its workers.)

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.