At Talladega, NASCAR fans reckon with a noose found in Bubba Wallace’s garage stall

- Share via

LINCOLN, Alabama — A large crowd of NASCAR drivers and pit crew members walked behind Darrell “Bubba” Wallace Jr. in his No. 43 car Monday on their way to the front of the field before the NASCAR Cup Series GEICO 500 race at the Talladega Superspeedway.

After his Chevrolet Camaro came to a stop, Wallace climbed out and sobbed.

With thousands of NASCAR fans looking on, Richard Petty, the Hall of Fame NASCAR driver who was among Wallace’s many supporters, placed a hand on his shoulder.

A day earlier, a noose was found hanging in Wallace’s garage stall at the racetrack. Wallace, who is Black, had recently called for NASCAR to ban Confederate flags at its races, which the organization did at all its properties.

Wallace, 26, in recent weeks has driven a car decked out in Black Lives Matter livery. He denounced the hanging of the noose as a “despicable act of racism and hatred” that served as a “painful reminder of how much further we have to go as a society.”

“As my mother told me today, ‘They are just trying to scare you,’” Wallace said in a statement on Twitter. “This will not break me, I will not give in nor will I back down. I will continue to proudly stand for what I believe in.”

NASCAR responded to a noose in Bubba Wallace’s garage with a show of support for its only Black driver, but its fight remains with the Confederate flag, columnist LZ Granderson writes.

NASCAR President Steve Phelps said the stock-racing organization contacted the FBI on Monday after a member of Wallace’s team reported discovering the noose Sunday afternoon in Wallace’s garage stall. NASCAR, he said, would permanently ban whoever hung the noose.

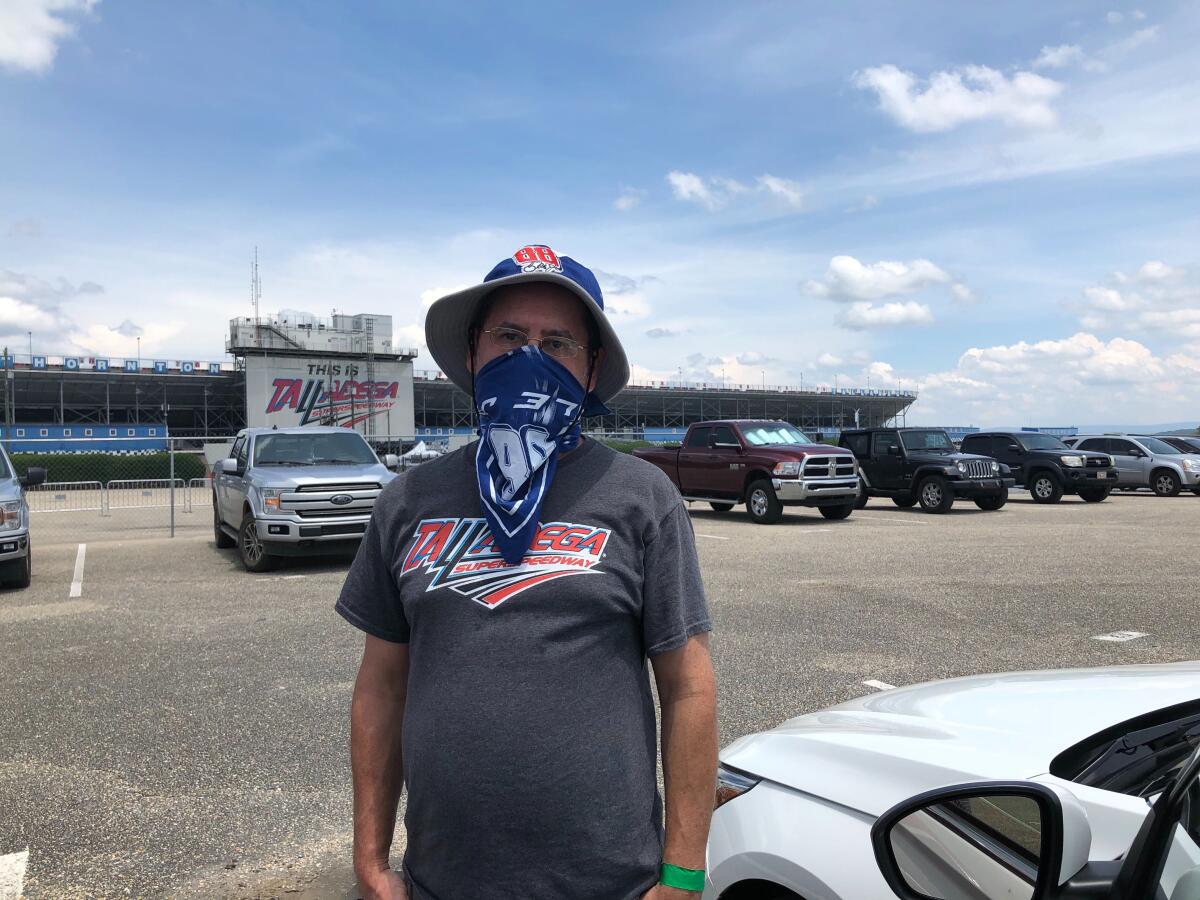

Many fans at the stadium Monday said they were surprised that anyone would hang a noose in Wallace’s garage. Although opinion was divided on the banning of the flag, many people said the noose was too much.

Frankie Bailey, 60, from the nearby town of Sylacauga, said he did not know what to make of the noose.

“How did it get there?” he said.

As fans streamed into the Superspeedway on Monday, a few stopped to park their sedans and pickup trucks on the side of the four-lane highway and browse a row of vendor tents selling Confederate flags, Trump 2020 flags and NASCAR paraphernalia.

Sean Ramirez, a 54-year-old vendor from Pensacola, Fla., said his business had tripled over the last week after NASCAR’s decision to ban the flag from its grounds.

Many of his customers saw defending the flag as protecting their heritage.

“It’s history,” he shrugged. “You can’t change history. … You can’t erase history.”

Defiance seemed more subdued Monday than Sunday, when a convoy of cars and pickup trucks paraded the Confederate flag past the entrance to the Superspeedway and a small plane flew over the racetrack trailing a banner with a flag that said “Defund NASCAR.”

“I’m kind of lost for words,” Jason Solis, 54, from Nashville, Tenn., said as he sat in the parking lot before the race, contemplating why anyone would hang a noose.

“I think sometimes people just look for a reason to be mad,” he said. “You know, people are saying they’re not going to watch the race because of the flag. ... I think their love for the sport doesn’t run that deep if they feel that.”

Solis said that in high school he wore a T-shirt with a Confederate flag. When he was 19, he had a ’72 Chevelle Super Sport with a Confederate flag license tag — until two black coworkers called him out.

“That was in the early or mid 1980s,” he said. “I took it off after they said that. … As I’ve gotten older, I can really see how it hurts.”

This was not the first time NASCAR had attempted to purge the Confederate flag from its tracks and grounds. Five years ago, former Chairman Brian France attempted to ban flying the flags at tracks, but his proposal was widely ignored.

Over the last month, the organization faced pressure from Wallace as protests erupted across the nation in response to the killing of George Floyd and police brutality. In recent weeks, Wallace has worn a black T-shirt with the words “I Can’t Breathe” and has had his livery painted with #BlackLivesMatter.

On Monday, NASCAR announced it had launched an investigation to identify the person responsible for the noose and “eliminate them” from the sport.

“We are angry and outraged, and cannot state strongly enough how seriously we take this heinous act,” NASCAR said in a statement. “As we have stated unequivocally, there is no place for racism in NASCAR, and this act only strengthens our resolve to make the sport open and welcoming to all.”

U.S. Attorney Jay Town said in a statement Monday that his office, the FBI and the Department of Justice Civil Rights Division were reviewing whether federal charges could be filed.

“Regardless of whether federal charges can be brought,” Town said, “this type of action has no place in our society.”

The owner of the NASCAR Village tent on Speedway Boulevard, who refused to give his name because he said he had received “hate calls” over the last 24 hours after being quoted in news reports, said, “People aren’t real happy about taking away the flag.”

His large white tent was mainly filled with NASCAR T-shirts, stickers and koozies, but he also featured a large Confederate battle flag and red T-shirt with a Confederate flag. His biggest sellers were Chase Elliott and Kevin Harvick T-shirts. Bubba Wallace, he said, was not a top-tier driver.

Still, some fans came in search of merchandise celebrating Wallace.

“You got anything for Bubba Wallace?” Joshua, 15, a white teenager, asked as he entered the tent.

Joshua, whose father declined to give the family’s last name after hearing the store owner say he had gotten hateful phone calls, said he was disappointed that someone had put a noose in Wallace’s garage. He called the incident “inappropriate.”

“It’s very racist,” he said of the noose as he picked up a Bubba koozie.

“The flag, I don’t fly it,” Joshua said. “It’s a cool flag, but I don’t support it.”

“It’s a part of history,” his dad said.

Joshua nodded. Taking it down, they agreed, wouldn’t change their experience of the race.

After the race, Patrick Everett, 35, a U.S. Army veteran from Pell City, Ala., said he felt sick when he heard a noose had been hung in Wallace’s garage.

“It’s just hateful,” he said.

All week, Everett felt disheartened as he heard people say they would not support NASCAR because it had banned the flag.

“To me, the Confederate flag is not the symbol some people want it to be,” he said. “Some of the real deep, deep Southerners want to say it’s about heritage. It’s more a symbol of hate. It’s so far in history, I feel like it belongs in a museum.”

Seeing all the drivers walk around the track Monday in solidarity with Wallace lifted Everett’s spirits and made him feel NASCAR could move beyond the division.

“It was awesome,” he said. “It made me cheer for Bubba.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.